This article was published to CalMatters on July 9, 2024.

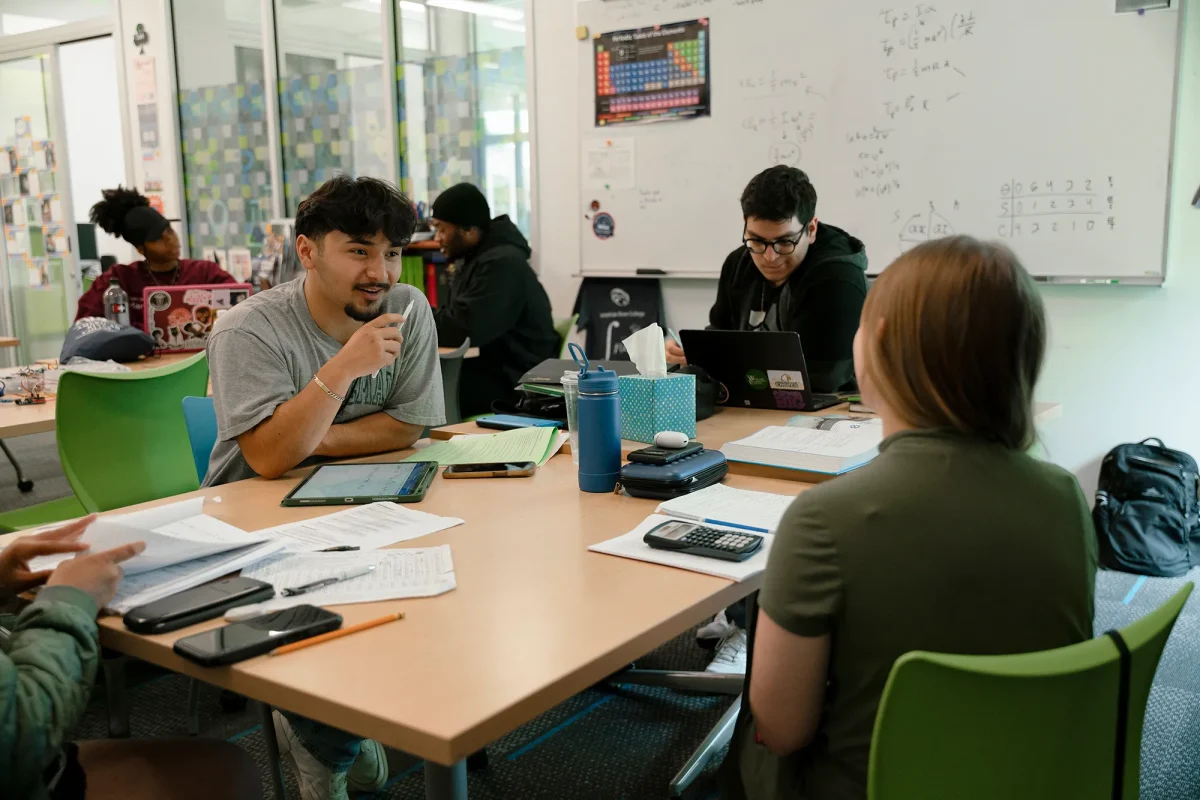

Alina Kralya tinkers with a microcontroller for one of her computer science projects at American River College. Nearby, a group of other first-generation college students sit in green and blue chairs, chatting about their math homework. It’s a typical scene at this community college space for students in the Math, Engineering, and Science Achievement program, called MESA.

Two years ago, Kralya was in her first year at an engineering university in Ukraine when the Russian invasion and the subsequent war uprooted her family. After moving around Eastern Europe, they sought refuge in sunny Sacramento with $300 in their pockets.

Between language barriers, a brand new academic system and trying to make sense of trigonometry, it hasn’t been an easy journey for the 20-year-old, who dreams of going into robotics. When she needs tutoring or just a quiet place to study away from her younger siblings, she comes to the MESA center.

