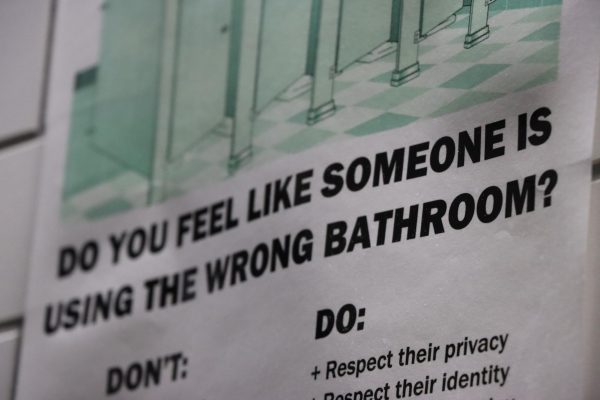

Two months ago a Marina Security guard called out to me, following behind as I entered the men’s restroom on the second floor of the Laney College Library. I knew exactly why he was yelling, and I was tempted to ignore him. After he called out to me a second and third time, I decided to hold my business for one moment to address the man’s concerns.

“This is a men’s bathroom,” he said as I turned to face him through the doorway.

What I said back didn’t matter as much as the deep voice I spoke to him with. He quickly walked away from me with a sheepish, “My bad, bro.”

Initially I didn’t consider reporting the confrontation. It was humiliating, but I wanted to give him the benefit of the doubt. ‘He only saw me from behind,’ I thought. ‘Surely his intention was to spare me from embarrassment. No point in dragging this into a whole process.’

This wasn’t the first time I’ve been questioned on my choice of bathroom. With my long hair and short stature, I’m occasionally mistaken for a woman. Being called “miss” in public doesn’t shock or offend me, even as a transmasculine person. Most are quick to correct themselves when they see facial hair, and I laugh it off.

What I can’t laugh off is the knowledge that bathroom confrontations around gender expression can – and do – escalate into violence.

I think of examples like Nex Benedict, who was a 16-year-old high school student from Owasso, Oklahoma. Benedict identified openly as non-binary, and used “he” and “they” pronouns. As many gender nonconforming students do, young Benedict faced a great deal of transphobia at school, from administrative officials dictating a sex-based school bathroom policy down to peer bullies that targeted Benedict and their friends.

On Feb. 7, Benedict was attacked in the girl’s bathroom at their school and beaten until they blacked out. They died the next day.

When their death began to attract national attention, the Owasso Police Department released a statement on Facebook that Benedict’s family criticized for releasing sensitive information prematurely and ruling out “trauma” as a cause of death. An official autopsy of their body determined that Benedict had died by suicide, an outcome which The Advocate, an LGBTQ-focused news publication, openly called into question.

A few weeks after my encounter with the guard in the library, the Tulsa County District Attorney announced no charges would be filed around Benedict’s death.

After I learned about the decision, I was no longer concerned with my own personal discomfort. There is no gender neutral bathroom available in the library for students like me – no matter which one we choose, we risk being confronted about our perceived identity. So if a security guard at my school felt comfortable confronting a visibly gender nonconforming student in the “wrong” bathroom once, it has probably happened before, and will happen again.

I looked for a way to report harassment on the Laney College website, on the Marina Security homepage, and then on the Peralta district website. There was no online form to fill out. I had to read the raw text of AP 3435, the administrative protocol for reporting harassment, to understand what to do next: provide the district with “facts with enough specificity to show that the allegations, if true, would constitute a violation of District policies or procedures prohibiting discrimination, harassment, or retaliation” in the form of a verbal or written complaint.

