Veteran journalists and media attorney teach students the power of CPRA

By Robert Hinton

Democracy works only when citizens can trust their elected officials. When politicians fail in the course of their duties, how can citizens act to ensure their will is observed and enacted?

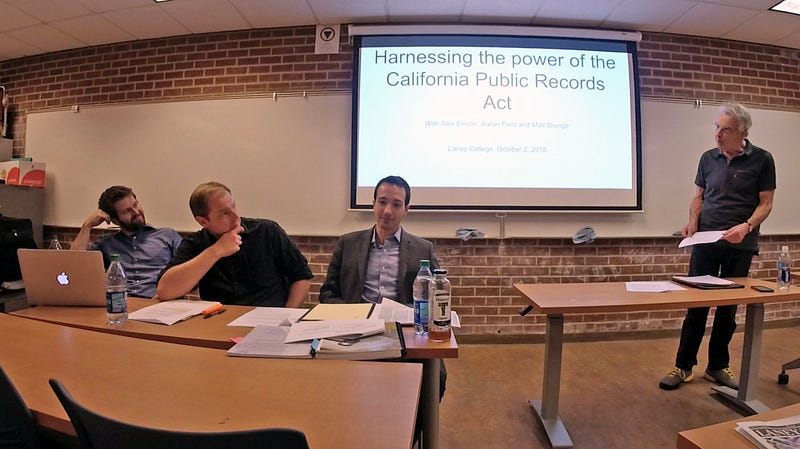

Journalists Matt Drange of The Information, Alex Emslie of KQED, and media law attorney Aaron Field made a presentation called “Harnessing the Power of the California Public Records Act” on Oct. 2 in F-203.

‘California identified that government transparency is important and essential to democracy’

Aaron Field

Media Law Attorney

Journalists Drange and Emslie use CPRA to uncover information in order to write in-depth investigative articles, and Field represents clients in a number of civil cases as well as First Amendment law.

Investigators, journalists and attorneys use CPRA in the course of their jobs, but anyone concerned about the behavior of officials and public institutions can use this legislative tool to better inform themselves about how government works in the Golden State.

Drange, Emslie, and Field educated the students about how CPRA works and how it can be utilized when investigating public officials and offices, as well as the specifics of how requests need to be filed in order to obtain information.

Signed into law in 1968, CPRA allows for the inspection or disclosure of government records by the public, unless exempted by law. Records that could be exempted are personnel, medical and initial drafts of memoranda.

“California identified that government transparency is important and essential to democracy,” Field said.

A public record is defined by the state of California’s website as “any writing containing information relating to the conduct of a public’s business prepared, owned, used or retained by any state or local agency regardless of physical form or characteristic.”

Police body-cam footage and even text messages from public officials’ phone records can be obtained under CPRA.

Requests for information should be made in writing. Initially, an investigator can make a phone call to the office they’re looking for information about. This approach preserves a civil relationship between the office and the requester in an attempt to ensure that information is shared in a timely manner.

“Push back at least once” if the congenial approach does not work, Emslie said. This shows that the request is serious and the information that is the public’s right to know must be delivered.

Any request for information must be responded to within 10 days of the request. If the information is not easily obtained, the office in question can request an additional 14 days in order to fully comply with the request.

There are many different tools and templates available online that can also help format your request so that inquiries are not held up because of paperwork issues.

The Student Press Law Center’s website was recommended by Drange as a resource to file free requests in any state. The SPLC will automatically create your request with the appropriate statutes on the document for the state you are requesting the information from.

‘Our goal is that you feel confident and enabled to file your request for whatever you want.’

