This story was published to CalMatters on Dec. 4, 2024. Managing Editor Lylah Schmedel-Permanna is a fellow with the CalMatters College Journalism Network.

Seeing is believing — at least, that is how Jae’Shaun Phillips feels about attending Sacramento State, the California State University with the largest Black student body, with over 2,000 students. He is in the inaugural class of the Black Honors College, a new initiative created to support future Black scholars and leaders.

Now, Sacramento State is leading similar charges statewide. For one, the university is hosting the Cal State system’s new Office for the Advancement of Black Student Success, which oversees efforts to better serve Black students throughout the Cal State system. Secondly, on a wider scope, this office will soon manage a special designation for California colleges and universities that demonstrate a strong dedication to their Black students.

A new law taking effect Jan. 1, enacted as SB 1348, creates the first official Black-Serving Institution designation in the country. The designation will be given to qualifying colleges that vow to take a more aggressive approach to address California’s systemic obstacles that have kept Black students at the lowest college-going and graduation rates. Though it’s not stated in the law explicitly, the intent is that both public and private nonprofit institutions are allowed to apply, according to the office of Democratic state Sen. Steven Bradford of Inglewood, who authored the law. This designation is not federally recognized nor will campuses receive federal funding.

Besides meeting other student support requirements, the designation is only available to institutions that have a Black student enrollment of at least 10%. For campuses that can’t meet the 10% threshold, they must have at least 1,500 students who are Black. Students like Phillips find comfort in these numbers.

“I feel like it pushes me further, just seeing a lot of motivated people, our colors, trying to [succeed] in college,” Phillips said.

This is not the reality for most Black college students who find themselves a minority in the majority of California classrooms. California colleges and universities educate over 217,000 Black college students in a pool of over 3.4 million.

California’s Black students trail behind their peers academically. Two-thirds of the state’s Black students start at community colleges yet only 35% transfer to a four-year university within six years, compared to 45% for white students, according to an independent study using California Community Colleges data. Cal States lag in graduating their Black students at 49% within six years compared to 62% overall, according to U.S. Department of Education data. At the UCs, where Black enrollment is the lowest, 78% of Black students graduate in six years but are still 8 percentage points behind the general population.

Bradford finds those statistics “concerning,” further noting that Black undergraduate enrollment nationwide has declined 25% between 2010 and 2020. Bradford hopes this new law will reverse the enrollment decline by recognizing colleges that are “accepting and open and there to support African American students.”

In California, no colleges or universities meet either of the two primary federal designations for serving Black students: Predominantly Black Institutions, which must have at least a 40% Black student population, and Historically Black Colleges and Universities, which apply to schools established before 1964 with a primary mission to educate Black students.

How campuses will qualify as Black-Serving Institutions

The Office of Black Excellence will oversee the applications from campuses seeking the Black-Serving Institution designation. Designees will be selected by a governing board consisting of the lieutenant governor, the chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus, two members of the public, and college and university officials representing public and private, nonprofit higher education institutions.

To qualify for the designation, schools must have established programs dedicated to Black student success, a yet-to-be-determined track record with Black retention and graduation rates, and a five-year plan to boost those rates.

Bradford’s office says the governing board will clarify ambiguities in the law regarding application requirements and determine the logistics once it convenes in January. The law does not outline the requirements for two-year nonprofit private institutions applying to the designation nor does it stipulate a deadline for when the first Black-Serving Institution will be recognized. The law is also unclear about which student enrollment data, self-reported or federal, schools will use to show eligibility and whether they can include both undergraduate and graduate students.

Self-reported data introduces the potential for inconsistency in how the board vets the institutions — in some cases the numbers nearly double. For example, the UC system indicates that 4.5% of its undergraduate students are Black. However, according to federal Department of Education data, that number is just 2.3%.

According to 2022 federal counts of undergraduates and graduate students, 60 California colleges and universities meet one or both of the student population requirements to be a Black-Serving Institution. Of those schools, 32 are private nonprofits, 24 are community colleges, three are Cal States, and only one is a UC — UCLA with 3.6%, or 1,681, Black students. However, according to UC’s self-reported data in 2022, two of the 10 UCs reported more than 1,500 Black students. That number jumped to four in 2023.

This is because the UC system counts a person of mixed race as a single race based on a hierarchy that places the highest priority on Black students. UC data rules state that a student who self-identifies as Black and any other group will be reported in UC’s system as Black. Meanwhile, federal data counts mixed-race students in a separate “two or more” category.

The Cal State and community college systems also publish internal demographic numbers that vary somewhat from federal data. Unlike the UC, these systems use a category of two or more racial groups. Private, nonprofit institutions operate independently, making it difficult to assess each college’s internal methodology.

