This year, my partner’s daughter passed away. She was not yet 40; it was sudden, unexpected, and indescribably painful for us all.

It will feel this way for a long time because the grieving process never really ends; the deaths of our loved ones are forever frozen in time. Even after we mourn, we still circle that moment — we dance with our memories of them as we remember so that those memories take on a life of their own.

“Memory is a strange thing,” Louise says at the start of “Arrival.”

We watch a flurry of her memories on-screen: scenes of Louise with her daughter, Hannah.

At first, Hannah is a happy child.

“I used to think this was the beginning of your story,” Louise says, as we watch Hannah grow up. But before she even reaches adulthood, Hannah is hospitalized, quickly becoming a terminal patient. “And this was the end,” Louise says.

By the time we’re five minutes into the movie, we see Hannah die in her mother’s arms. Louise closes her voiceover monologue: “Now I’m not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings.”

Played by Amy Adams, Louise is a brilliant linguist in a world erupting with fear after aliens arrive on Earth. The U.S. military enlists Louise to figure out why they’re here by translating their unintelligible language, made of inky circles they make with their six-fingered hands.

Louise soon discovers these rings are fully-formed sentences, which these “heptapods” say all at once, instead of choosing each word in a linear order, like we do.

For the sci-fi lover, Louise and the other characters recite neat, nerdy facts throughout the film, about linguistics and science. But they leave out one: in 2012, an economist discovered that people who speak languages without a “strong future tense” understand time differently.

For example, people who speak Finnish, German, or Mandarin cannot express the idea, “I will do this thing in the future.” They say instead, “I do this thing in the future.” The economist proved that these people plan better: they save money more often, they smoke less. They perceive the future — and the present — more sharply than we do. Because the aliens express themselves all at once — circularly, with no beginning or ending to what they say — Louise thinks they might also understand time differently: by experiencing time all at once.

Because the aliens express themselves all at once — circularly, with no beginning or ending to what they say — Louise thinks they might also understand time differently: by experiencing time all at once.

What would this feel like? Movies, sometimes, can come close to capturing such an experience — and “Moonlight,” another independent film, certainly does.

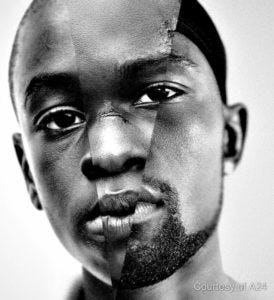

In Moonlight, we also watch a child grow: Chiron, a young Black boy from Florida. The first chapter of his story is titled “Little,” and shows him running away from a world of poverty, abuse, and fear.

Juan — a local drug dealer — tries to mentor Chiron with kindness, after he discovers the depth of Chiron’s sadness. By the end of this first chapter, we discover it too.

“What’s a faggot?” Chiron asks Juan. Carefully, Juan answers: “It’s a term people use to make gay people feel bad about themselves.”

Chiron asks him a second question: “Am I a faggot?”

“No,” Juan replies immediately. “You could be gay, but you’re not a faggot.” He explains to Chiron that he will someday learn whether he is gay, but that he doesn’t need to worry about that right now.

But in chapter 2 — titled “Chiron” — the worry is very present. A closeted teen, Chiron grieves the loss of his mentor, his relationship with his mother, and his innocence. An awful series of events lead to one of Chiron’s happiest moments, and then one of his worst. The latter leads us into the third and final chapter of his story, titled “Black.”

An awful series of events lead to one of Chiron’s happiest moments, and then one of his worst. The latter leads us into the third and final chapter of his story, titled “Black.”

Every actor in “Moonlight” brilliantly relies on tiny facial expressions to reveal deep emotions, but Trevante Rhodes is the most talented of them all, playing the adult Chiron: his movements signal maturity and confidence, but in small moments, he reminds us of the memories of childhood and adolescence that live on within Chiron.

Many films about queer youth tell similar stories: a coming of age process filled with ups and downs. But the title of the last chapter is important, because “Moonlight” centers Blackness and Black experiences. It also laments the effects of a lack of physical and emotional intimacy between men — Black, gay, or not.

We see two decades of Chiron’s life fly by in a two-hour film, but if we pay attention — and the movie’s perfect cinematography and poetic score keep us watching — we can learn what some of what it is to be Black and queer in America.

We can also learn, by watching Chiron grow, that life is not made up of single moments or neat chapters.

If we step back and see our reality — our histories, our lives and deaths — as a whole, or as a ring with no beginning or end, we discover that we are a thousand experiences, a million memories, and infinite interactions with the world around us.

We get to choose what these things mean — as Chiron and Louise do by the end of their movies — but we can make them mean so much more if we understand them in the context of the space and time around us.

It seems impossible to understand this idea. In fact, it takes an alien race to help Louise understand it in “Arrival.” More importantly, it requires she learn a brand new language. If this language exists — if we don’t wait for aliens to bring it to us — then movies like “Moonlight” and “Arrival” might be that language.

I saw both films with my partner, just months after his daughter’s passing. After “Arrival” ended, he said to me: “We needed that.” By “we,” he meant him and me.

But by “we,” he also meant the bigger “we”: humanity. By seeing and understanding films that speak in this language, we can follow Louise and Chiron in making a new future — and a new present — possible.

Categories:

Moonlight and Arrival: the movies we need

November 29, 2016

About the Contributor

In the fall of 2019, The Laney Tower rebranded as The Citizen and launched a new website. These stories were ported over from the old Laney Tower website, but byline metadata was lost in the port. However, many of these stories credit the authors in the text of the story. Some articles may also suffer from formatting issues. Future archival efforts may fix these issues.