The Citizen renounces discrimination in all its forms and would like to provide our readers with a trigger warning for language that could be disturbing in the article below.

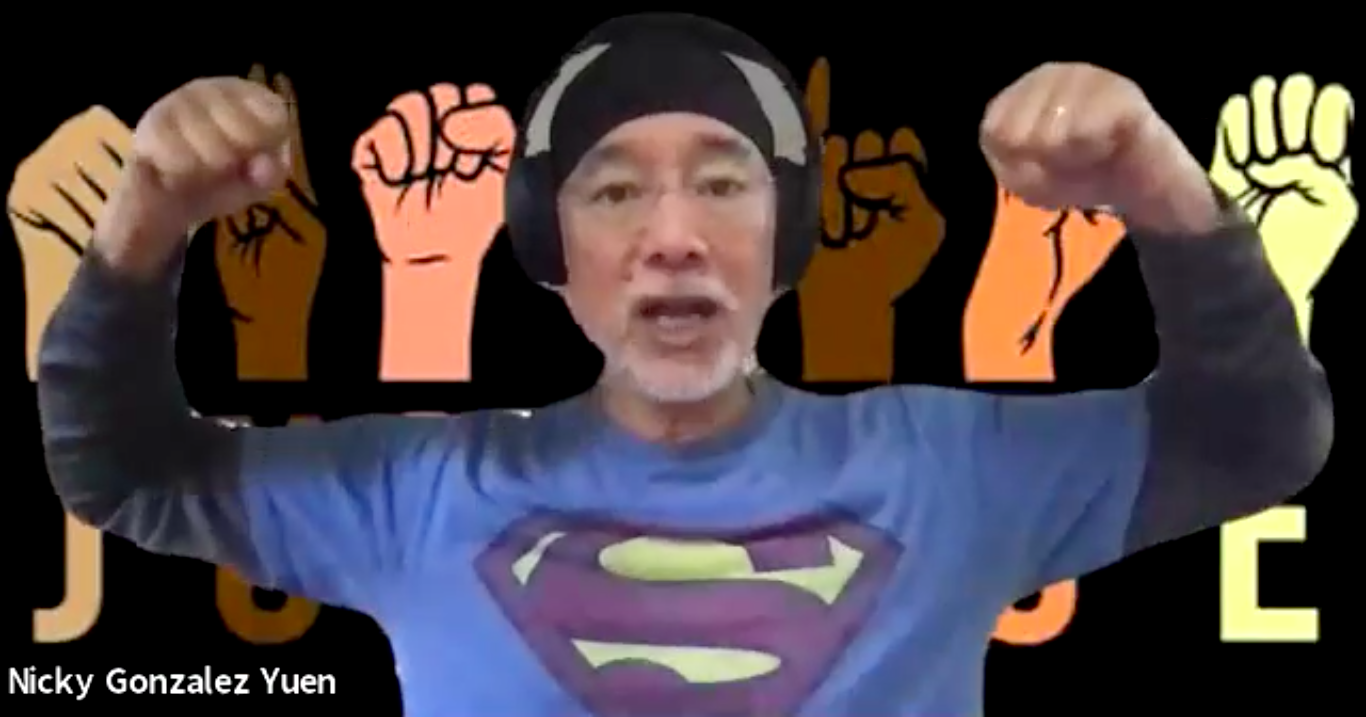

Nicky González Yuen zooms onto the screen wearing a purple Superman T-shirt. It’s late Saturday afternoon and he has just finished a meeting with his political science interns. González Yuen apologetically sets a time frame — he has another meeting to follow.

Nicky, as he prefers to be called, is affable, passionate about his work, and has a perpetual twinkle in his eye. His virtual Zoom background sums it up. It is not a sunset or a tropical beach, but a banner that reads “Justice” superimposed on raised fists of every skin tone. González Yuen is a teacher, union leader, scholar, author, mentor and a savvy political activist who stands with the disenfranchised when they need a champion.

Currently he is running unopposed in Area 4 for the Peralta Community College District Board of Trustees, a position he has held for 16 years.

In 2018 a fellow board member labeled him a “rogue trustee” and criticized him for being “too bossy.” González Yuen contended this was a free speech matter and he was warning of “widespread financial and managerial problems” at Peralta that the trustees and chancellor were “unable or unwilling to address.”

He was threatened with censure for speaking out about the significant financial concerns at Peralta that were later outlined in the 2019 Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team report.