Matt Drange

Journalist for ‘The Information’

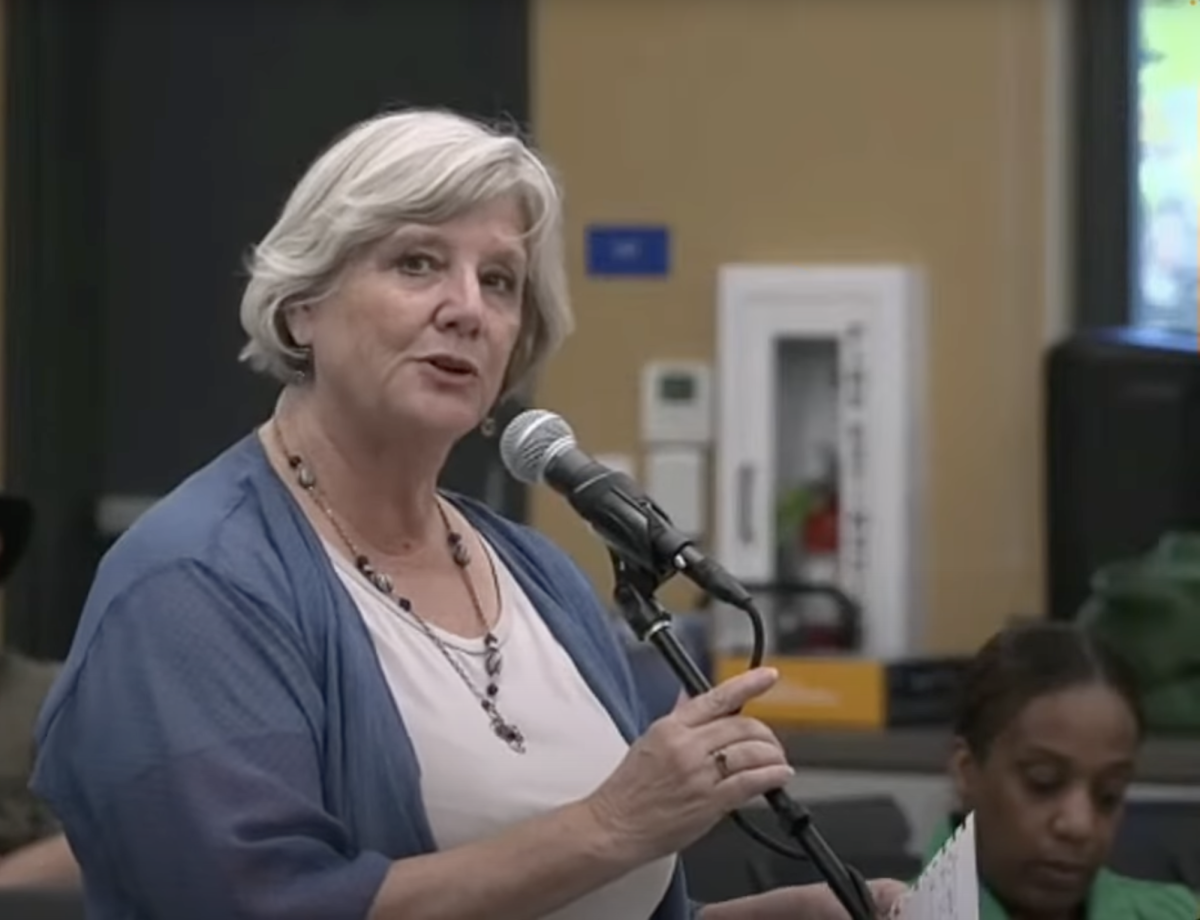

Laney Tower Editor-in-Chief Michelle Snider was the sole attendee that has experience using CPRA to seek further information on an incident that concerned her. Snider filmed the infamous “BBQ Becky” incident at Oakland’s Lake Merritt.

“I really wanted to know everything about her and what her interests were,” Snider said, referring to the woman in her video that called the police on two Black men barbecuing next to Lake Merritt.

“Reporters got [dispatch logs and statements] before me,” Snider said.

In the end, it took her months to actually get any information back from the Oakland Police Department about the incident she had filmed.

Thanks to the presentation by Drange, Emslie and Field, the Laney community is a little more informed of their rights. The information will help the Laney Tower accurately report on incidents that affect students and faculty.

“Our goal is that you’ll feel confident and enabled to file your request for whatever you want,” Drange said.