Oakland exhibit traces history of Black Panthers Party

Oakland, fifty years ago: two visionary students at Merritt College joined together and started a revolutionary organization.

These students were Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. They called their organization the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, and they fought militantly, at times controversially, for the civil rights of minorities.

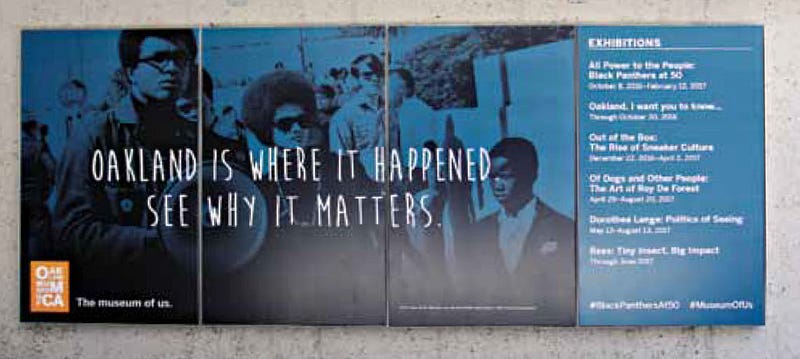

From now until Feb. 12, 2017, the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) honors the legacy of this bold movement created in 1966 with their exhibit, “All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50.”

MANY HISTORIES

There are many tributes being paid to the Black Panther Party movement to coincide with its 50th anniversary.

Merritt College will host a week-long series of events, starting with a film screening of the documentary, “Merritt College: Home of the Black Panther Party,” on Oct.18.

OMCA offers visitors the chance to understand the party as it existed in its active years, as well as the impact it has had beyond those years.