Some campuses already dedicated to Black student success

A few campuses that have confronted inequities served as the blueprint for the new Black-Serving Institution designation. Keith Curry, president of Compton College, and Luke Wood, president of Sacramento State, worked closely with Bradford’s office to conceptualize the law.

Both presidents say they recognize the limitations imposed by Proposition 209, passed in 1996 to ban race-based admissions and education programs, and emphasize that their programs focus on minority students but are open to everyone.

In 2022, Curry proclaimed Compton College a Black-Serving Institution, encouraging educational leaders to serve Black students “unapologetically” in an Op-Ed for Diverse magazine. Located south of Los Angeles, Compton College has 1,204 Black students, a quarter of its population.

Curry said he harnesses the power of culture to boost student interest with events such as Black Welcome and Black Graduation. This past spring, rapper Kendrick Lamar spoke at graduation, creating some social buzz.

In 2021, Compton College created a new leadership role, director of Black and Males of Color Success. In the role, Antonio Banks connects students to tutoring services, basic needs resources, and specialized programming. He also oversees the Men’s Leadership Academy, which hosts weekly events dedicated to community building, such as the recent “Babyboy: Building Emotional Intelligence to Combat Toxic Masculinity.”

Banks said they focus on fostering community and “helping students become advocates, both in their own fight for education, [and] the fight for others.”

Curry believes his Black-centered approach is already working. During the 2023-24 academic year, returning Black full-time equivalent students increased 34.6% from the previous year, according to Compton’s data. Banks says it will take one to three years to fully reveal the impact of their programs on graduation rates.

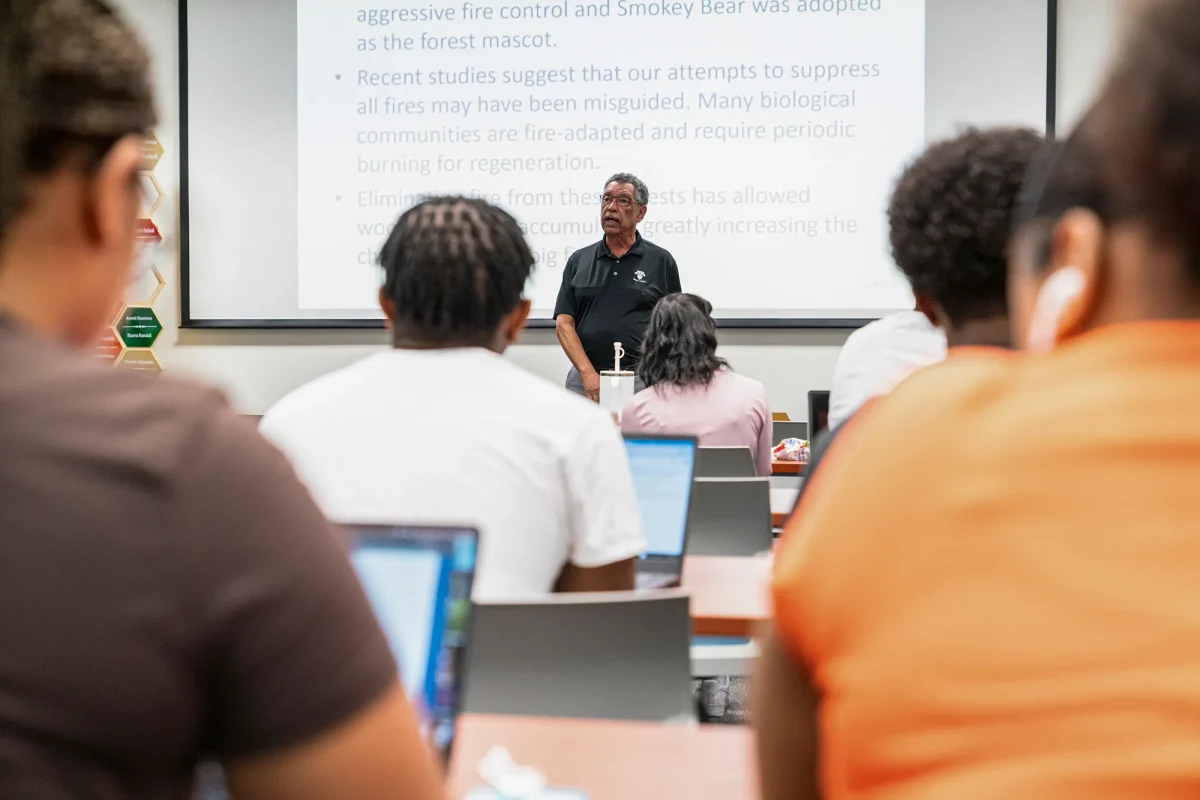

In the Cal State system, Wood has been a leading advocate in supporting Black students. A 2023 report by the chancellor’s Black Student Success Workgroup acknowledged the university system’s failure to produce equal outcomes for its Black students. The report made recommendations to all Cal State universities, including recruiting faculty with a high record of success in serving their Black students, implementing inclusive curriculum, and establishing a Black Resource Center on every campus. Much of what the report entails, Sacramento State has already established.

