Filmmakers ask ‘Who am I?’ with two documentaries

Being mixed race in America often means fielding confusing questions about one’s heritage. These questions aren’t simply answered with the name of a place, but are inherently tied up with history.

Often that history is dark, as migration often comes with stories about wars, economic or cultural hardship and what it means to be “home.”

And of course, for many, exploring those stories is necessary in order to be able to answer identity’s ultimate question, “Who am I?’

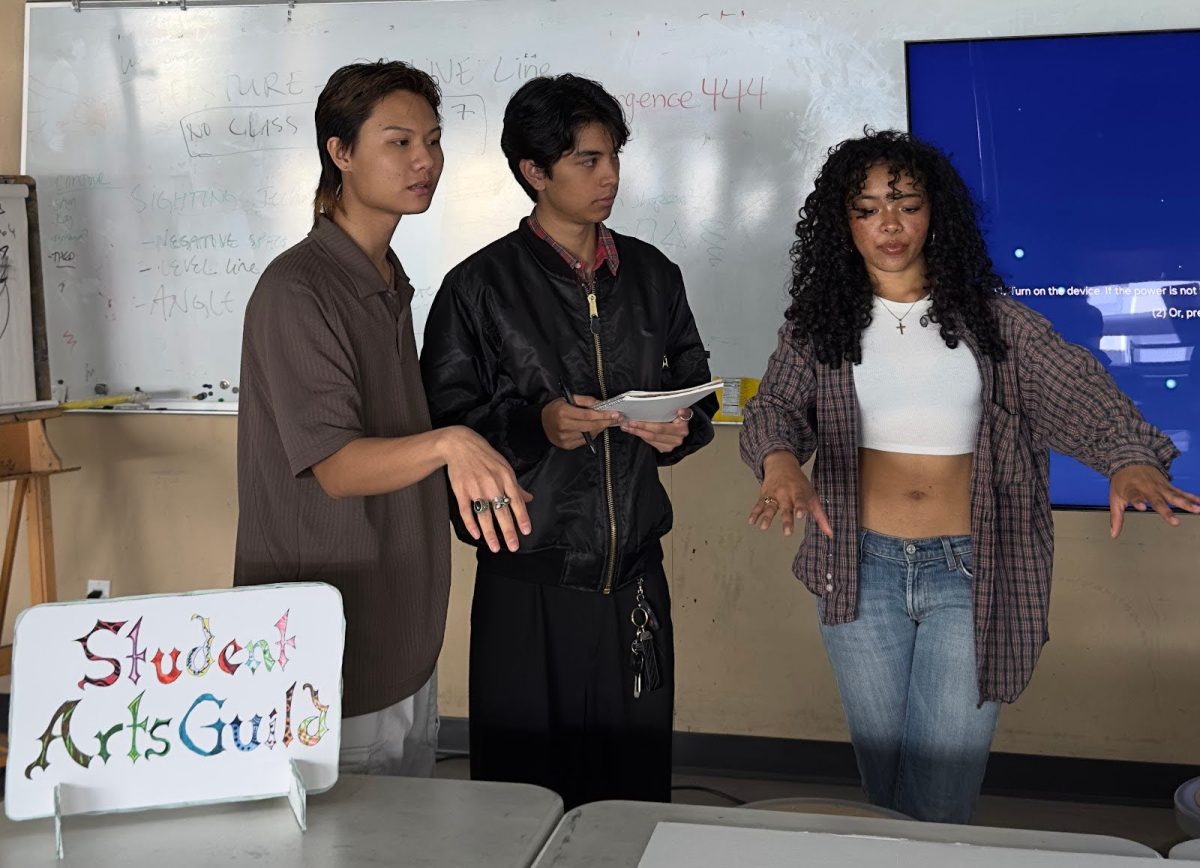

So on March 20, two filmmakers came to Laney to share their stories and their journeys of discovery. Faith Adiele and Eliaichi Kimaro screened their autobiographical documentaries at the Odell Johnson Performing Arts Center and joined English Department Chair Jackie Graves for a panel discussion titled “Mixed Roots: Mixed-Race Women Explore their African Roots.”

Both Adiele and Kimaro began with their African fathers’ pasts and ended up learning about themselves. Although the arcs of the stories parallel, the artists’ lessons learned differ in tone and focus.

Adiele’s story, part of PBS’ 2004 series “My Journey Home,” starts with her childhood, growing up in a remote suburban American town as one of the only people of African descent. Her quest is to pursue meaning in being African and being American, but not African-American.

As a young adult, Adiele searches for her father, who returned to Nigeria from America when she was a small child. Upon visiting her Nigerian family, Adiele traverses questions about family, race, culture, and belonging.  When her half-siblings were born, the after-birth was buried each time among the roots of a young fruit tree. “How do I belong to someplace I have not been planted?” Adiele wonders.

When her half-siblings were born, the after-birth was buried each time among the roots of a young fruit tree. “How do I belong to someplace I have not been planted?” Adiele wonders.

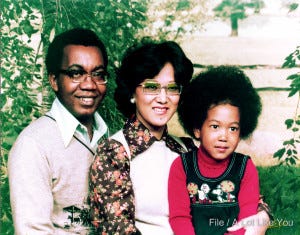

Kimaro’s film, “A Lot Like You,” was meant to document her Tanzanian father’s life, not to focus on coming to terms with her Korean-Tanzanian-American identity. But when Kimaro visits her father’s old home in Tanzania, she discovers tension, secrets and resentment among her father’s siblings rooted in the trauma of violent marriage practices.

Students who attended the screening were clearly moved by both films and applauded loudly and with melancholic sincerity before eagerly raising hands to ask questions of the filmmakers.

When a student asked about the practice of female genital mutilation and what could be done to stop this violent practice in East Africa, Kimaro encouraged audience members to find ways to “chip away at the mountain of gender violence” locally instead.

Kimaro struggles with identifying more with her aunts than with her father as a result of her own experience with being raped as a child. And until the film was released, Kimaro never told her father about her personal trauma.

When he saw the film, the two discussed it, however, and in the panel, Kimaro revealed that it helped to bridge this space between them. “This film makes us stronger as a family because there are no corners left for us to hide behind,” she remembers her father saying.

Most people with questions about their identity and cultural history will not have the chance to travel to recover lost family members but both Adiele and Kimaro hope the details in their stories help others connect and begin to own their own stories.

Graves also hopes people who have these questions will find ways to explore them. “Being mixed race is a challenge but it is also a superpower,” she said. “People project things onto you and there is a sense of constant searching. But we are more alike than different. And we all have a story to tell.”