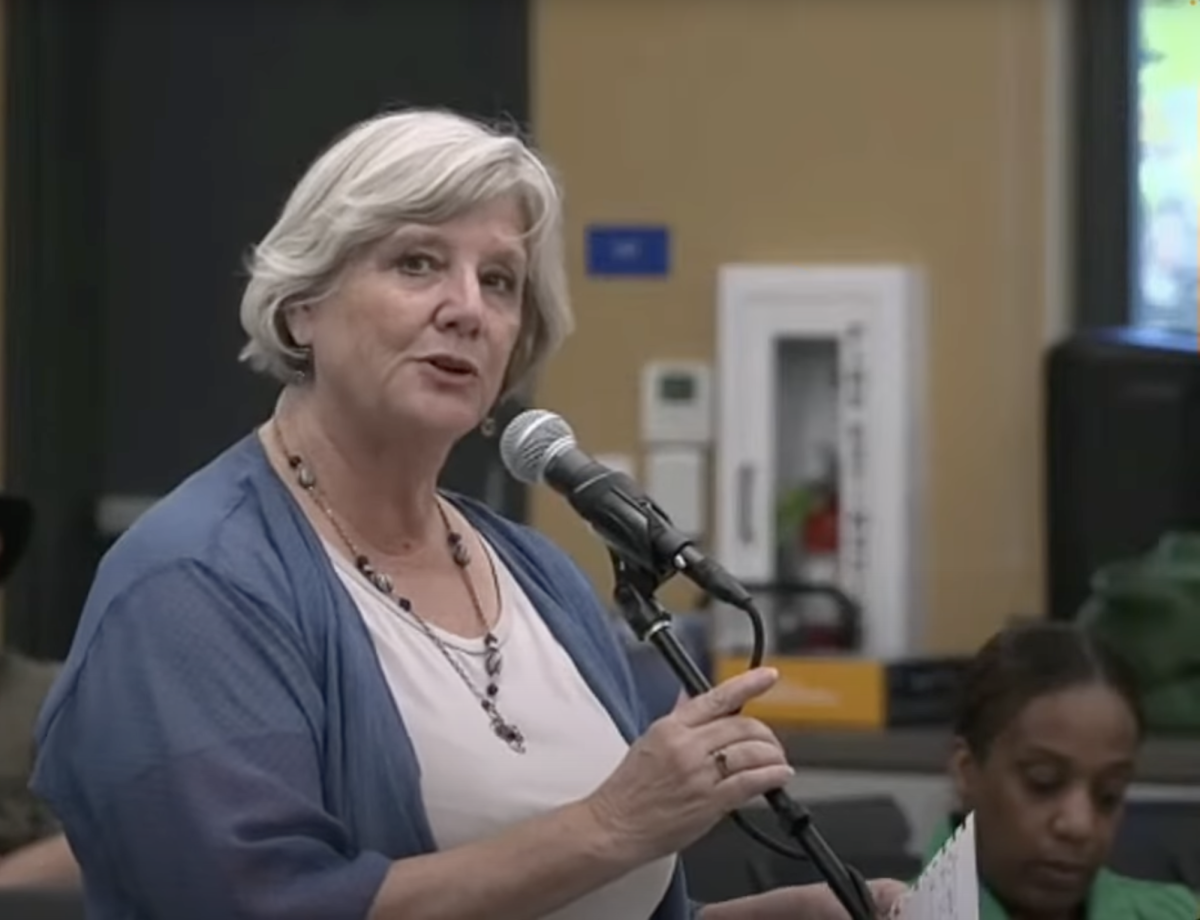

“What you will find in here is the lifespan of the Black Panthers at 50,” Lori Fogarty, director of the museum, said.

“The Black Panthers are a deeply local story that’s had lasting national and international influence,” René de Guzman, OMCA senior curator of art and director of exhibition strategy, said.

“It’s a truly compelling story that deserves a place in American history,” he added, standing just feet away from Sam Durant’s “Proposal for a Monument to Huey P. Newton for the Alameda County Courthouse,” a bronze replica of the wicker chair which hosts Newton in the historic photograph by Blair Stapp, also on display.

The Black Panthers Party’s commitment to social justice for Black lives has paved the way for today’s socio-political activist organizations. “Over time, the Black Panthers have become even more relevant today,” de Guzman said, “The gravity of the Black Lives Matter movement paralleled our development, and of course, as we’re experiencing now in the presidential election, [so did] the serious conversation

around race and equity.”

A press release by the OMCA states that the exhibit shows “aspects of the Party that are not often told.” These aspects offer insight into the inner workings of the party, their goals, and the level of organization with which they operated.

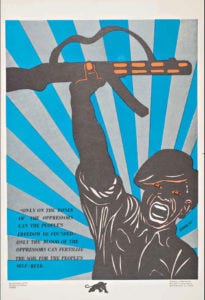

The Panthers were more than anger, afros, and ammo. The many violent clashes between police and Panthers aroused more attention than the work they were doing to help their communities.

They created community service programs like the Free Breakfast for School Children Program which spread across the nation and at its peak served 20,000 school-aged children full free breakfasts every day, according to a story on National Geographic’s website by Andrea King Collier in Nov. 2015.

NEVER BEFORE SEEN

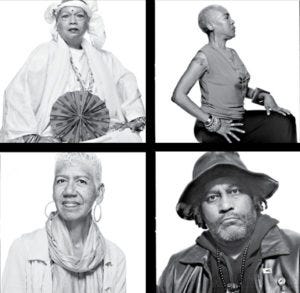

“All Power to the People” includes never-before-seen documentaries and photos, interviews with former Panthers, as well as “rare artifacts like a handwritten draft of the Ten Point Program from 1967 andan audio recording of Bobby Seale sharing his thoughts and the conditions related to the Program’s

creation.” The exhibit also includes works which represent the narratives of the generations since, including actual children of Party members.

David Huffman, son of Dolores Huffman, who designed much of the historic imagery used by the party, said, ”I held picket signs when I was 5, and it’s funny because the courthouse next door was where we did a lot of our protesting, you know, Free Huey. ”

His mother designed the iconic Free Huey flag, as well as the panther profile which she screenprinted onto dashikis and dresses.

David Huffman is now a notable Afrofuturist painter and installation artist. Two of the paintings from his Traumanaut series are on display at “All Power to the People.”

This series depicts black faces inside space suits which have a strange luminosity due to the special blend of materials Huffman used to create a blacklight effect.

His painting, “MLK,” is a portrait of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral procession. “I thought, you know what, I need a piece to kind of keep us in tune with the loss,” he said.

