Tucked away in the back room of Merritt College’s Microscopy Laboratory is a piece of machinery whose small stature belies its powerful capacity.

Housed in room D247, the laboratory is home to the tabletop TM3000 scanning electron microscope (SEM), which bears a striking resemblance to R2-D2’s kid brother, and its SwiftED3000 attachment.

On loan from manufacturer Hitachi, the TM3000 SEM was the focal point of a week-long event from April 21–25 designed to educate and inform the public of the benefit of acquiring a piece of research equipment which, according to laboratory technician Peter Werner, might one day make its way onto the International Space Station.

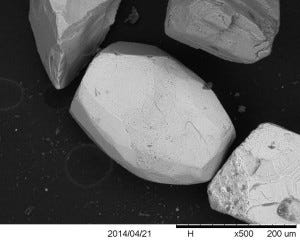

Werner explained that, unlike optical microscopes or cameras which use multiple focal points to zoom in on images or laboratory specimens, the TM3000 produces a single focal point. This is done by utilizing a tungsten metal filament, enclosed in a vacuum chamber, to project a beam of electrons onto a specimen. The TM3000, therefore, is capable of magnification of up to 30,000 times.

Furthermore, according to Werner, the low vacuum of the TM3000 creates certain advantages which the more powerful, floor-model SEM’s do not. High vacuum electron microscopes generally produce a “charge-up” phenomenon, where electrons accumulate on the surface of fresh biological specimens.

This “charge-up” can actually destroy such specimens, which requires researchers to engage in a labor-intensive process by which the specimens are cryo-frozen and then coated in some type of metal in order to effectively view them.

Because the TM3000 uses a low vacuum, fresh biological specimens such as a half-eaten cricket (leftovers from a meal fed to a student’s pet lizard) can be viewed without any such special preparation, as Werner demonstrated to this reporter.

Further uses include elemental analysis of specimens, made possible by the TM3000’s SwiftED3000 attachment. Laney student Jon Howell, who was taking advantage of the open lab time, was present in order to examine samples of sand collected from a beach in Cuba.

Howell explained that he was assisting College of Alameda chemistry Professor Peter Olds in possibly proving an interesting hypothesis: that the asteroid strike which caused the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs may need revision.

The mass extinction event that rendered the dinosaurs extinct is currently thought to have been caused by a single asteroid strike near the Yucatan Peninsula in an area known as the “Chicxulub Crater.”

Evidence for this asteroid strike is cited as the presence of chromium in the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K-Pg) stratum of the Earth’s soil.

Howell was analyzing the Cuban sand grains for chromium content, which could prove their extraterrestrial origin.

Given their presence so much further out into the Caribbean Sea, this could be evidence of a binary meteorite strike — an event in which a second meteorite collided with the Earth at or near the same time as the one thought to have caused the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction.

Howell cited the TM3000’s ease of use, calling it “user-friendly,” and noted that if the SEM could be acquired on a permanent basis, which according to Werner could cost in the neighborhood of $150,000 for a new unit, it would widely improve research and learning opportunities for faculty and students alike.

Merritt Professor Hank Fabian of the Genomics Department, who was also briefly on hand, succinctly concurred. Speaking of the TM3000, Fabian said, “With options come opportunities for high-power jobs.”

Check out our new Galleries page for images from the last issues’ Photo Essay on the EMS.