ADLEY PENNER LIVES IN THE SHED behind the tomato plants. Its door is painted with azure streaks and golden loops. The plywood walls are warped, the plastic roof cracked. Last year’s rain took a toll on the roof, so the young musician has rigged indoor gutters to keep his bed and belongings dry.

Penner sits in a chair next to the plants, admiring the tumble-down hovel. “It’s called the ‘Shed-ri-La,’” he says, grinning.

Penner’s seven roommates share a house in West Oakland, and he saves on rent by rooming in the shed. Penner is a busker, a musician who performs in public spaces like BART trains for spare change and loose bills. He plays guitar with his friend Ibrahiim “Ibby” Freeman, who slaps a box drum called the cajón. Together, they are “Zebra Operation.”

Freeman lives a few blocks from Penner’s “Shed-ri-La,” where he shares a duplex with three roommates. His bedroom is a space partitioned from the living room by taped-together Styrofoam boards and bed sheets. It fits a small desk and mattress.

Penner and Freeman have to be creative with their living situations, but both say they’re happy. They say improvised bedrooms and skimping on amenities are normal sacrifices for Oakland artists. To them, it’s better than the alternative.

“I have a lot of friends who work six days a week, seven days a week,” Penner says. “They’re not able to focus directly on their art.”

Committed artists have brought Oakland into the spotlight as a hub of powerful and critically-minded creativity. But as high rents push living standards lower and lower, having a shed as a home or Styrofoam as a wall has become commonplace.

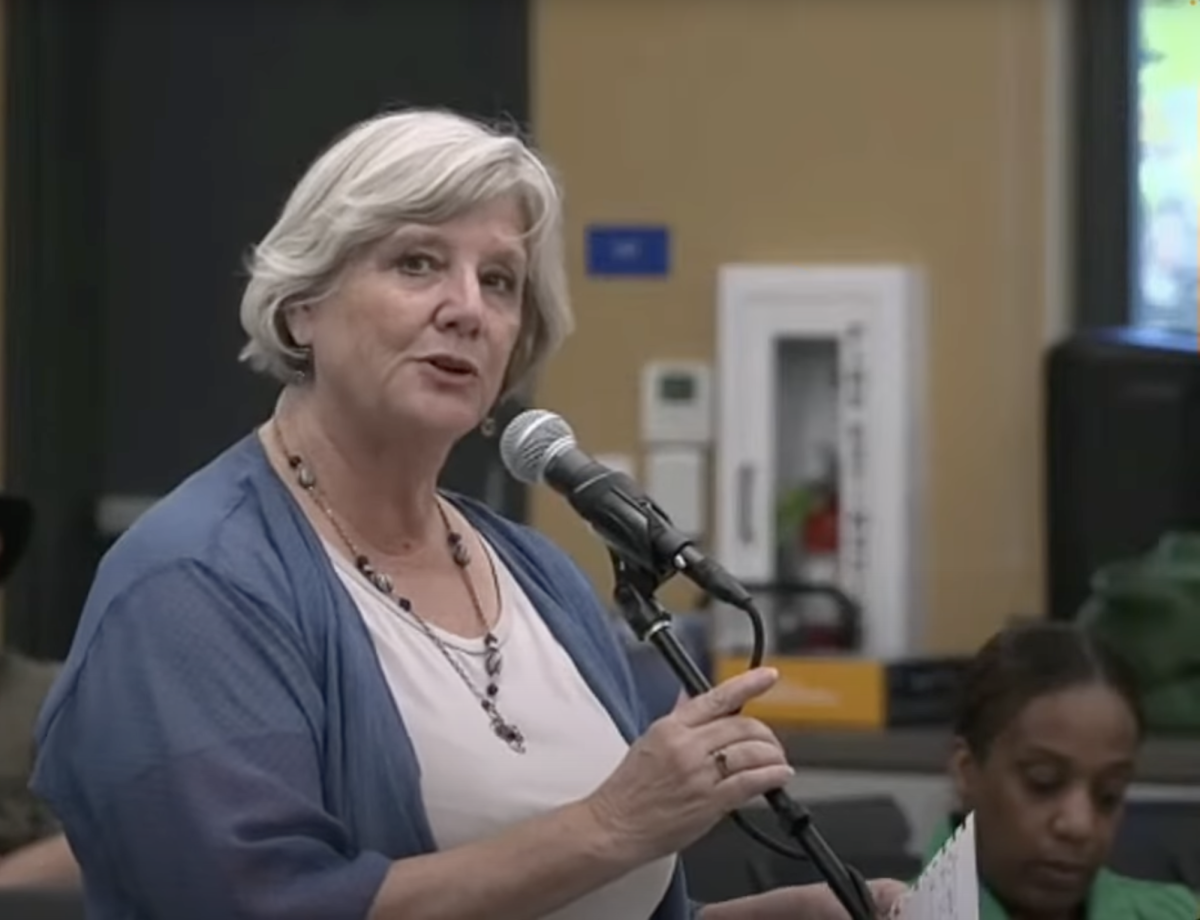

Those artists in more comfortable living situations don’t fare much better in the long-term. Hollie Hardy teaches English at Berkeley City College, runs poetry workshops at the SF Creative Writing Institute, and works for a construction company. An award-winning poet, she also helps organize Oakland literary festival Beast Crawl.

Only by holding down three jobs is she able to afford her rent-controlled, one-bedroom apartment in Oakland’s Uptown.

Hardy loves her place; it has hardwood floors and great lighting. Whole Foods is just a block away, and she can see Lake Merritt from her roof.

She’s lived there 20 years; over the past decade, she’s seen her neighborhood turn into a burgeoning hot spot for Oakland’s bar and restaurant scene.

But Hardy fears an eviction is coming, and the anxiety can be overwhelming. “There have been times when I literally couldn’t sleep at night,” she says. “I know that when they evict me — and they will do it — I will probably have to move out of Oakland.”

Her apartment complex is owned by a family working with the city to level her entire block and erect high-rise apartments, she says. To Hardy, it’s just a matter of time before she’s displaced.

Penner, Freeman, and Hardy are typical members of the Oakland arts scene, a community that has been dealt a particularly harsh series of blows over the past decade. This community may soon be uprooted by developers and the City government, if there’s no relief from the daunting cost of living in the so-called bright side of the Bay.