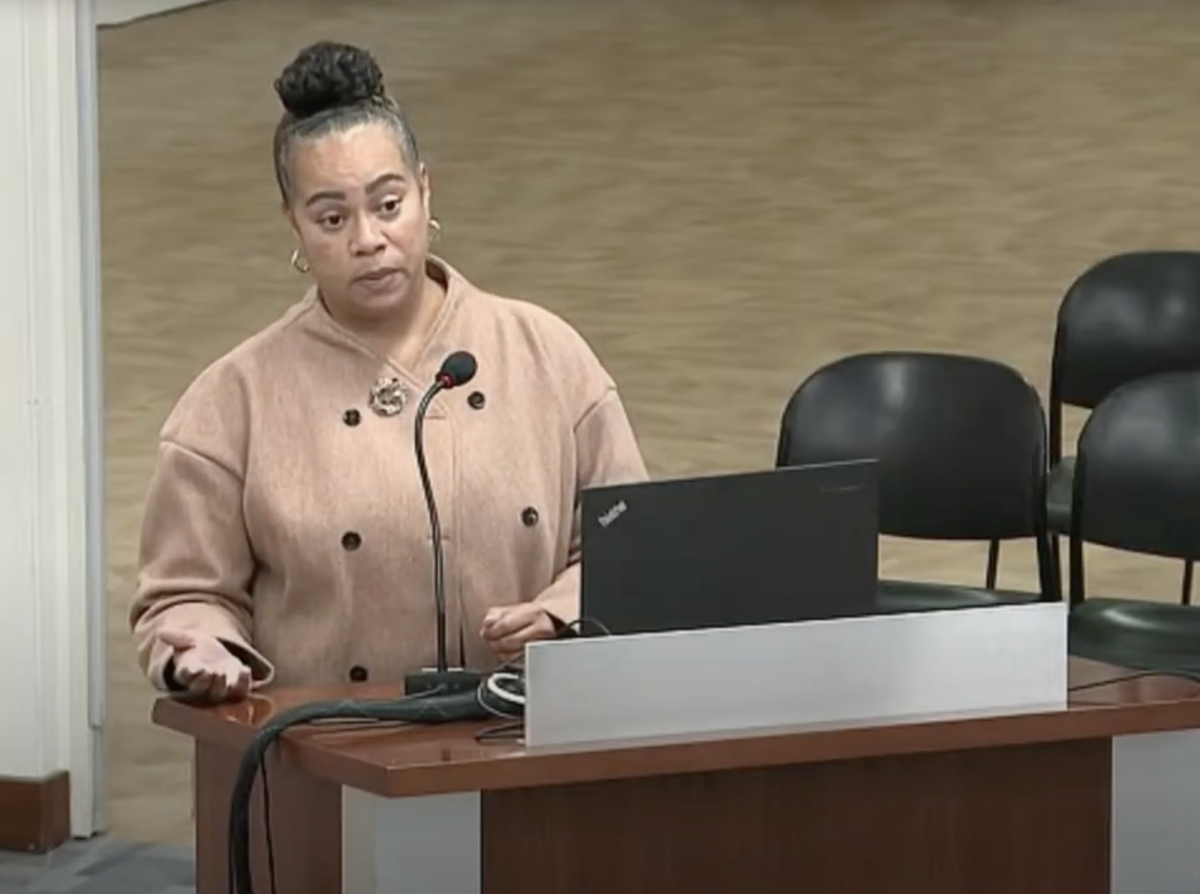

Sadie Barnette is the daughter of notable Panther Rodney Barnette, who started the Compton chapter. Through the Freedom of Information Act, Barnette was able to obtain her father’s FBI files.

“It took like four years of back-and-forth with the FBI, so it wasn’t exactly easy, but it is your right,” Barnette said.

After hearing about its upcoming Black Panther exhibit, she collaborated with OMCA to install these files as an art piece.

Barnette said she’s investigated her father before, but hadn’t displayed his FBI files.

“I felt like the [exhibit opening] was the perfect time to open up this project and see where it goes,” Barnette said.

The Black Panthers Ten-Point Program, published in May 1967

– We want freedom, power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

– We want full employment for our people.

– We want an end to the robbery by the CAPITALIST of our Black Community.

– We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

– We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society.

– We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society. We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

– We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

– We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

– We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

– We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

The Movement for Black Lives List of Demands, published in August 2016

– We demand an end to the war against Black people.

– We demand reparations for past and continuing harms.

– We demand investments in the education, health and safety of Black people, instead of investments in the criminalizing, caging, and harming of Black people.

– We demand economic justice for all and a reconstruction of the economy to ensure Black communities have collective ownership, not merely access.

– We demand a world where those most impacted in our communities control the laws, institutions, and policies that are meant to serve us — from our schools to our local budgets, economies, police departments, and our land — while recognizing that the rights and histories of our Indigenous family must also be respected.

– We demand independent Black political power and Black self-determination in all areas of society. We envision a remaking of the current U.S. political system in order to create a real democracy where Black people and all marginalized people can effectively exercise full political power.