On Aug. 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial, looking towards the Washington Monument, and told nearly a quarter of a million people tightly-packed around the Washington Monument’s reflecting pool, “I have a dream….” King’s speech to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was an inflection point in the Civil Rights movement that encouraged the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations to provide more consistent federal government support for desegregation and voting rights in the American South.

Rustin, released November 17, 2023 and now available on Netflix, is an historical drama about how the March’s success was anything but inevitable. The film’s focus is Bayard Rustin (1912-1987), acknowledged in history as the organizational genius behind the March, played by Colman Domingo, and his powerful yet fraught friendship with King, played by Aml Ameen, over the months when the March was organized.

“On the same day I was born Black, I was born homosexual,” Rustin declares matter-of-factly in a scene towards the end of the film. I had first seen Domingo in this scene in Netflix’s pre-release trailer, which set my expectations high. I eagerly anticipated experiencing this scene in situ. When it finally came, “BOOM!” was implied.

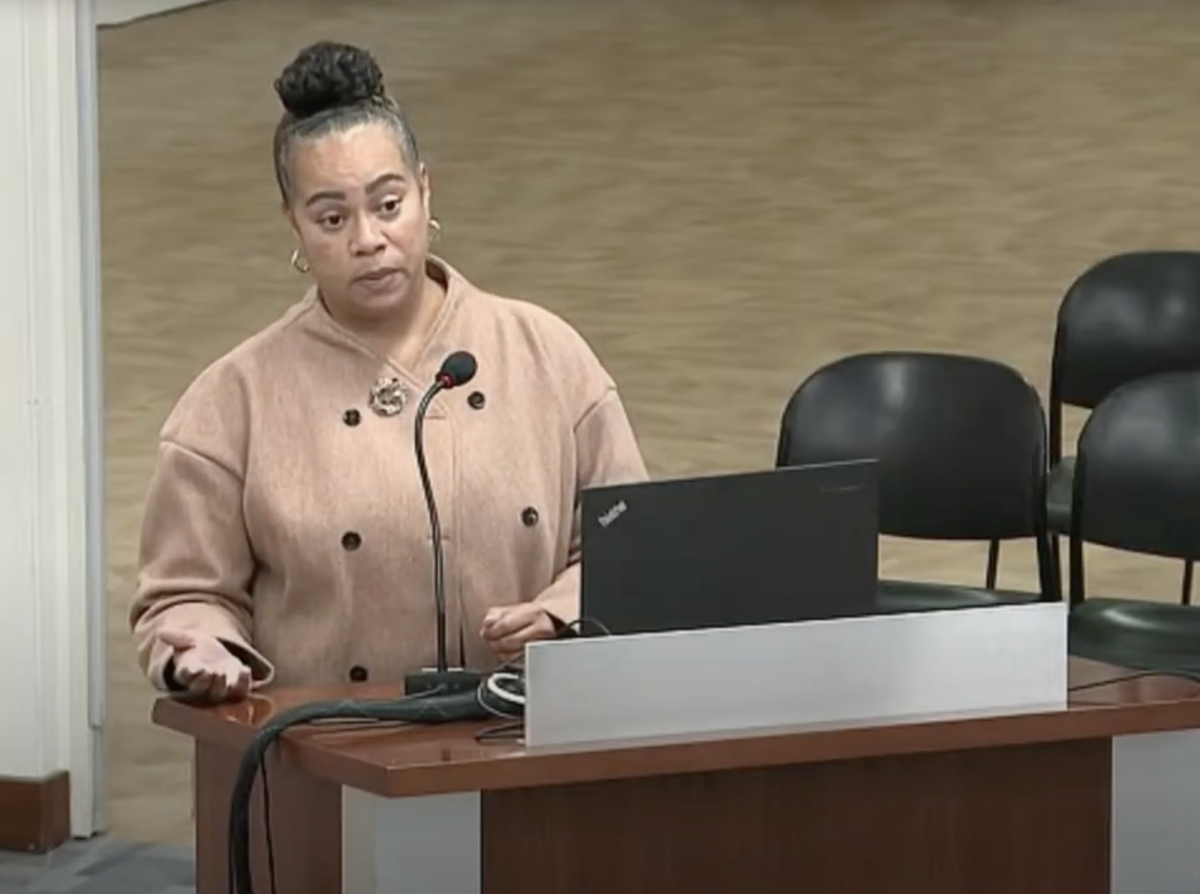

Even if you may not have heard of Rustin’s name in history before, or understand the arc of his life in parallel with better known figures like Dr. King, films like “Rustin” can fill in those less well known parts of narrative history, according to Jeff Sanceri, a Professor of History at the College of Alameda and President of the Peralta Federation of Teachers (PFT 1603). For students who may already have a good deal of factual knowledge about Civil Rights Movement history, films like “Rustin” “can offer the information up in a different way.”

Sanceri expects that Rustin’s story and struggles to be Black and gay would resonate with most Peralta students and community members. “Rustin had at a minimum two very different worlds he had to navigate around his own sexuality,” he said. “This wouldn’t be unrecognizable to queer Peralta students.”

Rustin was nearly 20 years older than King. Raised by his grandmother outside of Philadelphia in the Quaker religious tradition, his early career included Depression-era labor organizing and being a conscientious objector to military service during World War 2. And, he was a homosexual Black man in the mid-Twentieth Century. This resume subjected Rustin to intense negative scrutiny by law enforcement in the rabid anti-communist and anti-homosexual paranoia of McCarthy-era America. For this reason he’s always held an honored space in queer history as someone who led through action and example when it was dangerous to be who you were.

