By Brian Howey

Broken glass scrapes underfoot, glinting in the muddy lamppost light as David Hernandez walks toward a cluster of tumble-down tents huddled under a MacArthur Freeway overpass. It is the early morning of Jan. 31, and the encampment is cold and still.

One man stands among the tents, quietly smoking a cigarette.

“There’s someone over there,” Hernandez says, pointing.

Quyen Tran lifts her clipboard and marks the man, and the encampment, on her count sheet. The pair moves on.

As they walk, they scan empty lots and circle RVs, searching for tents and tarps, fogged or blocked windows: signs of the homeless.

So proceeded the ninth biennial homeless census, or Point in Time Count (PITC), an effort to tally the homeless population of Alameda County to provide statistical data for local homeless outreach programs and the public.

The count was organized and funded by EveryOne Home, a collaboration of the Alameda County government and city governments within the county.

EveryOne Home worked in conjunction with Applied Survey Research, a California-based social research firm in order to pull off this year’s count.

Outreach

This year’s PITC was the first to use a blitz-style tallying method, using guides from homeless communities to help volunteers find and count people, encampments, and lived-in vehicles throughout the county.

For the count, a guide was assigned to each group of volunteers (usually 2–3 people), and the group then assigned an area to survey. Carrying printed maps of their assigned areas and count sheets to detail their findings, the groups scattered from six different deployment points in Oakland, Livermore, Fremont, Hayward, and Berkeley.

One of about 100 guides who worked for the count, Hernandez had the task of showing volunteers for the PITC the locations of well-known homeless camps and RV locations in their assigned areas.

Many of Oakland’s guides were recruited by Operation Dignity, a non-profit organization which specializes in transitional housing and outreach for Oakland’s homeless population.

As an incentive to participate, guides were paid $15 per hour for their time, paid in cash at the end of the count.

Hernandez, 25, has been homeless for nearly two years. He asked that his real name not be used.

“I’ve been back and forth between the streets and the warehouse,” he said, referring to a warehouse in West Oakland where he occasionally works as a laborer.

