Gabriela Abrego has lived in California for the last 31 years, more than half her life, renewing her green card every ten years. But on Aug. 20, she took the first decisive step toward becoming a U.S. citizen.

She was joined by 180 others in the Laney College Student Center for the naturalization workshop put on by the volunteer attorneys of APILO (Asian and Pacific Islanders Legal Outreach).

After 31 years, why now?

“My father passed away two months ago and I went home to Mexico City,” Abrego said.

“When I came back the immigration lady, she noticed my green card expired in January, and she said why don’t you apply to be an American citizen? And I said I think now is a good time.”  With her father gone now Abrego worries about her mother living alone. “Now she is okay, healthy and normal,” she said, “but you know…”

With her father gone now Abrego worries about her mother living alone. “Now she is okay, healthy and normal,” she said, “but you know…”

And once Abrego is a citizen, when she goes back to Mexico to check on her mom, she won’t have to worry about overstaying her six-month limit.

And then there is the matter of fees. “Instead of paying for another green card I can pay the [$680] application fee for citizenship,” Abrego said.

Money is a persistent problem.

“When I have the money I don’t have time to be an American citizen; when I have time I don’t have the money. Right now, it is time.”

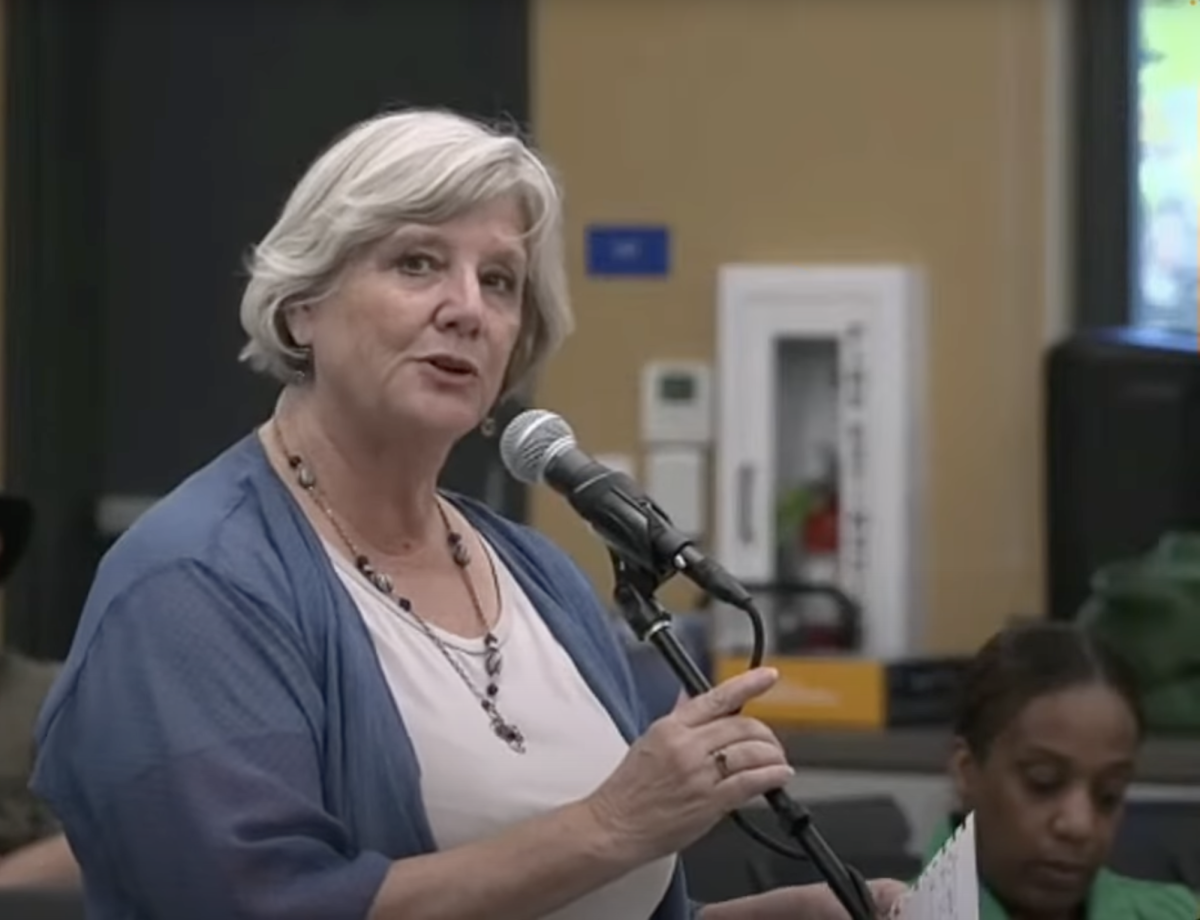

The workshop is arranged in seven stations, each one staffed by a volunteer who helps the applicant navigate through the next step of the application process. Station Three is staffed by experienced immigration attorneys.  After the applicants go through all the seven stations one of the attorneys does a final checkout to make sure they have all the materials they need.

After the applicants go through all the seven stations one of the attorneys does a final checkout to make sure they have all the materials they need.

Some applicants have preregistered and done all the homework asked of them. They can send their applications to the Immigration Service. Others will have outstanding tasks yet to do. At Station Seven are fliers announcing free ESL and citizenship classes.

Becoming a naturalized citizen is a long and complex process.

Step one: Passing through the seven stations of the Aug. 20 workshop was part of the first step, getting the paperwork together and sending it in, along with the $680 filing fee.

Step two: The Immigration Service contacts the applicant to get “biometrics” (fingerprints and a laser-assisted photograph). The biometric data goes directly into their database together with an FBI background check to rule out a criminal history.

Step three: The Immigration Service contacts the applicant by mail with a interview time and date. “Everybody stresses over ‘the test’”, Wong noted. The interviews are done orally, which makes it difficult for those with a shaky grasp of English and for anyone who is anxious. Once they’ve passed that step, they go on to take the oath of allegiance.