The dramatic arc of the film is Rustin’s daily struggle for dignity among the Civil Rights movement’s leadership as they plan the March. Rustin’s longtime friend, ally, and labor movement leader A. Philip Randolph (Glynn Turman) recognized Rustin’s friendship with King as a “secret sauce” with the potential to unite and transform a still-fractious movement with this demonstration.

But the Rustin-King friendship is on the rocks almost from the minute the movie opens. The big men of the major Civil Rights organizations agreed on almost no strategic approach to planning mass action, except that Rustin’s homosexuality threatened the respectable image that the movement sought to convey, and invited J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI’s relentless harassment of its leaders. This is succinctly portrayed as NAACP’s Roy Wilkins’ (Chris Rock) penchant for contemptuous, backstabbing gossip about Rustin that King fails to defend his friend from, to Rustin’s surprise and disappointment.

Domingo’s outstanding portrayal of Rustin takes place on a plane that is hard to imagine possible for an actor who is not gay to convincingly portray with such subtlety. It’s in the ways Domingo’s Rustin inflects his voice in humorous indignation, or holds a post-coital cigarette, or tosses back a shot of whiskey in a dive bar, or looks hungrily yet cautiously for a lover on the streets outside.

At its best, it happens on an almost cellular level. In a scene where Rustin’s many powerful antagonists among the movement’s leaders berate him with accusations and innuendos, the camera zooms in and lingers on Domingo’s facial muscles twitching back the shame and rage those men seemed hell-bent on inspiring. Before the actor summons the dignified and courageous words by which Rustin defends himself, Domingo’s strained visage dissolves into a wry smile that subtly reveals a black gap in his upper jaw. We learn in another scene that this empty space is the tooth he lost to a policeman’s assault for his refusal to move to the back of a bus.

That small detail plays an outsized role: Domingo’s Rustin strategically flashes it throughout the film like a cape. It does for Domingo what that prosthetic nose did for Nicole Kidman in “The Hours” (2002), or those cat-eye spectacles and fabulous wardrobe did for Lorraine Toussaint in “Selma” (2014). The gap in Domingo’s mouth seems deserving of an award of its own.

A film trying to do as much as “Rustin” is bound to have a few underdeveloped threads. I could watch another whole film about Rustin’s struggles to love and be loved by Tom Kahn (Gus Halper), the young white socialist activist who lives with Rustin for a time; and Rustin’s affair with Elias Taylor (Johnny Ramey), a married Alabama preacher who aspires to King’s rhetorical greatness and Rustin’s ease with same-sex desire. Rustin and Elias’ mutual seduction is realistically acted, beautifully erotic, and punitively terminated. Gays in the audience may find this one of the most compelling yet disappointing story arcs in the film. (Spoiler alert: I was frankly pissed off to find out that Elias’s character was a fictional composite of people who may or may not have existed in Rustin’s life. Still, it’s kind of hot, even as it is a tragic device.)

Other plot devices that may have taken liberties with Rustin’s lived experience include the abrupt transformation of Rock’s Wilkins from rat bastard to effusive ally in the final minutes of the film. It seemed to come out of left field. (Perhaps Rock just got sick of being mean to Domingo?) Similarly, the taming of New York Congressman Adam Clayton Powell’s (Jeffrey Wright) ferocious animus towards both Rustin and King takes place in a single executive committee meeting scene. You will love watching King forcefully stand up for Rustin, and everyone else stand up for them both against the churlish Congressman’s insults. But the relatively smooth sailing for Rustin following this confrontation probably glosses over intersectional tensions that continued to simmer in the movement.

The frustration of women with the movement’s older male leaders was expressed in a few lines by respected New York educator and trailblazing Black politician Dr. Anna Hedgeman (CCH Pounder), that unfortunately felt tossed into the movie gratuitously. This topic is much discussed in academic and popular histories of the Civil Rights movement. This said, and in fairness to the filmmakers, it is hard to imagine doing that topic the justice it deserves in a biopic centered on Rustin’s struggle with those same men. And to be abundantly clear, the movie is very successful at convincingly dramatizing the moral panic those men acted out cruelly towards Rustin in front of the women and young people Rustin had recruited to organize and populate the March, who always seemed to have his back.

Nonetheless, the artistic liberties that may get up an historian’s nose do invest the audience in the drama of one of the most important events of 20th Century America, that was at the time the largest mass demonstration in American history. They enable you to bond with Rustin as the hero, and root for the underdogs, who did actually win big in the end.

The audience is gently re-anchored in history in the film’s final scene. Basking in the overwhelming success of the March, the men of the movement are invited to the White House to meet President Kennedy’s people, with King as their undisputed leader. Rustin remains humbly behind with his volunteers, picking up bits of litter the marchers left behind on the Lincoln Memorial’s steps.

It is a most fitting end to this film, and its tribute to the man Bayard Rustin was. In “Rustin,” we see that transformational leadership is displayed not only on the broad and brightly lit stages of America’s national life, but in mundane activities and care for the many small details that make the public pageantry possible.

Getting a group of friends together to watch “Rustin” would, in my humble opinion, be a great way to learn about and honor the intersection of queer and Black histories this February. However you may do it, just do it!