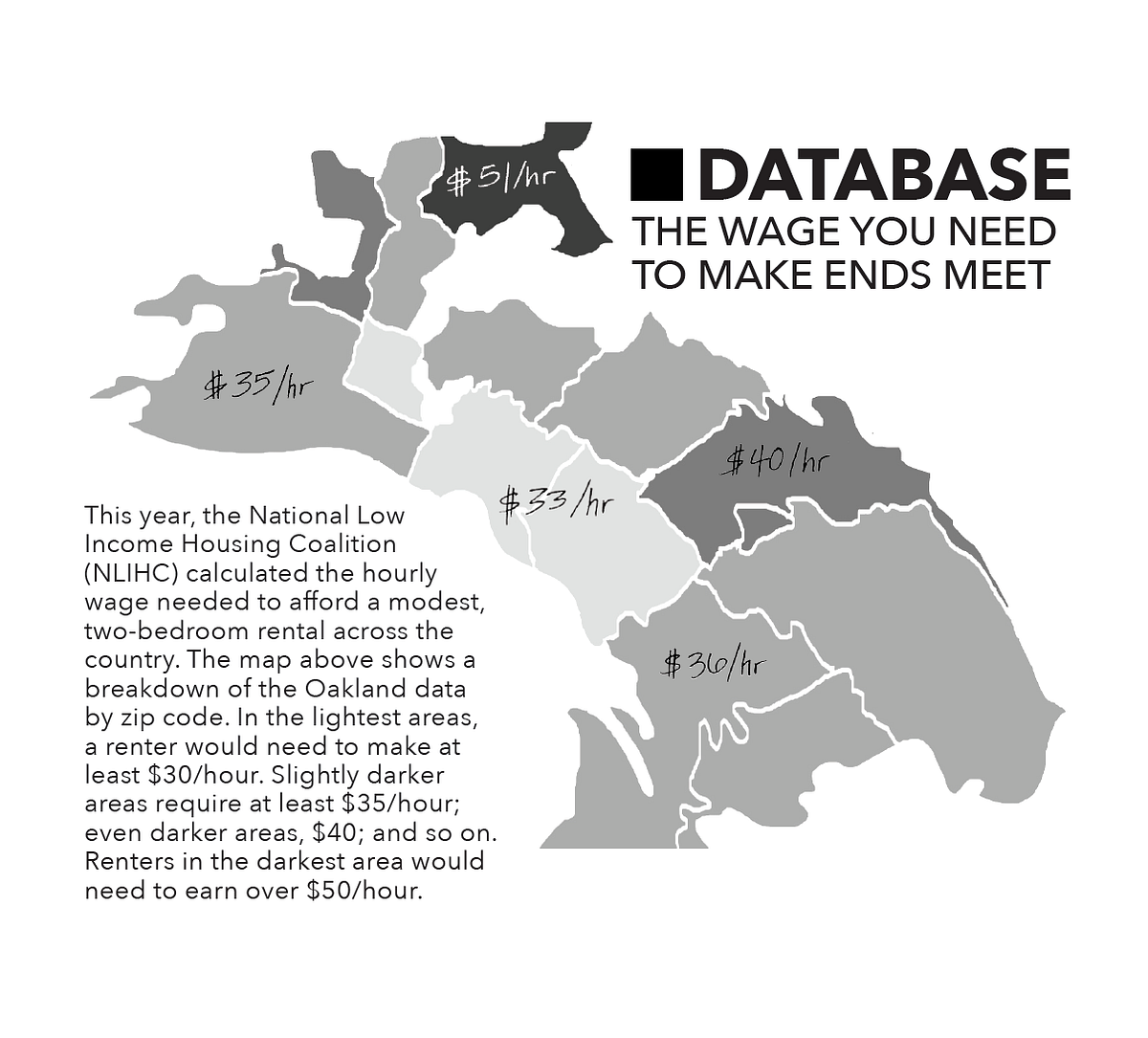

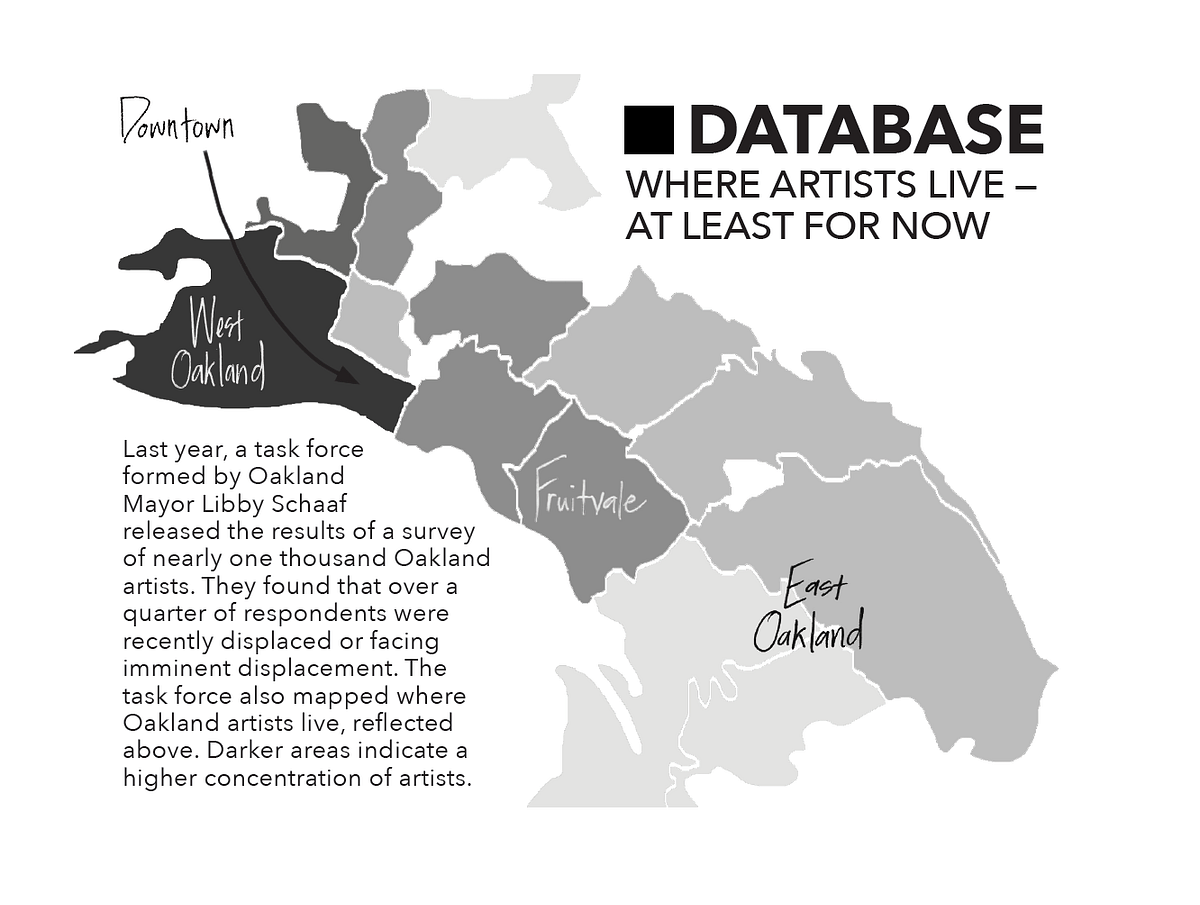

In 2016, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf’s Artist Housing and Workspace Task Force released the results of a poll of nearly one thousand artists in Oakland. A quarter of those polled had been displaced in the last year, or were currently facing displacement.

Nearly half of those being displaced were losing both their home and their work space, a majority of them forced out by rent increases. And those who live in single-family homes, like Freeman and Penner, don’t have rent protection.

Under the Costa Hawkins Rental Housing Act, single-family homes are exempt from Oakland’s Rental Adjustment Program, which limits how much a landlord can raise the price of a rental property each year. This means landlords can legally raise the rent on a home until the tenant can no longer afford to live there.

A bill that would repeal the Costa Hawkins Act was put on hold shortly after being introduced to the California state legislature this year, the Los Angeles Times reported.**

Arts spaces are feeling the squeeze, too. The impact of the tragic Ghost Ship warehouse fire is still visible. The blaze killed 36 members of Oakland’s art community in December 2016.

Artists who spoke with the Tower say that fire code crackdowns on illegal spaces have changed the underground art and music scene. “The opportunity to play shows and to have these different underground events just got decimated,” Freeman says.

He and Penner have other bands that regularly performed in some of these spaces. Freeman says the illegal venues that survived the crackdown are being discreet. He didn’t want to name any, fearing they could be subject to code inspection and subsequent eviction should they be discovered by the city.

Commercial renters don’t get a break either. There’s no rent control for commercial spaces, nor are tenants legally entitled to a maintained property, according to California state law. Shutdowns of galleries and collective spaces are now common in Oakland.

Affordable spaces are rare.

The crisis is emblematic — and in part, a result — of the country deprioritizing art. The U.S. spends far less on public arts funding than, for example, many European countries.

In fact, America invests less than 30 times what the average European Union country does. Only 0.02 percent of U.S. public spending goes towards funding arts and culture, for organizations like the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for Humanities, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

And although this funding is already tiny, current U.S. President Donald Trump’s budget proposal for the upcoming fiscal year suggests privatizing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and eliminating the other programs entirely.

At the state level, the situation isn’t much better. Last year, California landed in the bottom five states for per capita arts funding, according to the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies.

In Oakland, that trend continues. In a detailed breakdown of Mayor Schaaf’s proposed budget for the next two years, less than a third of a percent of the General Fund would go to its primary arts and culture departments — combined.

Almost 150 times that — or, a whopping 44 percent of the General Fund— would go to the Oakland Police Department, according to Open Budget Oakland.

Mayor Schaaf’s budget proposal also indicates that she would hire at least 11 more employees at the Department of Planning and Building to speed up development. And while the budget includes a three percent increase for homeless services, there is no funding listed for affordable housing.

Challenges and stressors in Oakland are multiplying for artists as the city scrambles to accommodate an influx of developers, tech employees, and other affluent transplants.

Without the right kind of help, Oakland could lose yet another piece of its vibrant, artistic legacy.

JULIUS G. KELLERSBERGER FELL IN LOVE with Oakland before The Town was even a town. In 1852, the ambitious and creative Kellersberger cast his gaze over a rich, fertile California sprawl, and birthed a city on a hill.

He saw promise in the rich, bustling forests to the east and clear, blue waters to the north and west; he drew inspiration from the buzz in the already thriving harbor town just across the bay. Gold had brought him and his wife, Caroline, to California, but in Oakland, Kellersberger had found a very different kind of treasure.

Kellersberger, a Swiss engineer hired to survey the city of Oakland, drew from the wilderness a well-designed grid with Broadway down its middle. He plucked from his head other now-familiar names — Webster, Clay, Castro, and Harrison — to fill out one axis of that grid, then laid numbered streets perpendicularly down towards the water in a neat cross-hatch.

Across the tableau he evenly peppered public squares, modern agoras where Oaklanders could congregate and inspire one another.

City planning, at the time, was an art, and Kellersberger had a grand vision. He set aside four entire blocks for the prestigious college preparatory school College of California, what could have been Oakland’s intellectual center. (Less than two decades later, the school became a university and got poached by the city next door. We know it now as the University of California, Berkeley.)

A few years later, he gave the City its Market Street, hoping that, as in San Francisco, Oaklanders would give their neighborhoods personalities: “East of Market” and “West of Market.” And two blocks northwest of what is now Laney College, he gave his treasured town a personal touch: Caroline Square, his wife as namesake, still exists, now going by the name Madison Square.

The careful beauty Kellersberger had arranged, however, soon became a threat to its survival. It was too efficient to build in his well-organized city: developers were flooding Oakland, fighting over space. They disregarded the town squares Kellersberger had created and built wherever they pleased. California bungalows suddenly spread like wildfire across the city; the population skyrocketed.

By the time Kellersberger fled the state in 1857, Oakland was already yet another overcrowded California city.

Today, Oaklanders endure impoverished living conditions, a lack of affordable housing, and threats of eviction that are always looming on the horizon. They mourn the demise of the Art Murmur, the tragedy of Ghost Ship, and the cultural annihilation of neighborhood after neighborhood for the sake of “beautification” and “economic development.”

The history of Oakland tells us this is nothing new.