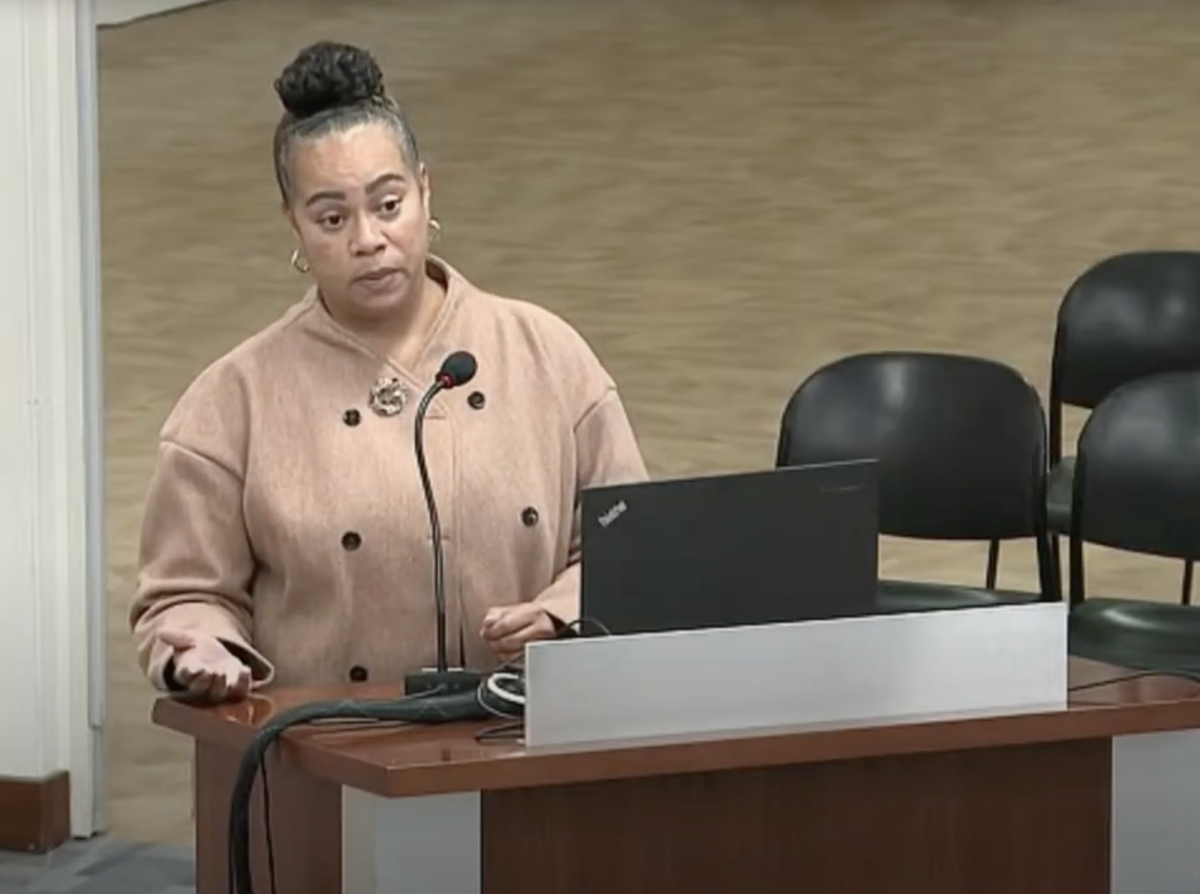

I wrote an email to Marlon Hall, the Acting Vice President of Student Services and Title IX Coordinator at Laney College, explaining what had happened. I provided as much detail as I was able to, including the time and exact location where I was stopped. I described the guard who had stopped me, certain that I would recognize him again if I saw him.

At first, Hall responded to my complaint by directing me to read AP 3435. “A formal complaint to my office with [sic] move this item forward,” he wrote.

“I familiarized myself with the text of AP 3435 before I sent my initial email,” I sent back, explaining that I’d already met the criteria for a complaint defined by the document.

“We will meet upon my return on Monday,” he replied. “I will set up a time.”

I waited all week, being sure to keep my Monday clear to accommodate a meeting. Come Monday morning, I received an email that Hall would be available that afternoon. A few hours later I was seated in his office, learning that my grievance had hit a wall. Hall was polite but clear: even though he considered this to be a serious case, an investigation could not go forward without the guard’s name.

I was dumbstruck. Was I supposed to potentially escalate a harassment situation by asking, “Hey, what’s your name? Can I see your badge?” But as Hall explained to me, it was my “right” to do so with campus security. I asked if Marina security guards receive any diversity training– he said, “They have to.”

“Do I have any recourse?” I asked him. I suggested checking any available security cameras, or looking at schedules to narrow the possibilities down to whichever security guards were working at the library that night. He wrote these ideas down onto a sticky note, pressed it to the edge of his computer monitor and let me know he would follow up with someone.

Before I left, he made sure I received a thick booklet that read “Unlawful Discrimination and Sexual Harassment: Complaint and Investigation Procedures for Employees and Students” at the top in large, bold, capitalized text. Towards the back was a form for submitting a formal complaint, which Hall indicated I should fill out and submit to him in order to proceed.

One of the required fields on the form read, “I wish to complain against:”, leaving a blank space for a name which we both knew I could not produce alone.

I thanked him for his time, and he let me know it was no problem. “Students are my job,” he said as I walked away.

The papers were heavy in my hands. Hall had a friendly, helpful demeanor during our meeting. But he’d only helped in explaining why he couldn’t do much for me. I felt uncertain and hollow.

I still love the Laney library, but hanging out there hasn’t felt the same since that day. Now it reverberates with echoes of the rumors, teasing, and awkward questions that hounded me around my high school when I started transitioning. I will never forget the teachers who could not be bothered to conceal my old legal name during roll call, or the resentment and alienation that made me skip class altogether.