Step four: The oath of allegiance ceremonies take place here in Oakland at the Paramount Theater. Wong lights up as she describes the scene. “You see how rich the Bay Area is in diversity.

“Last one I went to over 75 countries were represented in the 1200 people who were taking their oaths. It’s exciting. They get to bring their families, and it’s a really happy moment for them.”

Wong began as a volunteer with APILO five years ago. Doing this work is her way of giving back, she explains, and then she gives me a brief history of Chinese immigration.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882 and was not repealed until 1948.

It was a specific law that excluded all Chinese people from immigrating to the U.S.

“Just like a certain presidential candidate wants to do with Muslims. It’s really offensive to me,” she says. “Because Chinese have also borne the brunt of that — we don’t need to go backwards — we need to go forward.”  Even after the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed it was still difficult for Chinese immigrants to come to the U.S. until there were opportunities for Chinese refugees fleeing communism.

Even after the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed it was still difficult for Chinese immigrants to come to the U.S. until there were opportunities for Chinese refugees fleeing communism.

Still, certain countries were favored in getting visas and immigration remained Eurocentric. “Chinese immigration didn’t really explode until the early Sixties,” Wong explained. “Until President Kennedy changed that and made it more equal.”

Becoming a citizen changes lives in dramatic ways. U.S. citizens can apply for jobs that only hire citizens. They can serve on a jury. They can vote, they can become civically engaged to help their communities and families.

They can travel back to their home countries and not have to return in six months or risk losing their legal resident status. And as U.S. citizens they can be legal sponsors for their relatives back home and bring their family members to the U.S.

English fluency is a requirement to become a citizen. “Sometimes we get people who have zero English,“ says Wong. “We don’t want to discourage them, we definitely want to encourage them in the process, but we have to warn them that they do have to have a certain level of English fluency by the time they get to their test [and interview].”

Wong represents people who have complications in their naturalization cases, many of them elderly and suffering from dementia. That prevents them from learning a new language or American history and civics, all required. So she helps these elderly clients apply for disability waivers.

Wong made a point of inviting students from the Peralta Colleges to participate, either as volunteers or as clients. Information about upcoming workshops and the process of becoming a citizen can be found on their website: www.ebnatz.org

This story is part of a feature named “A nation of immigrants, a journey to citizenship”.