Since an imagined map became reality during the tenure of Julius G. Kellersberger, Oakland neighborhoods have organically risen and dramatically fallen at the whims of local and federal disinvestment, deeply rooted discrimination, and developers uninterested in taking the city’s history seriously.

Oaklanders, if they’re to have a bigger say in their city’s future, can’t afford to make the same mistake.

The City called it “urban renewal,” when Kellersberger’s work finally began to crumble. It was 1954, and a half-century of volatile development had shaken Oakland out of its roots.

Across the bay, the influential Arts and Crafts Movement had bloomed through the first quarter of the 1900s in a commercially diverse San Francisco. Meanwhile, Oakland had become a cold, stark factory town.

Industrial jobs abounded, but at the price of aesthetics: gray factories, workshops, and warehouses defined the look and feel of Oakland through the 1930s.

But the World Wars — especially WWII — changed the color of Oakland. Tens of thousands of Black Americans migrated to the East Bay over the next two decades, bringing a brand new sound with them.

The harsh discord of metal and steel gave way to deeply felt blues, R&B, and gospel music, echoing through the streets of Black Oakland. The City’s labor union for professional musicians explicitly barred Black artists from playing in Downtown Oakland, so Black Oaklanders formed their own musical haven on 7th Street.

Nat King Cole, B.B. King, Aretha Franklin, and Duke Ellington made their way to and through the area’s newly spawned Sweet’s Ballroom, California Hotel, and Slim Jenkins’. And, of course, one of the many newly settled West Oaklanders was the patron saint of literary sound herself, Maya Angelou.

The West Oakland renaissance of the 1940s portended a new future for the city. By then, the Arts and Crafts Movement had finally landed in the city with the relocation of the California College of Arts and Crafts from Berkeley to the corner of College and Broadway — we know it now as California College of the Arts (CCA), this Oakland campus intact.

But the City’s focus was not on supporting a booming arts scene. Instead, the City started targeting the people who had made the scene possible.

During WWII, housing became so tight that the federal government had had to step in, building 30,000 homes in the East Bay, attempting to accommodate over 90,000 workers.

But the Federal Housing Administration also enforced strict racial covenants that had, by 1950, pushed 80 percent of the city’s Black population into West Oakland.

As the neighborhood became more crowded — and consequently, more run-down, more violent — the City declared war on these non-white neighborhoods in the name of that “urban renewal.”

Tens of thousands of Black Americans — the same ones that had been drawn there just years before, the same folks who’d enriched the city and its legacy — were aggressively displaced, their homes destroyed, and the cultural institutions they’d built shattered.

The dream of 7th Street was over.

Kellersberger’s dream of a unified Oakland was over, too. In 1955, despite a fierce fight from the city’s most marginalized populations, the I-880 toppled into place, demolishing hundreds of homes, slicing the city in two, and isolating its center from its jewel — the waterfront.

A few decades later, the construction of I-980 officially destroyed the connection between West Oakland and the center of town.

Oakland became as segmented as the East Bay itself, by then simply a series of disparate satellite cities orbiting San Francisco.

The 1980s and ’90s were a free-for-all in Oakland. A sense of lawlessness had spread across the city, by then known as one of the most dangerous places in America.

In East Oakland, drug lord Felix Mitchell’s gang-controlled kingdom prospered, the first in the country of its size. Crack cocaine, as it did in many U.S. cities, reigned high.

Taking advantage — or in spite — of the Oakland Police Department’s focus on gang- and drug-related crimes, the underground Oakland arts scene grew and thrived.

Warehouses like the Sauce Room hosted illegal after-hours shows, where nights ended long past last call. Sideshows — think unsanctioned car shows, with stunts — sprang up at the Eastmont Mall and Foothill Square in East Oakland, and soon became a city staple.

Across genres and mediums, new art hubs popped onto the scene: the era saw Oakland gain jazz club Escovedo’s on Lakeshore, rock venue The Omni on Shattuck, hip-hop-centric Sweet Jimmie’s (now the New Parish), experimental music joint Koncepts Cultural Gallery by Jack London Square, and a branch of landmark Black bookstore Marcus Books on Martin Luther King Jr. Way.

Over in East Oakland, at the Mystik Journeymen’s legendary hotspot 4001, dozens of underground rap and hip-hop artists came out to what the Journeymen called “Top Ramen parties.”

Price of admission was either a few bucks or a helping of the party’s namesake.

Back then, SFers who wanted to be out until the early morning ventured to Oakland for their fix.

As the ’90s rolled around, some San Franciscans were already feeling the effects of the dot-com boom: more affluent techies meant more policing of nightlife.

Oakland house shows and warehouse parties filled the void.

And as the century drew to a close, Oakland gave birth to a slew of legendary artists: hip-hop greats Tupac Shakur, MC Hammer, and Too $hort.

The story goes, or so they say, that it wasn’t until San Francisco artists were priced out and pushed into Oakland that Oakland got its arts renaissance. Oaklanders would disagree: The town always brought the noise.

But behind the music, the stage had been set for the coming housing crisis.

In 1978, under the first governorship of Jerry Brown, the “People’s Initiative to Limit Property Taxation” found its way onto the state ballot. When it passed, the proposition sliced the property tax in the state threefold, to just 1 percent.

It also redefined future property tax calculations: as the value of a home increased, the property tax would not.

A 2016 Salon analysis of the proposition’s long-term effects concluded that it encouraged “land banking,” the practice of holding onto land you don’t need or aren’t using, since buying up new land would reset your property tax.

Oakland writer Paul Corman-Roberts lived a few blocks from Laney College in the ’90s, when the land banking became unignorable.

“I used to wander around the neighborhood,” he says, “looking at all the empty space on the streets — especially on 15th St., 17th St., Broadway, Telegraph — and going, ‘You know, this [has] a lot of potential.’”

Many were thinking the same thing.

As the new millennium was dawning over Oakland, it was setting on San Francisco. Pushed to a breaking point by ballooning costs of living, The City’s artists were migrating to The Town.

There, they saw potential in the empty lots and spaces that were only a memory in San Francisco. Intrepid Oaklanders seeking to improve their long-disinvested communities felt the same way.

And with each space was a land banking owner tired of waiting for some kind of miracle to enrich the worn streets — as well as their own pockets.

“It wasn’t a huge vision to create an arts district,” one property manager said in 2014, looking back on his role in the development of Oakland’s Uptown. “It was just, ‘How do I rent these apartments in a not-so-great neighborhood?’”

Nevertheless, it was a match: New galleries, music venues, and arts spaces spread across the area in rapid succession, bolstered by cheap rent and a sudden interest by the City government in this little miracle.

Soon, a grassroots movement to unify the Downtown arts community was born: the Oakland Art Murmur. First Fridays followed, loosely organized by Murmur galleries, bringing together a collection of Oakland’s freshest, weirdest artists to take over Telegraph Ave. once a month.

Both were emblematic of the new critical mass of art in the city — and the nation was taking note.

From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, over 130 print articles nationwide reported on a revitalizing Oakland. By 2006, the Art Murmur was mentioned in at least one major Bay Area newspaper per month.

And by 2012, Oakland had arrived: the New York Times put the town on its yearly list of 45 must-visits around the world. Oakland came in at #5, sitting proudly, if precariously, between London (#4) and Tokyo (#6).

A diverse and wildly inventive group of creatives had made Oakland hip, cool, and a place worth taking seriously.

For a brief moment, it seemed, artists had triumphed.

Jerry Brown strutted into Oakland in 1999 a mayor with a governorship already under his belt. How hard could it be to run a city when you’ve already run a state?

In his first year as mayor, Brown announced a wildly ambitious “10K Plan.” He promised to bring 10,000 new residents to the city over the next ten years, and immediately began eliminating single-room occupancy buildings, replacing them with market-rate and affordable housing.

If you build it, he assumed, they will come.

But Brown was dealing with a city shaped — and corroded — by the then-two-decades-old Proposition 13. Across the state, Redevelopment Agencies (RDAs), including Oakland’s, had borrowed massive amounts of money, betting that the change in property tax law would guarantee future revenue streams.

The gambles backfired.

Of the 10,000 Brown expected, only 5,000 new residents had arrived by 2009, leaving hundreds of new homes that had been shoved through the development pipeline empty. Across the state, RDAs had borrowed large amounts of money to make projects like the 10k Plan happen, betting dangerously against future revenue streams.

And when financial crisis and the housing crash hit, cities like Oakland, counting on big growth spurts, found themselves drowning in massive debts.

In 2012, the same year Oakland made its mark in the New York Times, Brown — by then the governor again — shut down 425 RDAs across the state.

Along with Oakland’s RDA went its Cultural Affairs Commission, another casualty of the city’s budget deficit.

By 2015, arts representation in city government had been whittled down to one full-time staffer and an all-volunteer advisory committee.

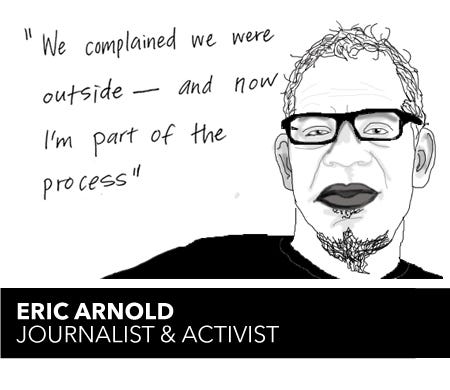

“There was no one in city government to really advocate for the arts,” prolific Oakland music journalist Arnold says, “and as a result, the arts really got marginalized.”