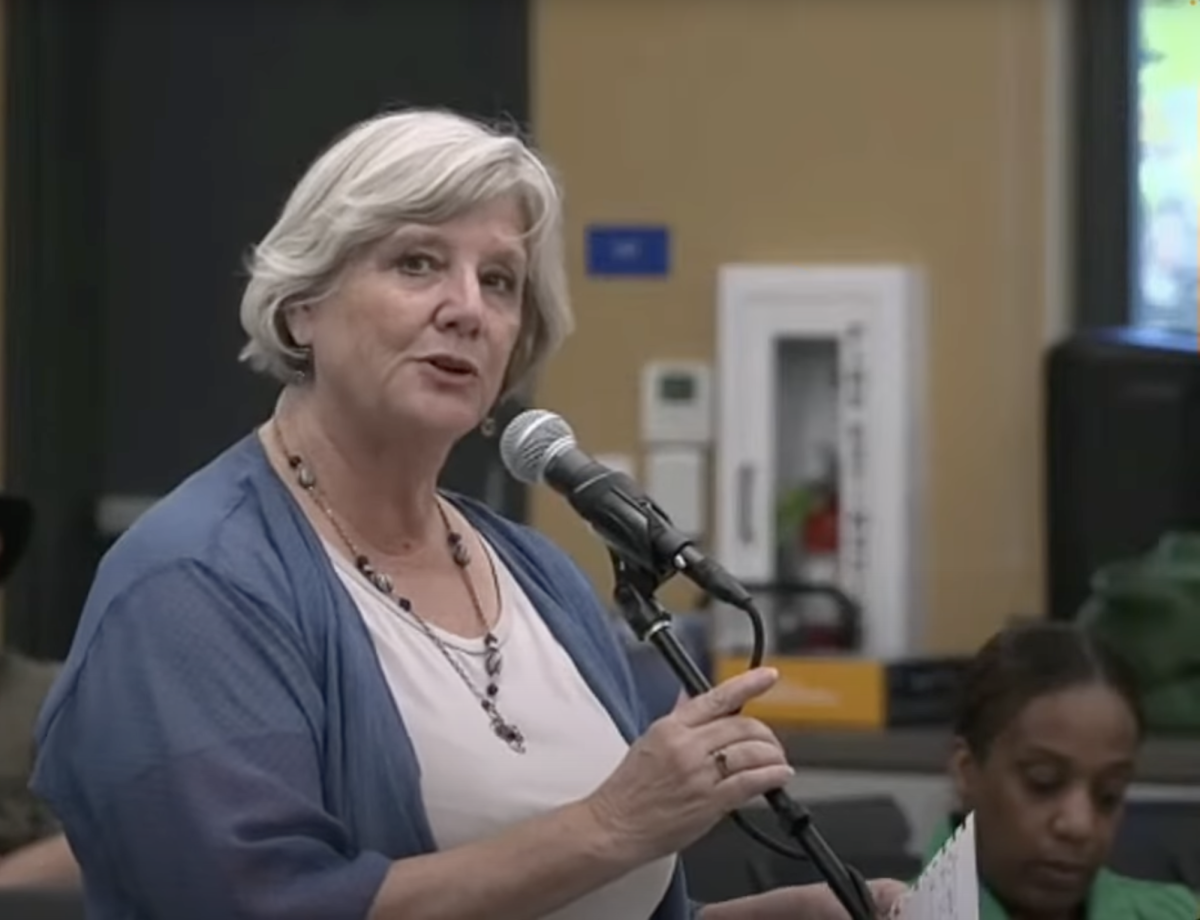

Tran was one of nearly 350 volunteers for the PITC and is Fiscal Manager of Alameda County’s Healthcare for the Homeless Program. This was her second count.

“It’s a good mission,” she said. “I just want to know what’s the reality. I want to walk the street and see how people live the homeless life.”

Tran grew up and attended college in Saigon, Vietnam before moving to Michigan to earn her MBA. Before working for the Health Care for Homeless Program, she worked as an auditor for Alameda County. She has lived in Oakland two years.

Maintaining Funds

The PITC is mandated by the federal government and conducted throughout the U.S. Its function in Alameda County is multifaceted.