She’s still buzzing with excitement about a recent conference for female engineers she attended in San Jose. The program covered her entrance fee and transportation costs, and staff helped her set up her LinkedIn profile for the event. “Listening to all those successful ladies in STEM, oh my gosh, it was so nice,” she said.

California allotted millions of dollars in 2022 to create the same program at community colleges across the state. Currently, 91 out of 115 campuses have programs established, with three more set to create one next year. The state hopes the expansion will reduce barriers to STEM jobs for “underserved and underrepresented” students. As the initiative rolls out statewide, questions remain about how long the funding will last, and how the programs can track how well they’re working.

To enroll in the program, students must be both low-income and a first-generation college student. The students’ parents can’t hold a bachelor’s degree in any country to meet the first-generation requirement.

Less than 1 in 5 community college students in California who want to transfer to a university succeed in doing so within four years, according to a report from the Public Policy Institute of California. For Black and Latino students, transfer pathways are even weaker: 13% for Black students and 16% for Latinos.

Beyond bolstering transfer rates, the goals for MESA include increasing representation of Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans in STEM industries. In 2021, 9% of STEM workers nationwide were Black, while 15% were Hispanic or Latino, according to a report from the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics.

“The community needs people to be in these positions as doctors, as scientists, as engineers, as computer scientists who actually understand the community that is being served,” said Edrina Rashidi, the officer of advocacy for the Community College Association of MESA Directors, who recently lobbied for more legislative support for the programs.

Students in the program have access to a range of support, such as tutoring, academic counseling and help finding internships or scholarships. The physical centers offer computer equipment, textbooks and a place to study. Program directors work closely with students to connect them to resources.

As of fall 2023, 4,279 students were enrolled at a MESA program on their campus, according to state data.

State funds expansion of MESA programs systemwide

Four years ago, MESA programs had a $2.5 million statewide budget. After lobbying efforts from the MESA directors association, the program now has a $39.4 million statewide budget and was written into the California Education Code. Over 50 colleges have taken advantage of the funds in the last two years, nearly tripling the number of programs from 34 to 94.

Each college received a total of $428,576 for the 2022-23 school year, in the form of a grant from the state. This past year and every year through 2027 they’ll get at least $280,000 each. However, the state chancellor’s office expects colleges to eventually start covering some of the costs, so that the programs can stay afloat if the state money disappears, according to the statewide MESA project monitor Stephanie Ricks-Albert.

The state grants will be up for renewal in 2027. Rashidi said more legislation is being written that could establish a minimum funding level, to guarantee stable funding for the programs.

The program also exists in different forms across the state and nation. In California, many universities and high schools have MESA programs or clubs that are overseen by the UC Office of the President with a budget of about $7 million.

Inside a MESA program

Computers, STEM textbooks, whiteboards, a free-to-use printer and a coffee machine occupy the MESA center at American River College, housed on the first floor of the sleek new Diane Bryant STEM Innovation Center. A line of university pennants hangs from one wall; on another, three astronauts smile from a poster that reads, “FROM MESA TO NASA.”

Over 200 students have access to this space. It’s where tutors like Marco Alaniz, who is also a MESA student studying computer science, can often be found. He’s had a love for programming since his mom bought him a computer as a little kid, but he struggled when he started college the first time over 20 years ago, and ultimately dropped out.

“I just wasn’t prepared,” Alaniz said. Because his parents never went to college, they didn’t have the experience to help him navigate school or teach him time management habits. “So really, growing up, I was kind of on my own on that, just kind of figuring things out.”

After about 15 years of working odd jobs to pay the bills, Alaniz enrolled in American River College in 2019 to give his computer science degree another shot. For the past year he’s tutored MESA students. It doesn’t pay enough for him to quit his job so he can take classes full time, but he really enjoys breaking down difficult concepts for his fellow classmates, and it’s even made him consider a career in education.

Samuel Morrison, the college’s interim MESA project lead, explained that the cost of living is one the biggest challenges for the low-income students he serves. He helps connect them to scholarships and internships, as the programs are required to do. One creative way the college has found to financially assist its students is to create paid projects with faculty mentorship and research opportunities students can apply for.”