Oaklanders weren’t going to stand for that.

Arnold helped found Artivist PAC, working alongside Betti Ono Gallery’s Anyka Barber, Sole Space’s Jeff Perlstein, Impact Hub Oakland’s Ashara Ekundayo, internationally recognized Oakland artist Favianna Rodriguez.

“We created a platform around the cultural arts and advocated for more investment,” says Arnold. He and his comrades wanted to maintain cultural diversity in Oakland, and believed cultural zoning and the protection of existing art spaces was the answer, not gentrification.

The City, he felt, disagreed.

“‘How are we going to protect low-income residents?’” Arnold asks rhetorically, mimicking the city. “’We don’t have a plan for that, and so I guess we’re gonna fast-track development.’”

Artivist PAC aimed to change that, bringing together a collection of artists committed to keeping Oakland creative.

That eventually became the mantra (and hashtag, #keepoaklandcreative) of Artivist PAC’s successor, Oakland Creative Neighborhood Coalition, still going strong today.

The coalition faces a critical turning point in Oakland’s history. Just as the difficult 1950s in West Oakland contrasted starkly with the bold 1930s and ’40s, across the city, the 2010s are turning out to be a tragic reversal of the decades prior.

The Sauce Room, Escovedo’s, The Omni, Koncepts Cultural Gallery: all gone.

The Mystik Journeymen’s old haunt at 4001 San Leandro Ave. is now home to an overcrowded live-work arts space, not so different from Ghost Ship and the many places like it.

An early casualty, the Noodle Factory, seemed to be rising from the ashes in 2008, when the Northern California Land Trust purchased their space in order to build affordable artist housing, in cooperation with the Factory. But by 2010, the housing crash had bankrupted the trust, and the property was foreclosed.

In 2011, Oakland’s Marcus Books almost folded when its owners fell prey to a Ponzi scheme, at a time when book sales were already hurting due to the declining Black population in the city.

As for the architects of the Art Murmur: in 2010, 21 Grand received a “cease and desist cabaret activity” notice from the city, ultimately forcing them to shut down. Five years later, Rock Paper Scissors, another founder, had to close its doors, too. And last May, the residents of famed San Pablo Ave.’s Ghost Town Gallery lost a legal battle with their landlord, and were forced to leave.

“These were all spaces where artist communities were thriving. And when you close down those spaces,” Arnold says, “you’re pushing people into illegal spaces.”

Arnold sees this crisis as caused by the City’s lack of a long-term vision. When the Artivist PAC was born, there was no Downtown Oakland Specific Plan — the City’s new initiative to work with community members to shape the long-term future of the area — and the only major change on the horizon to the City’s relationship with art was a small modification to the City’s Percent for Art Ordinance.

The change to the ordinance would have required developers in Oakland working with commercial buildings larger than 2,000 sq. ft. to set aside one percent of their construction budget to acquire and install public art on their site.

But the City’s skeleton arts staff meant the only input on that new provision was the all-volunteer advisory committee.

“They didn’t try to develop the best possible ordinance from a cultural arts perspective,” Arnold says, criticizing the committee’s lack of community outreach.

It didn’t matter. Less than a year later, a coalition of 300 builders, contractors, and other development industry members filed a lawsuit against the City of Oakland, claiming the ordinance violated their First and Fifth Amendments right to free speech and uncompensated seizure of land.

The City “tried to make it as friendly to developers as possible,” Arnold says, “and they got sued anyways.”

Two years later, the case pitting developers against Oakland is still in the pre-trial stage.

Outside the courtroom, it’s already clear who’s won.

THEO WILLIAMS AND HIS GROUP, SAMBAFUNK!, began drumming at 7 p.m., to celebrate a rare lunar eclipse on a Sunday night in September 2015. After about 90 minutes of drumming, a man stormed up, asking if they had a permit.

As Williams told the East Bay Express, after he did not stop drumming, the man grabbed Williams’ wrists and removed the drumsticks from his hands, and then threatened to call the police if he did not stop drumming.

The man did call the police, which prompted about a dozen OPD officers to arrive on the scene, and although the drummers were already done for the night, multiple citations were issued.

The line between legal and illegal is a blurry one for artists. There have always been noise ordinances in effect around Lake Merritt, but they were rarely enforced. Boisterous music was a hallmark of the lake: an attraction, rather than a repulsion, for locals.

No longer. New Oaklanders want something longtime locals aren’t willing to offer: their silence.

A month after the Sambafunk! incident, the Pleasant Grove Baptist Church in West Oakland found itself facing that demand, too.

The 65-year-old church has, for decades, hosted predominantly Black worshipers, engaging in what they call “joyful noise.”

Nevertheless, neighbors raised formal noise complaints against it. The city issued the church a letter threatening an initial fine of over $3000, and penalty fines of $500 per day until the noise was abated.

Sambafunk!’s Williams thinks race is a motivator when it comes to noise complaints. He doesn’t believe he and his fellow drummers were treated fairly, by the police or by the man who called them.

“He’s coming here and flexing his white privilege,” Williams said of the latter in an interview with the Express. And from his perspective, the police “are supporting that with the way [they’re] responding.”

Artists might still toe that blurry line of legality, but for Black artists, the city had made that line sharp and severe.

In April 2017, Sam Lefebvre of the Express reported on a well-known but poorly publicized secret in the city: for years, the Oakland Police Department had been blatantly discriminating against Black musicians, specifically rap and hip-hop artists, when it came to their ability to play legally in Oakland venues.

“The rap shows in question are legitimate concerts,” Lefebvre wrote, citing incidents faced by acclaimed Oakland rappers Philthy Rich, Birch Boy Barie, Project Poppa, and even now-50-year-old Too $hort, among others. These artists were prevented from performing due to last-minute pressure from OPD’s Special Events Unit (SEU), the SEU’s sudden and unaffordable reassessment of the required security fees, or outright denial of permission to play.

“And while Oakland city code requires police to provide written explanations for denying special-event applications,” Lefebvre continued in the Express, “venue owners say they’ve never been offered such documents, and police nightlife overseers declined to be interviewed for this article.”

According to Lefebvre’s research, municipal code also says that if venues use outside promoters, they have to get a special events permit from the SEU.

“I would challenge you to find a venue that doesn’t use outside promoters, and a lot of them explicitly advertise that,” Lefebvre said in an interview with the Tower, referring to venues like the New Parish or the Starline Social Club, “but they don’t get hassled for special events permits. [Only] requiring special events permits from rap/hip-hop shows is discriminatory.”

The SEU is conspicuously opaque about how it decides when to deny permits or what security fees it will levy. But a source within the City of Oakland says that, based on formal conversations with members of the SEU, they primarily Google the artist and see what’s been written about them and their entourage. (The source agreed to be interviewed on condition of anonymity.)

“The thing that strikes me as problematic,” the source wrote in an email, “is that whatever information they find on the Internet (and pretty much every flavor of information about a given thing can be found online) it’s being filtered through the subjectivity of an Oakland police officer.”

What no one else working for the City will admit, the source says, “is that genre functions as a rough proxy for race and class in ways that remain in-bounds of civil rights laws.”

But perhaps not for long: John Hamasaki and Dan Siegel, attorneys quoted in Lefebvre’s article, implied that the discrimination was ripe for a civil rights lawsuit.

Lefebvre also quoted Hamasaki as saying that that kind of anti-Black discrimination “prevents people from making a living through their art.”

But Zebra Operation’s Ibrahiim Freeman won’t let obstacles like that stop him from doing so. As a busker, he faces the risk of BART police’s reaction to him playing without a permit.

“If you stay calm — calmer than the police, and don’t let them like piss you off,” he says, “then you can usually end it without them giving you a ticket.”

He says he and his counterpart have been stopped at least five times in the last few years while busking on BART, but their only citation was for fare evasion: Penner didn’t have the right ticket.

Freeman believes it helps that they’ve got talent on their side. “If you don’t suck,” he says, “then there’s way less of a chance that you’re gonna have the cops called on you.”

But the difference between the experience of Freeman, a self-described avant-garde space-funk musician, and the experiences of the rap and hip-hop artists in Lefebvre’s story support Lefebvre’s point.

Artists in different genres, catering to different demographics, operating in different spaces, face dramatically different fates.

Spelled out in cursive using fluorescent red thread, the phrase “Culture over everything” calls out from the northwestern wall of West Oakland’s Alena Museum. The space has an unshowy charm; planks of wood and shades of green, brown and black fill out the industrial interior, its surfaces showcasing art of the African Diaspora.

It’s the early evening of June 30, and a small group of folks are here to learn how to save their own spaces, courtesy of the Community Arts Stabilization Trust (CAST). The workshop is part of CAST’s Keeping Space – Oakland, a program that might spell salvation for some arts organizations — while leaving others behind.

Across the floor, a dozen people are scattered across a casually arranged set of couches and folding chairs. They listen raptly to Tyese Wortham, CAST’s program manager, as she talks.

“Real estate is no joke,” she declares early on, a Powerpoint presentation projected behind her, filled with densely bullet-pointed slides about the Keeping Space program.

This workshop is meant to inform attendees how to properly fill out the long and documentation-heavy application, and is one of several planned throughout 2017 for the second round of grant awarding.

