Investigative reporter warns of a journalistic ‘crisis of confidence’

by Eva Hannan

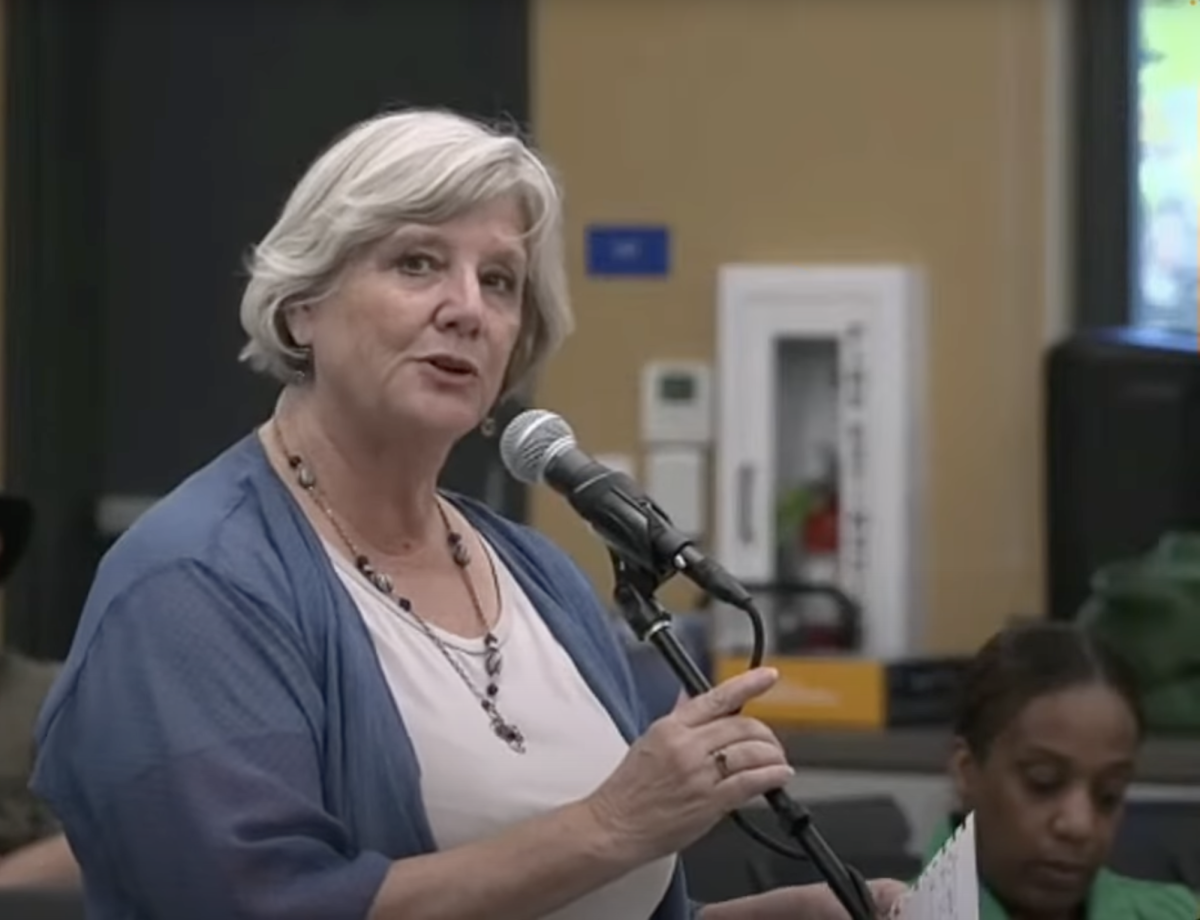

Unlike many former Laney College students, Martin Reynolds returns to campus every so often when he is invited to speak. His latest appearance, in the Survey of Mass Media class, was Feb. 27. He hasn’t been enrolled here since 1993, but his expertise of the challenges facing journalists past and present is valuable to students interested in understanding the way people get their news.

He spoke about shrinking numbers of news sources, lack of diversity, and the paradox that results from profit-based news, which are all challenges facing journalism today.

The former editor-in-chief of the Oakland Tribune has witnessed the national and local media narrowing their focus and resources until, as he said, the country now faces a crisis of confidence that threatens the very existence of a free press.