“So students are finding, OK, this is a stipend that I can use to pay for gas to get to school, or I can use to supplement food costs,” Morrison said.

Still, the college lacks a designated MESA academic counselor. Kralya, the Ukrainian student, explained that the general counselors she’s seen are not always familiar with STEM-specific transfer programs, which can differ between universities. Adding financial aid to the mix makes things even more complicated; Kralya and Alaniz both had to declare multiple majors to get certain transfer requirements covered by financial aid.

“That’s why we have to find a really good counselor who can tell us this, because this information is not listed anywhere,” Kralya said.

The state requires the programs to have designated counselors, but getting an in-house counselor can be a lengthy and complicated process, Morrison said. He hopes to have one on board by the spring of 2025.

Students can also sign up for field trips, which include conferences and college tours. Students this semester visited the Sacramento State University planetarium, attended the Women in Engineering conference in San Jose, and toured UC Berkeley and UC Santa Cruz.

At programs across the state, students who are either low-income or first-generation, but not both, can still access certain resources, such as tutoring and counseling, but can’t go on field trips or receive paid research opportunities. There are currently 1,345 of them enrolled systemwide, called ASEM students, or “Friends of MESA” at some colleges.

Growing pains as programs roll out systemwide

Two years after new funding opened the doors for more programs, many still need to hire staff, find the required minimum 500 square feet of space to house the center, or recruit students to officially get off the ground.

Just hiring a program director to lead the program can be a lengthy process. A year and a half after receiving its grant, the program at Laney College in Oakland is still without a director. The college’s dean of math and sciences, Inger Stark, appointed math instructor Kyla Oh as the program’s faculty lead for the program in the interim.

“It has definitely slowed us down,” said Stark. The bulk of the work falls on Oh, who teaches fewer credits so that she has time to focus on the program. Stark squeezes the administrative side of the program into her workday as a dean.

Right now, the state money covers the entire program, which launched in April with an initial cohort of 14 students. Stark is determined to ensure the program stays afloat through any changes in the funding, but she’s spent enough time in her community college district to have seen many “beautiful initiatives” get weeded out.

“It is heartbreaking,” she said. “A huge amount of work can fall on the ground.”

The need for more granular program data

Tracking MESA programs in a comprehensive way is not easy. Some basic data is available through public dashboards, but directors want easy access to more in-depth information about their programs to help make sure they’re meeting their goals.

“We actually have no way of measuring our success, still, with the Chancellor’s Office,” said Rashidi, the lead advocate for MESA directors.

Basic information, such as the total number of MESA students in the system, is available through the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office public data tool, DataMart. However, that information isn’t broken down by race, gender or major. Granular data could give program directors the ability to quickly check if their efforts to reach students from underserved backgrounds are working.

Limited information on MESA student success is publicly available. Of the MESA students who first attempted to complete a transfer-level math course in the 2021-22 school year, 79% passed within one year, compared to a 54% completion rate for the general student body, according to the Transfer-Level English and Math Completion Dashboard.

CalMatters requested MESA transfer statistics and racial data from the Chancellor’s Office. According to the data, about 62% of MESA students were Hispanic or Latino as of December 2023, while 4% were Black.

To count transfers, the Chancellor’s Office counted students who were in MESA in one school year, and then enrolled at a university the next year. By this metric, MESA programs collectively transferred 1,010 students after the 2021-22 school year, including 563 Hispanic or Latino students and 23 Black students.

Nearly half of MESA students enroll at a university within four years of taking their first community college class, as of 2017, the most recent year complete data is available. Students were considered to be MESA students if they participated in the program at any point during their first three years in the community college system.

The Chancellor’s Office will analyze the status of the programs at the end of the current grant cycle, and the results could affect how much money programs will receive in the future, according to an emailed statement from Melissa Villarin, a spokesperson for California Community Colleges. Any additional funding would be based on “program and campus metrics,” according to the statement.

Khan is a fellow with the College Journalism Network, a collaboration between CalMatters and student journalists from across California. CalMatters higher education coverage is supported by a grant from the College Futures Foundation.