Sacramento State hosts over a dozen groups and resources dedicated to supporting Black and marginalized students. “We’re trying to create an experience outside of the classroom that celebrates Black history, life and culture in a way that you would only see at an institution that is a HBCU,” Wood said.

An example is the Black Honors College, which focuses entirely on Black academia and culture. Select students receive specialized staffing and resources for seminars, coursework, therapy, research opportunities, housing, and more. The university has also started establishing pipelines with some community colleges with large Black student populations, including Merritt College in Oakland and Compton College.

Business major Phillips attended predominantly white grade schools in Tracy, California. One of the reasons he chose Sacramento State was the community it has built for Black students.

He said initiatives like the Black Honors College have special impact on “kids who are very strong in academics, but may not have that home life that really supports them, or for kids who have a lot of capability, potential and talent, but [are not] being promoted or pushed through all the way to see that full potential.”

Wood says their efforts have already helped in recruiting and graduating Black students. Applications overall were up by around 4,000 this fall, with a 17% increase for enrolled Black freshmen and a 40% increase among Black community college transfers. Four-year graduation rates for Black students rose to 1 in 4 graduating in 2024, compared to 1 in 5 in 2019.

Students have mixed feelings about campus support

Universities that pursue the new Black-Serving Institution designation seek to attract students like Nora Thompson, who is studying administration of justice at Merritt College and has always wanted the HBCU experience. Merritt serves a 20.4% Black student population. Thompson has plans to transfer to North Carolina Central University, an HBCU, in the spring. She dreams of becoming a judge like her grandfather.

“I had to work 30 times harder to be seen as a student and as someone who cared about their education,” Thompson said. “For most people, their HBCU changes their life … I wanted to experience feeling like being part of a community in every possible way, not just education wise.”

She lamented having to leave the state — and pay out-of-state tuition — just to experience a flourishing Black academic setting. Thompson says that even with the Black-Serving designation, California’s Black student populations are not enough to keep her here.

Further north in a more remote area of the state, junior journalism major and Black Student Union president at Cal Poly Humboldt, Kaylon Coleman, is not satisfied with his experience at the university — from the subtle racism by his classmates to the few opportunities to learn from Black scholars.

Cal Poly Humboldt is a predominantly white institution. Federal data as of 2022 shows that of the 6,025 students enrolled, only 179 were Black — far below the minimum to qualify as a Black-Serving Institution.

As a freshman, Coleman was told by counselors that the Black Student Union had a history of disbanding due to low Black student enrollment. He turned to the Umoja Center for Pan African Student Excellence, the university’s cultural center for those who are Black identifying or of African descent. A friend of Coleman’s revived the union, and he joined.

Like many students attending universities with small Black populations, Coleman said it’s exhausting to speak up about the behavior of those around him.

“It’s hard to be that one person — Black person — in your class, or the one to explain why this was a microaggression, or why this was racist, or why you can’t touch my hair, stuff like that,” Coleman said.

Coleman feels that students attending schools without the Black-Serving Institution title will be left behind. He believes that Black students at every California college deserve to reap the benefits that would come with the label.

Kyira Todmia, a senior in neurobiology, physiology, and behavior at UC Davis, shared a slightly different experience. In 2022, federal data reported Davis had 783 Black students, representing 2% of over 39,000 students total. However, it self-reports 1,472 Black students, or 3.7% of the population. She says that while her school may not have a large Black student population, the student resources are strong.

Todmia built her social circle around the African American “learning community” in student housing as a freshman. She also hangs out at the Center for African Diaspora, where students have access to study spaces, tutors, peer advisors and events.

During Todmia’s four years at Davis, she’s only had one Black professor. Because few Black students are in STEM majors, at times she is the only Black student in classes of 300 to 500 people. At least in her learning community, she said, she was able to see rooms full of Black folks every day — even if they weren’t in most of her classes.

For Sen. Bradford, now 64, the new law is personal. Bradford reflected on his own experience as a biology student at Cal State Dominguez Hills in the 1980s.

For a campus that earns the Black-Serving Institution designation, Bradford said, “It’s going to be an environment that’s going to be welcoming, that’s going to be supportive. I only wish that had existed when I entered college over 40 years ago.”

Mikhail Zinshteyn contributed to this story.

Lylah Schmedel-Permanna and Jasmin Shirazian are fellows with the College Journalism Network, a collaboration between CalMatters and student journalists from across California. CalMatters higher education coverage is supported by a grant from the College Futures Foundation.