He currently holds leadership roles in two non-profit news organizations in the Bay Area working to save the future of journalism.

One is the Maynard Institute in downtown Oakland. The other is the Center for Investigative Reporting in Emeryville. Part of the focus of each is to improve the funding and diversity of investigative reporting.

“Journalism is not bleach,” Reynolds said. “It’s not an iPhone, it isn’t only about making money. It’s the history of a community.”

The Maynard Institute, founded in 1978, is dedicated to helping America’s newsrooms reflect the diversity of these communities.

Reynolds said that the institute was born out of the Civil Rights movement. At that time, journalists needed to “go into the ghettos of American cities and talk about what was going on with the riots in Detroit, in Newark.”

No one would do that, because almost all of the reporters were white and fearful of the violence.

In 1978, only four percent of journalists were people of color. Today, they account for 13.5 percent of the field, according to the institute’s website.

The institute is helping this number continue to rise so it reflects an accurate representation of the diversity of the nation.

In 2016 they created the Investigative Fellowship Program and named Reynolds as the director.

He continues to implement the program he was integral to building, which gives journalists of color training to move into the field of investigative journalism.

The goal is that a story will never go uncovered again just because the subjects aren’t white.

“The level of backsliding in these last 50 years is telling,” Reynolds said. “It’s ironic that at the time [of the Civil Rights Movement], the media was ill-equipped to cover the strife, to make sense of it for society.”

“Right now, the media is once again ill-equipped.”

News sources are unable to construct a national dialogue that accurately confronts what has become paramount to many Americans — equal opportunities and equal compensation for work. The institute is changing the way the media form a common narrative one newsroom at a time.

The focus is for staff to change the way they interact. In many newsrooms there are stories that may be important to a lot of people, but not the “very, very white, very male, and rather old,” people in charge, Reynolds said.

The institute trains members of a news organization in “cultural competency.” If they have micro aggressions or trouble deciding what to cover and how to cover it, they can get “fault lines” training.

The concept of fault lines is that people can have differing points of view “through the prism of race, class, gender, generation, and geography,” Reynolds said.

The late Oakland Tribune publisher Bob Maynard, co-founder of the institute, came up with fault lines in the late 1980s.

Availability of different viewpoints in the newsroom can go a long way toward cultural relevance in reporting but that is only part of the issues facing journalism in the modern era.

Deregulation of the media began in the early 1980s during the Reagan administration, and since then, most media outlets have come to be owned and controlled by one of a few huge corporations.

The largest media companies of 2017 were Alphabet Inc. (holding company of Google), Disney Inc., Comcast, 21st Century Fox, and Facebook.

Together, they control a decisive majority of the news coverage in this country.

Journalism that operates with maximum profit as motive is unraveling the core functions of a free press in a democracy, Reynolds said.

The Center For Investigative Reporting is leading the charge for change. Five years ago, advertising and sales almost exclusively funded news outlets. Now, even for-profit news companies accept grants for projects.

“It’s about capturing history, it’s about accountability, and if you’re gonna be in this business you gotta recognize that,” Reynolds said.

The center works in more than just print media. They also largely fund the investigative radio series “Reveal.” Each episode features in-depth stories that can take a year to research and garner over one million downloads on iTunes.

Reveal’s recent piece about bank loan practices in American cities, “The Red Line: Racial Disparities in Lending,” has sparked national debate and investigations across the U.S.

The Glassbreakers Fellowship Program helps women filmmakers, and recently led to the production of “Heroin(e),” a Netflix-featured documentary on the opioid epidemic in West Virginia, directed by Elaine Sheldon, that was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject this year.

Reynolds co-founded Voices in Oakland and Sacramento, which trains community members to tell their stories for publication in local media sources.

He said he respects citizen-journalists and projects such as the City Bureau in Chicago and Detroit, but that ultimately there’s no substitute for the kinds of stories produced by a well-oiled newsroom.

“It’s not just a skilled journalist who knows how to file public records, to cultivate sources, and is an excellent writer with the skills to contextualize,” he said. “There’s also a back-end of editors, copy desk, design team and photographers.”

Thanks to efforts from the Center and the Institute, there is not only hope for the future of journalism, there is already a map of how to get there.

Eva Hannan is a Tower staff writer.