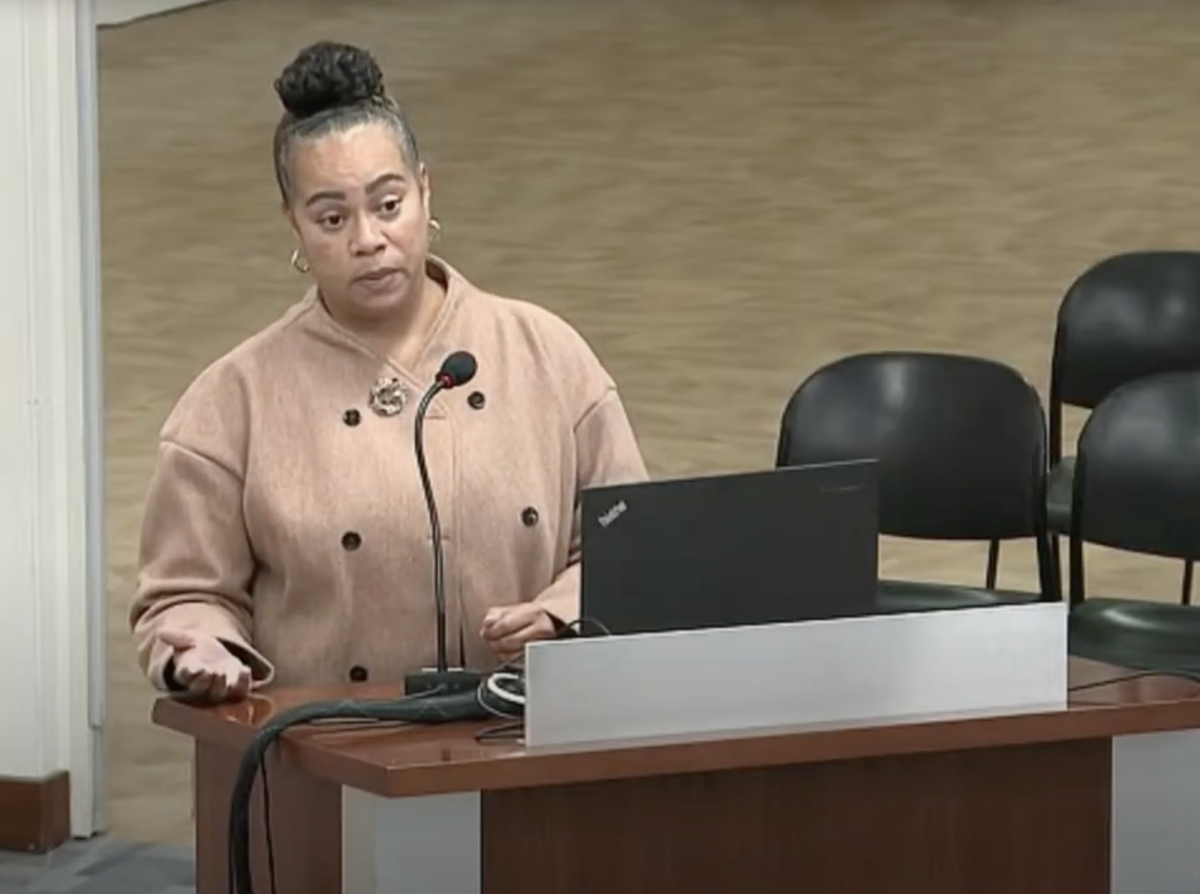

“It helps us maintain close to $40 million in federal funds for the counting each year,” said Elaine de Coligny, Executive Director of EveryOne Home. “It will help us with planning, resource allocation and strategies for how to address the problem [of homelessness].”

Other than self-perpetuation of the count, De Coligny said the homeless census will help specify which services need further funding in order to help people like Hernandez get off the street and into homes.

“First I’m gonna buy my mom a house. Then I’ll buy me a house.”

David Hernandez

Government-run programs such as homeless shelters, transitional and permanent housing organizations, and programs like Health Care for Homeless could benefit from the results of the survey.

Previous years’ counts were conducted with a method similar to data collection for election polls, with volunteers posted at common homeless resource service centers such as soup kitchens, churches, and grocery distribution points. Volunteers interviewed a core group of those who visited the center, and made assumptive conclusions based on data collected from those interviews.

“The method they used before, we know wasn’t working,” Tran said. “[The homeless population] was so underestimated.”

Whether the new blitz-count method will be more effective than the old way, said de Coligny, would be “hard to say without the data.”

Initial results from this year’s homeless census will be available in April 2017, with a conclusive report to be published by June.

Back and Forth

As the gray of morning seeps across the sky overhead, the cold has driven Hernandez and Tran into Tran’s car. Creeping between Peralta Street and San Pablo Avenue, they scan each block meticulously. As he searches, Hernandez talks about his family life.

“My mom is living on the street too,” he said.

Hernandez and his mother, Victoria Selva, live in tents near a freeway overpass next to downtown Oakland. Selva is working as a guide for the PITC as well.

Hernandez is allowed to sleep in the warehouse where he occasionally picks up work shifts, but according to him, the warehouse will soon be out of business, and he prefers to be near his mother when possible.

“I don’t like to leave her out there alone,” he said.

Home life was torn asunder when his father left Hernandez’s mother for another woman. Since then, his father ceased to be a major part of his life. Hernandez was 10 years old when his father left, and their relationship is still tumultuous.

Hernandez’s older brother is also homeless, but the siblings don’t see each other often.

“He started to do meth,” said Hernandez. “The last time I seen him, he actually took some money from my pockets.”

The young man, an East Oakland native, suffers from insomnia since becoming homeless.

“I sleep in a tent. But I really don’t sleep at night,” he said. “I don’t like sleeping in a tent, so I only go there when I’m really tired and pass out.”

Instead, Hernandez spends his nights riding his bike around Oakland’s streets or hanging out with his friends, whom he refers to as “partners.”

“Most of the time I go find trouble,” he said, listing theft as one method for making ends meet while living on the streets.

With a number of Laney students afflicted by homelessness, the reality of this city’s housing dilemma is palpable, even on campus.

—

“I steal,” Hernandez said. “Not from people. But if someone accidentally leaves a car window open or a door unlocked, I’m looking through it. I don’t care.”

Hernandez claims to have done a short stint in Santa Rita Jail for warrants resulting from unpaid tickets.

But looting cars isn’t his endgame.

“I’m actually trying to get a job at an art place,” said Hernandez, an aspiring artist who has applied for a job at local art supply stores and is currently awaiting a reply.

Assistance Needed

EveryOne Home assigned guides to neighborhoods near to where they lived in an attempt to ensure they knew the area and could assist volunteers in finding encampments that may be difficult or impossible to spot from the street.

After the count, guides were offered the opportunity to assist in a second, 14-day survey, visiting encampments to interview their fellow homeless using a questionnaire.