But only about half of the people in the room are actually there to apply for the grant. The rest are CAST members, ready to answer the multitude of questions the attendees have.

The specifics of Keeping Space take time to parse. It’s not affordable housing for artists, nor direct grants to be used at will by arts organizations. It’s a technical and financial assistance program for arts organizations already working on or seeking real estate transactions.

It does provide financial assistance for things like rent or maintenance, as well as funding to make the potential or ongoing land transactions possible. But when it comes to the latter, Keeping Space mostly holds your hand on the way to the bank.

CAST’s success in San Francisco and their time-tested financial fitness is supposed to give the arts organization in question some extra cred in their appeal to a lender by having CAST at their side. This would give economically sustainable and profitable enterprises a leg up; CAST, and its reputation, is as much at the mercy of a lender as the arts organization itself.

“At first, I was really turned off by the program,” Gina Goldblatt says. Goldblatt runs Liminal, a self-described “simple space” for writing workshops focused on female and gender-non-conforming writers, based in East Oakland, an artist-rich area where few arts grants land — including those from Keeping Space.

It turned out that, due to a grave misevaluation of the financial landscape in Oakland, the first round of grants went only to primarily English-speaking organizations in West or North Oakland. And Oakland staples like Rock Paper Scissors (RPS), which expected to meet the program’s criteria perfectly, missed the boat entirely.

Kristi Holohan, an RPS director, submitted the Keeping Space application only to find out RPS wouldn’t even be considered. “They’re like ‘Actually, you don’t qualify,’” she says, “and I was like, ‘Damn it! I just spent forty hours writing this frickin’ shit!’”

The results forced CAST to revamp Keeping Space’s guidelines to accurately reflect the community it was meant to serve. It may or may not lead to a more diverse range of recipients when the winners of this second round of grants are announced in the fall. (For more information, visit the CAST website here. The application deadline for this second round is Aug. 3, 2017.)

Goldblatt’s Liminal won’t be one of those winners. In June of this year, she found out, after six months of attending Keeping Space workshops, that she also couldn’t apply for any of the grants. Like many artists in Oakland, Goldblatt lives where she works — disqualifying her outright.

“I’m disappointed by the focus on commercial real estate because so many people are not there yet,” she says, “but for the ones that are there… you know, there’s people at every level, and they all need help.”

Ultimately, Goldblatt came around. She thinks CAST is “doing a lot of really good work.”

As for what the City of Oakland is doing: “I think it’s pretty disgusting,” she says. “They could be doing a lot better. We have a lot of private sources of funding, a lot of big donors, but Oakland is a very unique situation, and there’s a lot of people, and certain artists and areas are prioritized over others.”

Goldblatt admits that it’s a blessing that developers have, so far, ignored her part of Oakland, but hates that “people say, ‘Oh, it’s East Oakland,’ but there’s so many artists here just trying to survive.”

Pro Arts Gallery, located at the center of Downtown, did receive assistance from Keeping Space, and still, its executive director, Natalia Mount, echoes Goldblatt.

“The City could do so much more instead of just mouth-piecing that the arts are supported,” she said.

Pro Arts itself, however, might be the perfect example of mouth-piecing. Pro Arts’ building is owned by the City, who has been offering Pro Arts space, rent-free.

No more. In an interview with the East Bay Express, Mount said that even if the City offers them a below-market rate, Pro Arts will still be strained by the new expense.

In other words, through CAST, the City has helped provide anti-displacement assistance to the very organization it might displace.

Mount doesn’t think this is hypocritical.

“I think the City is being quite consistent,” she says. “The City likes the presence of art and artists. They just don’t have enough the money to pay for them out of the City budget.” After all, the $1.7 million Keeping Space is offering comes from private donors, not the City.

Like the creatives who revived Oakland’s artistic soul around the turn of the century, Mount sees reclaiming unused buildings scattered across the city as a potential solution. “They should just be given for free to artists and arts organizations as a home,” she says, “because the art is what brought people to Oakland.”

Her idea might not be too far off the mark. In 2015, Libby Schaaf assembled a Mayor’s Artist Housing and Workspace Task Force; last year, she released the task force’s findings, along with its recommendations for the City. One of these was bringing CAST’s Keeping Space program to Oakland. Another is more or less what Mount envisions, but with a twist one might have come to expect from the City.

This strategy would involve taking retail spaces that are vacant or early in the development process and handing them over to individual artists or arts organizations, until the original owner of the space goes through the months-long approval process for a land use project — at which point, of course, the artists would get booted out.

The strategy is based on the relationship between San Francisco real estate development company Build Inc. and arts organization ArtSpan. While waiting for approval to develop at their Journal Building site, Build Inc. leased an old office building on-site to 22 artists as studio space.

Artists apply for temporary residencies in the building, for somewhere between nine months and two years. In exchange for giving these artists affordable work spaces, Build Inc. benefits from the “activity and vitality in the short-term on its property,” which would otherwise go unused.

In other words, artists — and the cultural capital they provide — are now for rent in San Francisco.

And soon, perhaps in Oakland, too.

When the first GREATR GUD™ Center opened in our town, no one seemed to mind. Really, we hardly even noticed.

The place itself was wholly unremarkable, hiding there in our blind-spot, a small, pretty weed whose poisoned roots, it turns out, were already firmly anchored in our soil.

Centers had started popping up like toxic daffodils in all the other neighborhoods, their popularity unsurprisingly increased by all the publicity from the protests. Soon our whole town and many others were powered by the energy gathered at the Centers. Politicians heralded the imminent end of the country’s energy crisis.

Here, finally, was an unlimited source of fuel.

Inside this new fuel extraction industry, employment is high — so Oakland writer Tara Marsden tells us in her short story, “At the Gates of the Center.”

By the story’s end, we discover that the corporation eagerly hands off large wads of cash to anyone willing to come through its doors — given they let their brains be hooked up to machines, so the corporation can draw from them a novel source of renewable energy: emotional pain.

This is Marsden’s post-fossil-fuel dystopia, a cautionary tale about a society that’s adapted to its infrastructural needs — at a terrible price.

Like the characters in her story, Marsden has learned what it’s like at the gates of the center — on the outside of the machine, looking in — as well as what it’s like inside.

Before moving to Oakland, she was working full-time for a tech company in San Francisco, but, dragged down by a nine-to-five job, she just wasn’t doing what she wanted with her art.

Now, she lives in West Oakland. She works at E.M. Wolfman, a humble but vibrant bookstore and community space in Downtown Oakland.

She struggles to keep herself afloat financially, just like all her artist friends. She’s had to move five times in as many years.

But art is central to her life again. She’s even outgrown short stories, moving into experiments with poetry and lyrical essays.

And no corporation — fictional or otherwise — is feeding off her emotional energy.

“I realized that, in order to commit to your art,” she says, “that was something that I would have to be willing to do: piece together an income from whatever side hustles I could find.”

It’s Oakland’s lack of respect for that grind that gets her frustrated. For all its talk of affordable housing and the value of artists, the City, Marsden thinks, needs to recognize that reality.

“So many artists do service work on the side,” she says. “You need people who can live here on a service wage.” If artists can’t make a living on that, Marsden says, then they can’t live here.

She depicts another dystopia, one defined by vintage stores and gourmet ice cream. If Oakland’s radical and political artists and writers can’t afford to live here, she says, then “eventually all of Oakland is gonna look like Piedmont or Rockridge, [and] Oakland will just turn into another bland city.”

But Marsden has no faith in the city government helping to fend off such a future.

