Something for everyone at Berkeley Art Museum Pacific Film Archive

There’s more than meets the eye at the newly opened Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), on the corner of Berkeley’s Center Street and Oxford Street.

There’s more than meets the eye at the newly opened Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), on the corner of Berkeley’s Center Street and Oxford Street. In fact, the most exciting parts of the museum are what’s barely visible from the outside: intricate spiderwebs, tiny snowflakes, 16th century lace, and 25,000 square feet of gallery space, all hiding underneath its small city block footprint.

That’s why — despite its peculiar quirks, and with discounted admission available for $10 with a student ID — the BAMPFA is a museum worth getting up close and personal with.

The BAMPFA experience begins outside the two-part structure, its northern half looking like a stainless steel whale — with a TV for a face — sliding off of its more rectangular southern half.

Step inside, however, and you’ll be confronted by a cavernous interior and a huge 60 by 25-foot Art Wall, featuring a painstakingly painted mural. In ink brush, artist Qui Zhijie has created a collage of gardens from around the world — both fictional and actual. Gardens from classic Chinese literature intermingle with depictions of the San Francisco’s very own Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park. According to the museum, the mural — which will be featured on the Art Wall only temporarily — is “a vision of the world as a garden, hence its name: ‘The World Garden.’

Experiencing the world as a garden — slowly and contemplatively — is what BAMPFA has in mind: its primary exhibit, “Architecture of Life,” sprawls out through the museum’s three floors, described for visitors as “a poetic excursion” meant to “stimulate reflection on our experience of life through… structure and imagination.”

Experiencing the world as a garden — slowly and contemplatively — is what BAMPFA has in mind: its primary exhibit, “Architecture of Life,” sprawls out through the museum’s three floors, described for visitors as “a poetic excursion” meant to “stimulate reflection on our experience of life through… structure and imagination.” When the museum first opened to the public on Jan. 31, however, the museum felt less like a secret garden and more like a botanist’s acid dream.

As a DJ spun tunes from bands as eclectic as 70s new-wavers The Nerves, old-school hip-hop favorite Digable Planets, and hip house diva Azealia Banks, a group called the Anna Halpfin Dancers splayed themselves out through the gallery’s main amphitheater beneath the Art Wall — literally! Sprawled across staircases, seating areas, and the floor, the dancers gyrated while sporting tie-dyed tarps and chanting phrases like, “This is art! I am art!”

If that kind of post-modern performance isn’t your cup of tea, then some of the museum’s other offerings might not be, either. The BAMPFA features its fair share of inaccessible art: paintings of squares, for example, and one of Georgia O’Keefe’s famous abstract depictions of a door.

If that kind of post-modern performance isn’t your cup of tea, then some of the museum’s other offerings might not be, either. The BAMPFA features its fair share of inaccessible art: paintings of squares, for example, and one of Georgia O’Keefe’s famous abstract depictions of a door.But look past the typical museum fare and you’ll uncover what makes BAMPFA unique: its tiny pieces, nearly lost to the unknowing eye. At age 20, Vermont farmer Wilson Bentley became the first person to ever take a picture of a snowflake. And of the five thousand snowflake shots he took over his lifetime, a good dozen are featured on the far end of the ground floor’s gallery room — all still remarkable, despite being over a century old.

“Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated,” he wrote. “It seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others.”

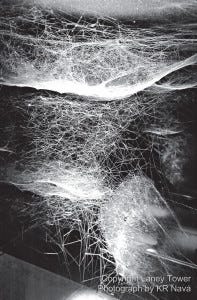

“Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated,” he wrote. “It seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others.”Those words could be used to describe another temporary mini-exhibit, located right in front of the entrance to the museum. Only allowing six people inside at a time, the small black room features nothing but four tiny — and breathtaking — spiderwebs.

Argentine architect Tomás Saraceno took groups of “social spiders” — spiders that, in nature, live separately but work together — and had them weave webs in glass boxes.

Argentine architect Tomás Saraceno took groups of “social spiders” — spiders that, in nature, live separately but work together — and had them weave webs in glass boxes. Afterwards, he introduced new species of spiders to the same box, creating unreal lattices and shapes that one would never see outside BAMPFA. Other kinds of unreal lattices are also available to examine: an exquisite collection of handmade laces and linens from the 16th century are positioned neatly below a set of magnifying glasses on the bottom floor.

And while you’re there, don’t forget to make your way to the back of this underground area. One of the museum’s more peaceful but hard to find spots is the Koret Reading Room, with hundreds of expensive art, design, and architecture books to be flipped through on a set of striking wood-carved benches, chairs, and tables.

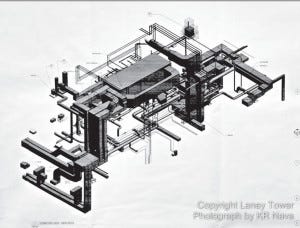

At the back of the room, you’ll also catch some of the blueprints for the building itself — an insight into the mind of the master designer who shaped your museum experience.

But in addition to celebrating the tiny — and if you couldn’t tell from the Art Wall — the BAMPFA revels in gigantitude as much as it does minuteness.

But in addition to celebrating the tiny — and if you couldn’t tell from the Art Wall — the BAMPFA revels in gigantitude as much as it does minuteness.For example, the museum couldn’t call itself a film archive without a place to show them off: a 232-seat film theatre looms large on the third floor, which will start showing off the archive’s vast collection on Feb. 5. The films of French director Maurice Pialat — under an exhibition called “Love Exists,” just in time for Valentine’s Day — will screen until March 25. Upcoming film series include an African Film Festival starting on Feb. 11.

The museum’s lower-level study centers also boast gigantic collections of films, books, journals, photographs, drawings, Asian artworks, and conceptual art materials, available for public study. The biggest, the Film Library and Study Center, is open Wednesdays through Fridays from 1 p.m. — 5 p.m., while the others are available by appointment.

BAMPFA also accommodates big groups looking for lots of fun, with its Family Fare series of events: On the second Saturday of each month, at 11:30 a.m. and 1 p.m., grown-ups and kids alike can play around in the colorful, eclectically stocked Art Lab on the basement floor after getting a family-friendly tour and discussion of the museum’s exhibits.

On Feb. 13, UC Berkeley graduate, painter, and educator Heide Miller will lead “Mapping, Mandalas, Matrices, and Me,” showing participants how to “artfully organize and map” their lives through shapes, structures, watercolors, and inks.

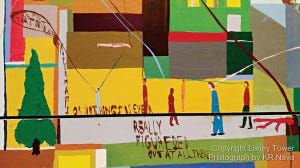

And finally, no work at the BAMPFA combines massive and miniscule like the ground floor gallery’s “Cityscape with House & Gray Energy,” one of the most dynamic and colorful works in the entire museum.

And finally, no work at the BAMPFA combines massive and miniscule like the ground floor gallery’s “Cityscape with House & Gray Energy,” one of the most dynamic and colorful works in the entire museum. “The contrasting colors and shapes are mental and vibrant with the energy of the complexity of getting and keeping it together,” creator Chris Johansen writes, summing up what it’s like to see his art.

Full of little city dwellers spread out across the sprawling canvas, each with its own mini speech bubbles, the painting — like the museum — invites you to take it all in one breath, and then dive into what each individual piece has to offer.