De Coligny hopes that the data collected from this second survey will offer a far more detailed account of the homeless population.

“This will help us understand the ways in which the [homeless] population is shifting,” she said.

Overall, de Coligny thought the count to be a success.

“We were very impressed by the swell of support from the community, and we are confident we gathered a diverse group of people for the survey this year,” she said.

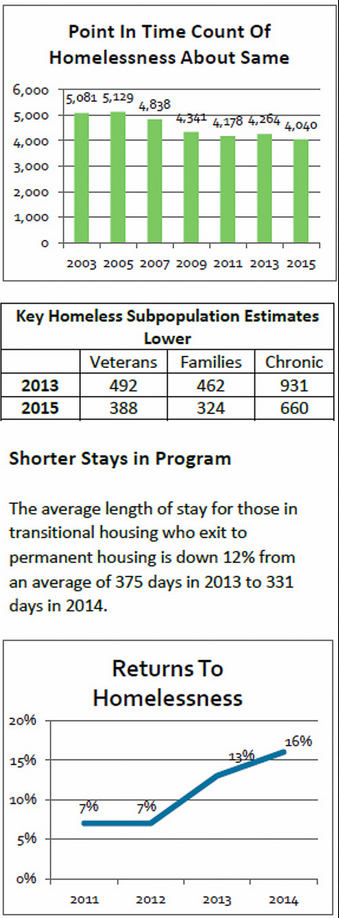

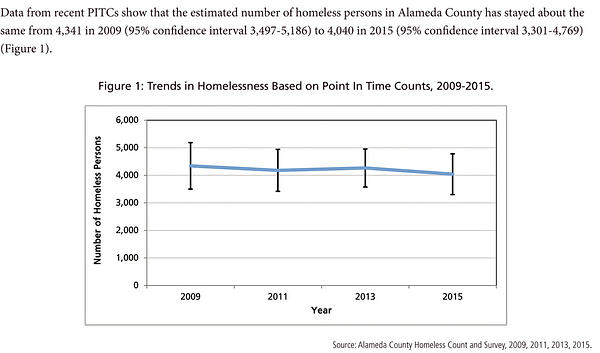

Past PITCs show that, since 2009, Alameda County’s homeless population has remained nearly unchanged (4,341 in 2003 compared to 4,040 in 2015).

However, the counts also show that the number of people moving from homelessness to temporary or permanent housing nearly doubled biennially between 2009 and 2015.

A steady homeless population in relation to the growing number of people seeking housing actually indicates a proportionately increasing homeless population, and the rise of tent cities in Oakland is starkly apparent.

In recent years, the housing crisis has seen myriad encampments materialize across the city, and finding an uninhabited overpass in Oakland is now a challenge.

With a number of Laney students afflicted by homelessness, the reality of this city’s housing dilemma is palpable, even on campus.

An Unlikely Pair

Under a crisply risen sun, Tran and Hernandez stand next to Tran’s car and make small talk.

The PITC is over; Tran and Marinez have scoured every block in their area.

The two make an unlikely pair. Tran is clean and prim, her hair pulled back in a neat ponytail. Hernandez’s pants sag, his baseball cap perched on unkempt hair. He smokes.

Tran drives a Toyota Prius. Hernandez rides a BMX bike with the paint sanded off.

Tran mentions that Jesus is her savior while Hernandez talks lightly about his childhood dog accidentally hanging himself.

But they speak easily with each other. In moments, they’re laughing. Hernandez leans casually against Tran’s Prius. Tran giggles as he tells her stories from his childhood.

The differences between the two are tangible, but — even if only for a couple of hours — they are partners in a struggle that is characteristic of Oakland.

Hernandez waits for his mother to finish her area. After turning in their count sheets and collecting their pay, son and mother will head back to their tents.

But Hernandez remains hopeful for both of them. Once he finds a job and gets back on his feet, he wants to buy a house. Or two.

“First I’m gonna buy [my mom] a house. Then I’ll buy me a house,” he said.

And for the first time that morning, he cracks a smile.

To join EveryOne Home, view the results of past PITCs, or to read this year’s PITC results when they are released in June, visit www.EveryoneHome.org.

For more information on Operation Dignity, visit www.operationdignity.org, and for more information on Applied Survey Research visit www.appliedsurveyresearch.

Brian Howey is the News Editor for the Laney Tower. Email us at thelaneytower(at)gmail.com.