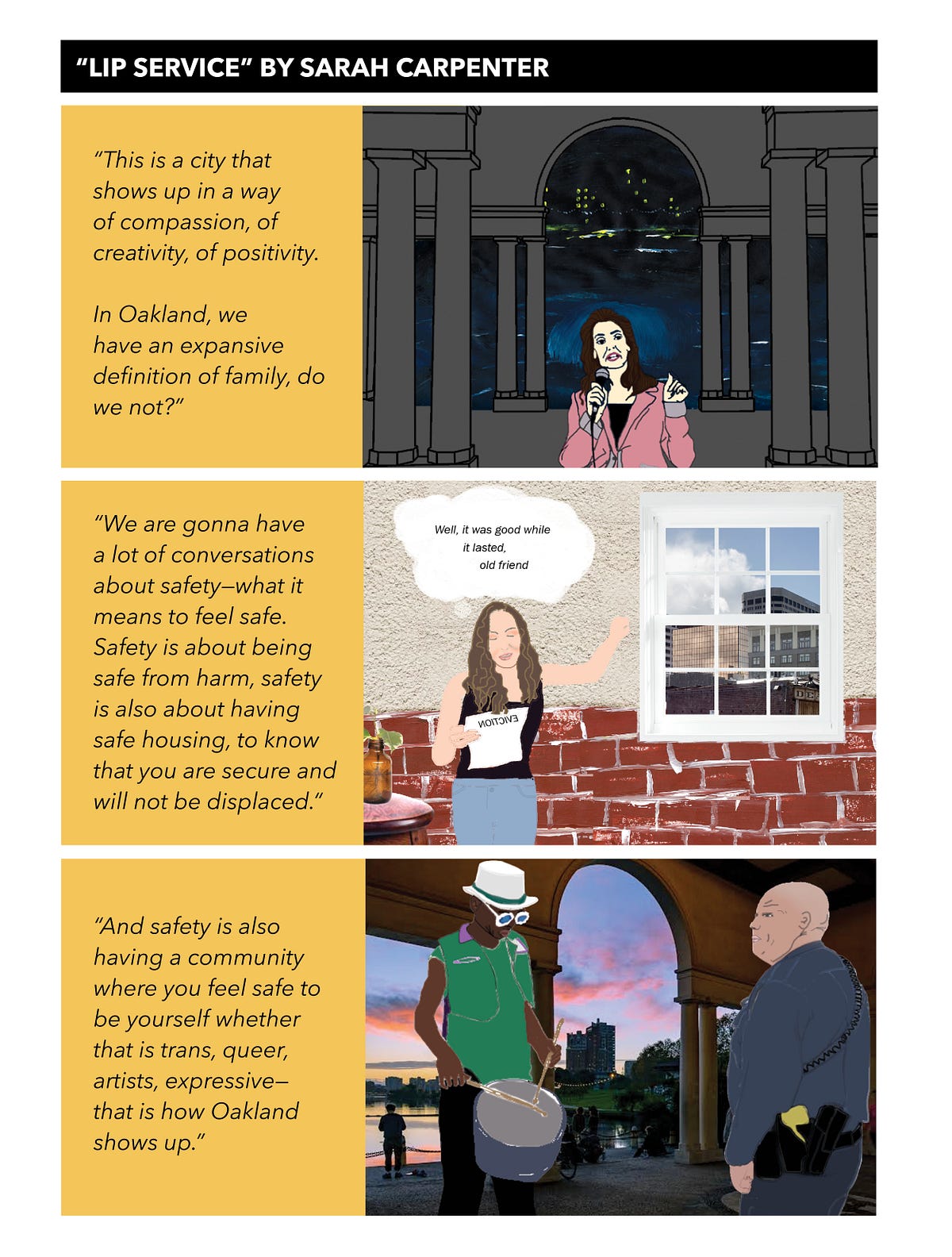

“I hear a lot of talk. I hear a lot of lip service to artists,” she says.

“I don’t know if I believe they’re gonna do anything about it, to be honest, which,” she admits, “sounds really dark.”

DENALDA SIEGRIST WAS THE “FLIRT,” BEN RUNNELS WAS THE “INTROVERT.” Together, they were “Introflirt,” making fun and thoughtful ’80s revival synthpop in Oakland. Their second full-length album dropped in August 2016.

They were rising stars in a city where an uncertain future loomed for independent artists.

Siegrist studied music at Laney College, and sang with the school’s choir and jazz combo. The 29-year-old musician had been working on two pieces for the Laney Music Department’s Fall 2016 choir concert.

On Friday, Dec. 2, 2016, a week before the concert, Siegrist and Runnels went to a warehouse party at a live/work arts space called Ghost Ship.

It was one of many illegal venues that have become more commonplace in Oakland as artists have become priced out of their studios and homes. The building was not permitted to have events like the party Siegrist and Runnels attended, and it failed to keep those inside its walls safe. The duo was among the 36 who perished in the blaze that erupted that night. (See the Tower’s coverage of the Ghost Ship fire here.)

John Reager of the Laney College Music Department says the community didn’t even pretend to hold class the next week, everyone was so grief-stricken.

Students shared stories, listened to some of Siegrist’s songs, and debated whether or not to go ahead with the choir concert.

Ultimately, they decided to perform, and to dedicate Fauré’s “Requiem” in her honor.

“In over 12 years of conducting choir, it was the most heartfelt performance they ever gave,” Reager says.

A bulletin board in the Music Department is unofficially dedicated to Siegrist. Students had turned it into a makeshift altar, occasionally leaving flowers underneath it, or putting up flyers for Ghost Ship benefit shows. Someone even made a silkscreen image of Siegrist on burlap, which Reager now keeps in his office.

“There’s a tremendous spirit to the artistic community in Oakland, and we are very proud at Laney to serve that community,” he says.

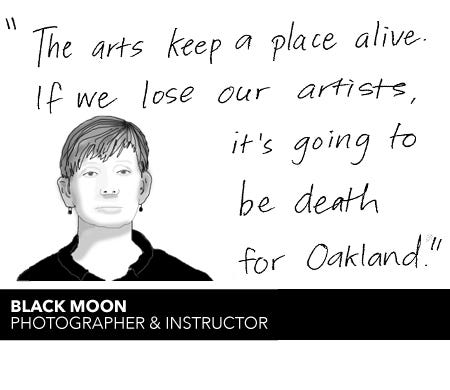

Laney College Adjunct Photography Instructor Black Moon has both served and been a part of that community since she came to Oakland in the early 1970s. She migrated here from Los Angeles to attend what was then called California College of Arts and Crafts.

Moon has seen student artists Siegrist’s age scrambling to remain in Oakland. She says that although it’s always been hard to be an artist here, there used to be spaces available. Artists could take over a neglected warehouse and turn it into an art haven, like Ghost Ship. This was how they were able to live, go to school, and survive.

Post-Ghost Ship, this is becoming less feasible.

“It costs money to make art. It’s not free, and what does one do?” Moon says.

Laney is part of the East Bay’s Peralta Community Colleges District (PCCD), which has among the highest rate of low-income students of all two-year public and not-for-profit colleges in the nation. About 25 percent of PCCD students are in the lowest income bracket, according to New York Times data about college mobility.

And almost 90 percent of the district’s students are adults at least 20 years old.

Hollie Hardy tries to foster these students’ creativity every day, both in her role as an English teacher at another PCCD school, Berkeley City College, and in her role in the literary community.

In her spare time, Hardy co-founded a literary festival in Oakland called Beast Crawl, working alongside fellow Oakland writer Paul Corman-Roberts. For the last few years, they have had the honor of hosting the crowning event for the Oakland Youth Poet Laureate, a program initiated by the City’s public library system.

Hardy also has many students who have participated in Oakland’s Youth Radio, an award-winning nonprofit media production company. Youth Radio has over 50 financial supporters, and is thus able to offer free classes and paid gigs to Oaklanders ages 14 to 24.

“Its great how much support there is for youth arts programs in Oakland,” Roberts says, but he would love to see those models transfer to “artists who find their voices later in life.”

Last year, 19-year-old Akande X graduated from Oakland School for the Arts, a public charter school for visual and performing arts that occupies the historic Fox Theater in Downtown Oakland. It has a lengthy list of community partners and financial supporters, and offers high schoolers a unique education in the arts, for which Akande is thankful.

Akande has benefitted from one example of the City’s investment in art, but he found his true creative home in a little Oakland nook that might soon disappear.

After school on Fridays, he would come into E.M. Wolfman General Interest Small Bookstore in Downtown Oakland.

The books he purchased there had an impact on him. He kept coming in to sit with the bookstore’s owner and talk about them.

Akande found E.M. Wolfman just months after its opening, and is now employed as a bookseller there.

He thinks of the bookstore as a cultural hub, a place where he has made many connections with other artists. “I don’t know where I’d be without E.M. Wolfman,” he says.

Across the squeaky wooden floors there is a handmade display with zines and chapbooks from local writers — the types of books that normally aren’t carried in commercial bookstores. E.M. Wolfman even doubles as a publisher and event space to further boost local writers’ work. It also hosts a film series called “The Black Aesthetic,” and publishes an anthology featuring responses to the films that have been screened.

“The goal,” Justin Carder, E.M. Wolfman’s owner, says, “was to open up a community space… The idea of a bookstore came kind of second.” Carder’s mindset is typical of Oakland’s creative community: he’ll stay as long as he can.

Still, he is optimistic. “We may lose our shop, but all that work around the community that has been built can continue,” he says. “I try not to be too attached to the space.”

But the idea that E.M. Wolfman might not be able to survive Oakland’s rising rent prices, Akande says, is a scary thought.

It’s early evening on the first Friday of May 2017, and Broadway between Grand Ave. and 27th St. is already packed. By midnight, thousands of people from around the Bay will cover the streets of Oakland.

By tomorrow, they’ll be gone, leaving the city to clean up after them.

Before the night ends, Krystal Nzoiwu and Sydney Khan are trying to sell as much of their art as they can to another bustling First Fridays crowd.

Nzoiwu’s hyper-colored paintings lean against the table, depicting playful lighting and fantastic characters. Khan’s eclectic jewelry is on another table, propped up with wooden displays. Over the years, the pair has seen First Fridays change from a grassroots gathering of creators to a heavily organized and competitive marketplace.

Khan says when First Fridays began, vendors didn’t even have to pay for a booth. Artists would find a spot to set up along Broadway, and a community marketplace was born.

Now that First Fridays has been formally institutionalized, such impromptu setups are impossible. Khan says the organizers check your name, and that it’s so competitive, she almost didn’t get her spot this year.

The people First Fridays attract have changed, too.

“It used to be really close,” Nzoiwu says. “People would be bumping into each other and it’d be more interactive, and now it just seems like — ”

“ — more distant,” Khan says.

Both makers lament the loss of a more involved community intent on mutual support. Nzoiwu says First Fridays draws more spectators than participants. Khan says she’s frustrated with the number of vendors who don’t have handmade goods.

Nzoiwu agrees. She recalls her favorite vendors from the early years of First Fridays: two old ladies who sold stuffed animals that they had ripped apart and sewn back together in new funky ways.