Over many years, that pain has formed into a sore callus of resolve that drives me forward as a student and as a writer. But moments like this take me right back to being a bullied 16-year-old kid.

For transgender students, mental health is intrinsically tied to their safety on campus. It doesn’t matter whether Benedict died by suicide or was murdered. As former Oklahoma teacher Tyger Songbird put it, the “culture war” is what killed them.

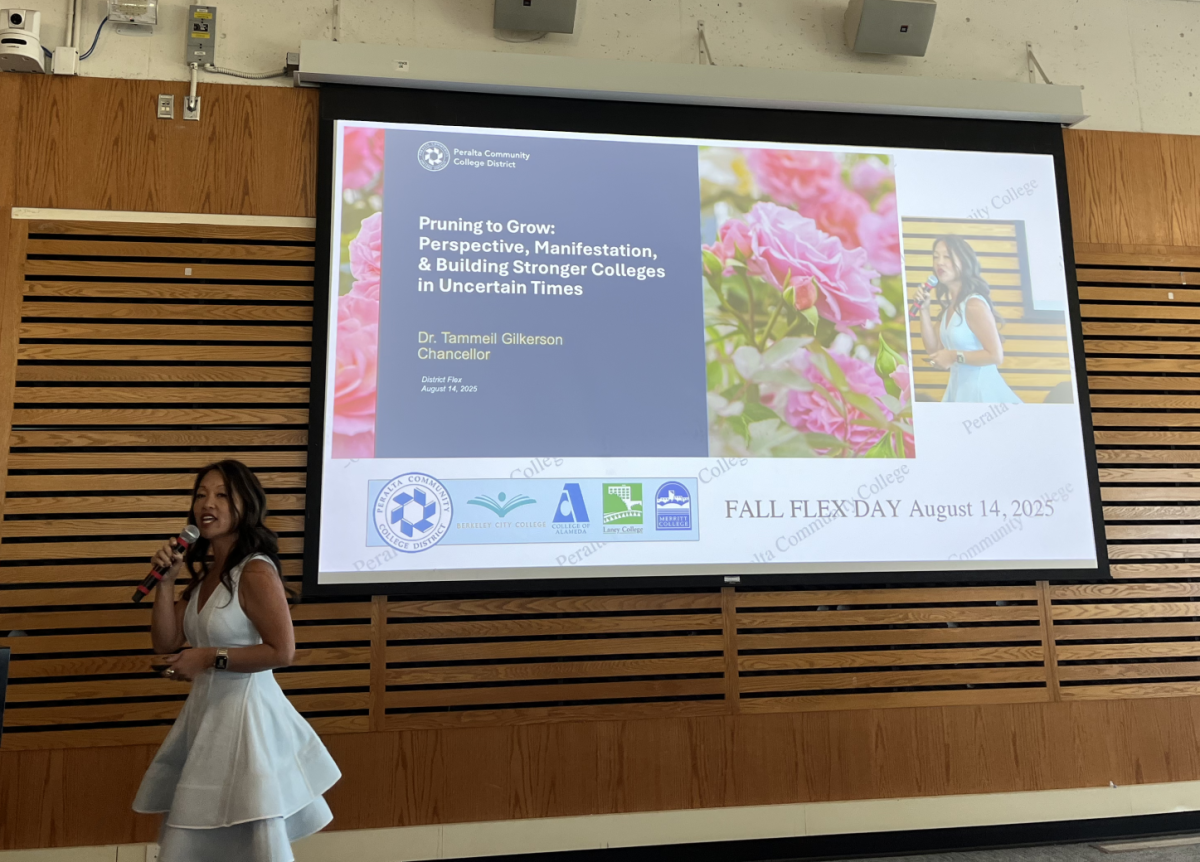

If the Peralta school district wants to be welcoming to LGBTQ students, it needs to do more than host a graduation for queer students, and offer a handful of gender neutral restrooms on its campuses.

In a time where federal Title IX protections are being eroded, our district needs to be vehemently on the side of our right to exist everywhere, not just the safe spaces. It’s on Peralta to protect students from harassment, transphobic or otherwise. The process for reporting that harassment should be as simple and transparent as possible. How can Peralta protect us students when we aren’t equipped with the tools to effectively respond to misconduct before it happens?

We deserve better. In the meantime, Peralta students can fill out this form to report experiences of harassment and illegal discrimination on campus. It can be submitted to your college’s V.P. of Student Services, your college’s President, or Peralta’s Vice Chancellor of Human Resources. Use it early, use it often, and don’t forget to ask your harasser how they spell their name.