During his time on the board, González Yuen has been a part of bringing environmental sustainability policies to Peralta and the adoption of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) building standards. He has made it his priority to advocate for job security for part time faculty and pay parity. He has advocated for greater power for student trustees on the board so they could be stronger advocates. Some might call him “rogue,” but others might call him feisty.

González Yuen teaches political science full time at De Anza college in Cupertino. “I view my primary job as training students for civic engagement through critical thinking and exposure to opportunities for them to engage in grassroots political action,” he said.

One such opportunity he has initiated is “Campus Camp Wellstone,” a De Anza organization that trains students to organize and mobilize for change.

To know Nicky’s history is to understand why he is so passionate about education, social justice, freedom of speech and civil rights. “Rogue” or not, he says it is in his blood to make “good trouble,” recalling a quote from the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis.

González Yuen’s parents immigrated to the US from the West Indies to “follow the wealth” and greater opportunity. His mother is Chinese and his father mostly European — Spanish, Scots, French and English, with a little African and Indigenous heritage “thrown in.” His father spoke with a British accent and identified as white. “But we weren’t white, no matter how white he was,” González Yuen clarified.

As a young child growing up in the deep south, Nicky learned about racism firsthand. His father, a psychiatrist, completed his residency in Louisiana, which was very segregated at the time.

“We were the only non-white children in this school and it was a fairly horrific experience,” González Yuen said.

As a young child of mixed heritage he was an “anomaly” — he was ostracized by his schoolmates who called him “ch*nk” and “dirty j*p.”

When he was eight years old, González Yuen’s family moved to southern California where his father’s name “González” identified him to others as “Mexican.” This only added to his confusion. His parents didn’t know how to talk to him about racism, and were unable to help him understand the behavior of the other children and the pain and confusion he felt. These early experiences contributed to his investment in multiculturalism.

When González Yuen was a preteen, his father abandoned the family and left his mother to raise six children without any financial support. She had been a homemaker all those years and had to figure a way to support her family. She tried business school, but after a month said, “I’m never going to be somebody’s secretary. I was somebody’s wife, and that was enough,” González Yuen recalled. His mother ultimately obtained a law degree from La Verne University.

Following in his mother’s footsteps, González Yuen completed a senior thesis on the the feminist influence of the new left while attending Carleton University, a private liberal arts college in Minnesota. His academic advisor, “friend” and “mentor” was Paul Wellstone, former Minnesota senator, community organizer, and leader in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. González Yuen said that Wellstone had an “ability to see people and see the human potential in everybody, which made him an amazing community organizer.”

After college González Yuen worked for the National Center for Youth Law, a program that supports low income, systems-impacted and foster youth. He also interned at a law firm in Chicago transcribing depositions in the civil suit following the murder of Fred Hampton, the Chicago Black Panther leader who was killed by the FBI and the Chicago Police Department.

González Yuenlater applied to University of California, Berkeley and was accepted to both law school and a Ph.D. program in jurisprudence and social policy. He and his wife Jude, who is a clinical psychologist, moved to Berkeley and never looked back. They raised their children in a co-housing community and together they shared childcare responsibilities with another couple.

In Berkeley, González Yuen was energized by the anti-military movement. He worked on a nuclear weapons free campaign that gained national attention surrounding Livermore Labs and Los Alamos where the weapons were conceived. González Yuen wanted the country to see “that we were designing these weapons that had no purpose except for the elimination of humanity and bullying.” He was surprised when all the enthusiasm for this movement petered out. His doctoral work reflected an interest in understanding how to “develop a social movement that is sustainable.”

González Yuen said that his graduate school years at UC Berkeley were “overwhelmingly Eurocentric” given that of 50 full time faculty members, 47 were white men, according to González Yuen. His organizing work with the coalition for diversified faculty “brought about the first woman dean, first African American woman hired and tenured, (and) first LatinX woman hired and tenured.”

Most who graduate from UC Berkeley with a Ph.D./JD are recruited by a large law firm. González Yuen said with pride that instead, he was recruited by De Anza College. The college was interested in “working to dismantle racism in the community colleges,” González Yuen said. He was one of two affirmative action fellows hired.

“I fell in love with it,” González Yuen said.

He loved that the students were working class and just as smart as the students at UC Berkeley, but without the privilege. González Yuen found “that what is recognized as academic skill is usually just privilege. And that if you really give people full opportunities to demonstrate their capacity, they bring their full selves. [With them] you’ve tapped into a goldmine of resources for the society.”

“We all do better, when we do better,” González Yuen said.