“Oakland used to be more funky,” Khan says.

She has even felt the need to change the way she makes jewelry. She prefers to make jewelry that reflects her style: weird and fresh. But lately her bestsellers are the pieces she finds simple and boring.

That’s not the only creative constraint artists face in Oakland. Artists have few choices in the city’s economic climate: sacrifice quality housing, sacrifice artistic integrity, or leave.

Penner and Adley of Zebra Operation have had to make do with small, unorthodox living spaces. One of E.M. Wolfman’s employees, Oakland writer Tara Marsden, quit her lucrative tech job to work at the small bookstore and focus on her writing. In return for these sacrifices, they get something every artist needs: freedom.

Art requires time to practice, think, and be inspired — in addition to the time it actually takes to create something.

Organizations that offer that kind of support without constraining an artist’s vision are in short supply.

ProArts, an Oakland nonprofit, has supported contemporary art since 1974. Natalia Mount, the executive director, says it’s important to support artists by providing the freedom to experiment and make non-commercial works.

Mount says ProArts supported over 200 artists last year alone. She acknowledges that the impact of the increasing rental market and disappearance of underground spaces have contributed to this number. “We’re trying to accommodate a lot more artists than we actually can,” she says, “because there aren’t many spaces.”

Art is central to Oakland’s identity, yet every day more artists are considering that third option: leave.

“The arts keep a place alive,” Laney College’s Black Moon says. “If we lose our artists, it’s going to be death for Oakland.”

The arts have an undeniable impact on the locations that allow them to thrive. Oakland’s entire image has been rebranded in recent years.

In 2013, for example, Oakland was ranked #7 on ArtPlace’s top 12 list for artistic cities in the country. ArtPlace noted that the city was experiencing an energy unlike any it had seen since the 1940s.

But when Bay Area media giant SFGate reported the ranking, the headline read: “Oakland on top 12 list for art, not crime.” The report didn’t include any information about crime in Oakland, but the headline was a telling reminder of the city’s reputation.

Mount thinks more should be done to keep artists in Oakland. “It’s an investment in the city of Oakland,” she says. ProArts hosts free events, and attracts 10,000 visitors a year.

“They don’t pay to get into our events,” she says. “However, they do come to Oakland, so by default they go to bars, restaurants and so forth.”

Businesses benefit from the arts, the City benefits from the attraction art provides, residents benefit from the culture, and of course, artists benefit from practicing their art.

In other words, no one is going to benefit from the lack of arts in Oakland.

PAUL CORMAN-ROBERTS AND HOLLIE HARDY used to look around Oakland wondering, ‘Why aren’t people here?’ The two writers were part of a literary community in the Bay, but most of the events they went to were in San Francisco.

In 2012, they decided it was time for Oakland to get its own literary scene.

“I was struck by the amount of people who said no, you can’t do that in Oakland,” Corman-Roberts says. “And I thought well that’s funny, because most of the writers live on this side of the Bay.”

Partnering with uptown Oakland small businesses, Beast Crawl was founded. It is now a well-attended annual literary festival, entirely volunteer-run, which hosts dozens of readings by local authors in a single night.

Together with a few other writers, Hardy and Corman-Roberts grew their Beast, and last year consisted of 40 readings, with 2,500 people attending.

New to the team is Laura Zink. She is grateful for the community that has surrounded the Beast. “Community works, you know,” she says, “if you put the energy into developing one.”

To Zink, a major benefit of Beast Crawl is that it’s available to anybody, regardless of funds. “Money’s an issue in the Bay Area and it’s a kind of rare thing to have so much art and so much creativity happening in one space where you can actually do all of it for free,” she says. “I think that’s a beautiful thing.”

Beast Crawl is made possible by an independent team of writers who were able to organize with local businesses in a mutually beneficial way. The businesses they occupy get attention, and Beast Crawl gets to use those venues free of charge. By doing this, they don’t have to work with the City, which Corman-Roberts says is costly and time-consuming. They do, however, think about becoming a nonprofit someday in order to become eligible for support should they end up needing it.

Working above ground, or working with government is often seen as an unnecessary roadblock for artists to realize their dreams. Then again, not every form of artist can convince a for-profit venue to let them use their space free of charge. Readings require minimal equipment, which the Beast Crawl organizers help to provide if a venue cannot.

Musicians are used to letting the venue take a cut of their profits, or sometimes all of it if they haven’t brought enough of a crowd in. But, Oakland demonstrates its resilience as buskers take to the BART stations, other musicians host free shows in their own backyards, and drummers gather at Lake Merritt for another summer Sunday.

“It’s up to a stubborn and annoying and persistent arts and activist community to, for lack of a better word, make it uncomfortable for people who aren’t going to be conscious about the kind of world that we want to create,” says Corman-Roberts, from Beast Crawl.

Justin Carder moved to Oakland almost 10 years ago, when Art Murmur was still new, and he remembers people already having discussions about gentrification in Oakland.

He opened E.M. Wolfman in April 2014, on 13th Street in the heart of downtown Oakland. He built the bookstore by hand with the help of some supportive friends.

In the last three years, he has had a front row seat to a changing downtown. He has seen the many nonprofits that used to occupy downtown space become displaced. He says it’s terrible for organizations offering social services to have to move to areas that aren’t as accessible.

Just like Hollie Hardy, Carder is holding his breath. He doesn’t know how long he will be able to keep the bookstore open. “I’m at the total mercy of my landlord,” he says. “As soon as he sees dollar signs, I have nothing to negotiate with. As soon as he decides to raise my rent, the project is over…

“That’s capitalism, man.”

That’s the view geographer Neil Smith takes in his landmark theory of gentrification, first published in 1977, but regaining ground as a new wave of gentrification sweeps the nation.

Gentrification’s defenders, Smith says, make it seem like a consumer-driven phenomenon: People with financial freedom flock to an organically revitalizing urban area because they want something less stale and more vibrant than the suburbs to which they’ve grown accustomed.

It’s that kind of sunny outlook that led the New York Times to print, in 2015, that Oakland was “enjoying a gentrification boom.” (In the version of the article that exists online, the word “enjoying” is conspicuously absent.)

Smith says that gentrification is instead an inevitable part of unrestrained capitalist markets.

Capitalism, of course, relies on cycles — supply-demand, boom-bust — and Smith depicts gentrification as one of its most reliable ones.

Oakland, it seems, was doomed before it even began.

According to Smith, the cycle begins around the time someone like Oakland’s Julius G. Kellersberger shows up with a vision. City planners and private developers put untouched land to use, which, of course, then immediately begins to depreciate.

Greed drives the cycle forward. Property owners in some areas, desperate to slow that depreciation down, invest heavily in maintenance and upkeep, keeping their property values stable so that their investments might someday yield a profit.

Others aren’t willing to make that investment. They either cut their losses and flee, or else convert the property into rental units. After all, a landlord doesn’t need to keep the value of a rental property high; even an under-maintained building can produce a steady flow of rent checks.

Either way, pouring money into a property can’t fend off depreciation forever. Over time, more property owners have to start renting out their spaces. And the more rental units in a neighborhood, the more poorly maintained those buildings become — to maximize profits despite a declining property value.

Before long, outside developers stop coming in altogether, and investment — public and private — vanishes.

Neighborhoods that avoid going full-rental find the same fate, Smith says. Racist housing practices guarantee it.

Throughout the 20th century, he explains, financial institutions were guilty of blatant, discriminatory redlining. The practice meant equating bad neighborhoods with non-white neighborhoods.

For example, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, established in 1933 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, used markers like the type of building, or its age, to determine the quality of a potential investment. Given just as much weight in their assessments was the “threat of infiltration of foreign-born, negro, or lower grade population.”

As Smith tells it, the only people to which banks and lenders would offer low interest-rate loans or low down-payments to get them started were potential property owners in the suburbs — which, then as now, more or less means white people.

Everyone else was left holding rapidly depreciating properties they’d soon become unable to afford to maintain, or even live in.

Oakland already lived through this harsh chain of events through the 1950s and ’60s. Now they’re reliving it.

In 2013, researchers from Berkeley’s Greenlining Institute and Oakland’s Urban Strategies Council together concluded that “the nation’s recovery is redlining African American and Hispanic families across California.”

That year, those demographics made up over half of Oakland’s population. But they received just 10 percent of the money housing lenders had to offer Oaklanders.

Blockbusting, another racist housing practice, only makes things worse. Smith explains how real estate agents used declining property values in white neighborhoods to take advantage of white panic over “ethnic changes.” The more non-white families in a neighborhood, the better the return — they could buy cheap from white families eager to leave, and sell as high they could to non-white families simply looking to move into more well-maintained neighborhoods.

Whites take flight, and again, investment vanishes.

Either way, whether a neighborhood devolves into rundown rentals or foreclosed properties, the result is the same: total abandonment. Landlords can’t sell, nor can they collect enough rent to cover the cost of property taxes or utilities.

Buildings become empty shells.

The phenomenon could be seen in the decades after the 20th-century decimation of West Oakland; it could be seen in 1990s Downtown by people like Paul Corman-Roberts and the San Francisco transplants of the era.

It’s what today’s developers are seeing right now.

“Much abandoned housing is structurally sound and this seems paradoxical,” Smith writes. “But then buildings are abandoned not because they are unuseable, but because they cannot be used profitably.” (Smith’s emphasis.)

Smith says this abandonment can be triggered by a sudden strict enforcement of building codes — something not unfamiliar to modern-day Oaklanders in a post-Ghost Ship landscape.

He also notes, in a brief aside, that this might be when a neighborhood begins to burn.

“There is a certain incentive for landlords to destroy their own property through arson,” he writes, “and collect the substantial insurance payment.”

(See the Tower’s coverage of two separate building fires in Oakland here and here. At press time, federal agencies had officially classified the two fires, and two other similar fires in the area, as arson. No one has yet been charged.)

This neighborhood abandonment marks the peak of what Smith calls the “rent gap.”

It’s the difference between what a property is worth as-is, and what it would be worth if it were wiped clean, a blank canvas on which a developer can paint their own vision of profit.

When that rent gap is high enough, Smith says, gentrification begins, kick-started not by individuals wanting a taste of some authentic culture in a revitalizing town, but by some kind of collective social action.

On first glance, this might sound like an organic swell of entrepreneurial artistry, but Smith would consider this a blip compared to the real culprit.

After all, Smith says, anyone with big plans in a given neighborhood is still at the mercy of the public and private institutions that will decide whether their ideas are worth the investment.

Smith says it’s that collusion between financial institutions, city governments, and professional developers that serves as the initiatory collective social action.

Together, these social actors ensure that lots are razed, buildings demolished, homes torn down, and the ground cleared for the recycling of a neighborhood to begin.

It’s what’s Laney College’s Black Moon fears she’ll see. It’s what Beast Crawl’s Hollie Hardy knows she’ll see. It’s what tens of thousands of Oaklanders who have been pushed out to Richmond, Hayward, and other East Bay cities in recent years have seen — and, if Smith is correct, will see happen in their new homes someday soon.

And once the ground is clear, city planners and private developers can put the untouched land to use, which, of course, then immediately begins to depreciate.

Greed drives the cycle forward…

You know the rest.

The key to stopping gentrification, then, is taking a long, hard look at the relatively unrestrained land and housing markets Smith ultimately blames, markets made possible by capitalism. The key, as well, is reconsidering whether such an economic system is as natural or permanent as we think.

“It wasn’t until the protests began that some of us started paying attention,” writes Tara Marsden in the middle of her aforementioned dystopic short, “At the Gates of the Center.”

The “ragged, thin hippies and liberal housewives fueled by righteous fury” march in front of the corporation at the dark heart of the story; they carry signs with all-caps slogans:

PEOPLE AREN’T BATTERIES.

PAIN IS NOT POWER.

“Nearby stood an angry, bedraggled young woman,” Marsden writes. “They’ve found another way to bleed us dry, she said.”

Unpleasant fiction reflects unpleasant realities, and Oakland artists have plenty of dark threads with which to weave their works. But they also have a “righteous fury” to unleash, using it to push the city towards a novel future, rather than a repetition of the past.

“I do believe strongly in the people being able to do something about it,” Marsden says, echoing the themes in her story. “I put a lot of faith in the people who are resisting and not in the people who have the power.”

Eric Arnold is proof: during the early days of the Oakland Creative Neighborhood Coalition, he and his co-founders held a rally around the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan protesting the lacking, non-inclusive nature of its community engagement arm.

Their protests, according to Arnold, pushed the team to revise the plan through an equity lens — which ultimately resulted in Arnold being brought on-board, to work on community outreach.

“We complained we were outside, and now I’m a part of the process,” he says.

Arnold is advocating for inclusive cultural zoning around Oakland’s art districts, with the City promoting these districts as destinations that could create more economic opportunities.

After all, he says, “we don’t just need affordable housing.” He believes that, without economic development, people might be able to pay for housing — but not much else.

That development “is gonna take policy work,” he says. “The only thing that prevents these policies from being passed is political will.”

And if that political will isn’t there, he continues, “we need to be willing to vote people out of office.”

He urges Oaklanders to take a look at the leadership: after all, history shows that the plans they execute, whether they succeed or fail, or whether they exist at all, can have decades-long reverberations into the future.

Otherwise, it seems this time-tested cycle — economic crash, grassroots revitalization, forced displacement, and inaccessible redevelopment — might continue endlessly, built on the backs of the artists who came before.

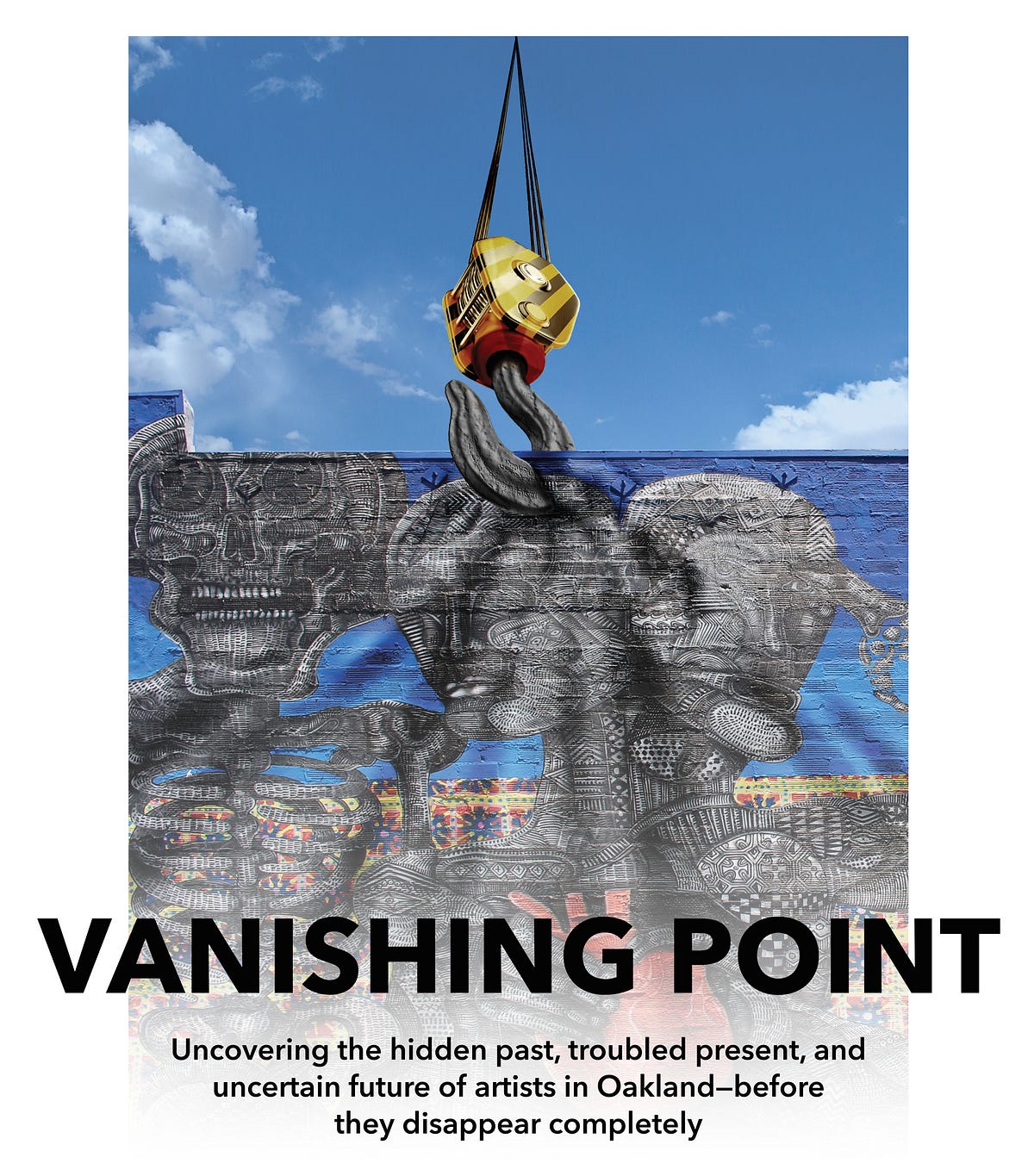

Sarah Carpenter’s photo illustration at top represents the threat developers pose to art in Oakland. The mural depicted was painted by Zio Ziegler at 1628 Webster Street.

Special thanks to Laney College Journalism Professors Burt Dragin and Scott Strain, journalists Sarah Burke, Sam Lefebvre, and Peter Moskowitz, and the Oakland arts community for their support in writing this story.

Sarah Carpenter is the Editor-in-Chief of the Laney Tower. Brian Howey is the News Editor, and KR Nava is the Design Editor. E-mail us at thelaneytower(at)gmail.com.

The version of the story that appeared in print incorrectly stated that California’s Proposition 13 passed in 1983. It passed in 1978.

It also incorrectly stated that Green Day, Metallica, and Faith No More were Oakland-born bands. Green Day founders Billie Joe Armstrong and Mike Dirnt were born in Oakland, but the band was founded in nearby Pinole, Calif. Metallica was founded in Los Angeles, but recorded their first album while based in the East Bay. Faith No More was founded in San Francisco.

The article has been changed accordingly.

**UPDATE: The bill to repeal the Costa-Hawkins Act was called AB1506. It had its first and final public hearing on January 11, 2018, where it only received three of the four votes needed to move forward. Bay Area Assemblymembers David Chiu (SF), Rob Bonta (Alameda) and Mark Stone (Santa Cruz) voted for AB1506.