16-year-old Lucy Siale organizes Oakland rally to defend immigrant rights

By Sarah Carpenter

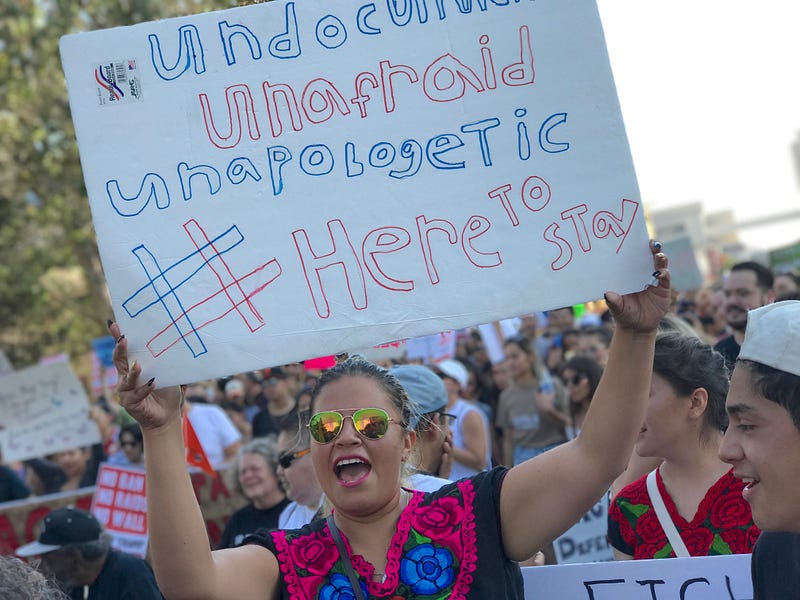

A young woman in overalls stood up in the back of a pickup truck parked at Broadway and 14th Street in Oakland on Sept. 9. The crowd she had invited to Oscar Grant Plaza gathered around as she chanted into a microphone, “No bans! No walls! A sanctuary for all!”

Then, she introduced herself: “My name is Lucy Siale. I am a 16-year-old high school student. I’m a first-generation American student. Both of my parents are immigrants; they have green cards. My father came here in the ’60s. We are here to defend immigrants. We are here to defend undocumented immigrants. We are here to defend all of the DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] recipients. And we are here to defend every single dreamer, am I right?”

Hundreds of people roared in agreement. The front rows were reserved for those with disabilities; sign language interpreters were paired with each speaker; and Siale demanded that the march to follow be at the pace of disabled participants.

“If you are not organizing events that are accessible to ALL folks, you’re not being radical,” she said.

As the ralliers marched down Broadway toward the Oakland Police Department, the crowd grew into the thousands.

One of the speakers, Marlene Gutierrez, a former Merritt College student, is a DACA recipient. She said she works for Girls, Inc., whose tagline is “Inspiring all girls to be strong, smart, and bold.” She then asked America if it thought she had nothing to offer.

Michael Mendoza, from Socialist Alternative, expressed confidence that America would not allow DACA to be taken away for good. His take was that “we need to address the system that is producing people like Trump.” He said he feels “motivated and inspired to know that we’re going to come together and we’re not going to let this happen.”

Just after the decision to phase out DACA was announced on Sept. 5, emergency rallies were held in cities across the United States.

Activist group By Any Means Necessary (BAMN) organized rallies in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Berkeley — all at 5 p.m. on Sept. 5.

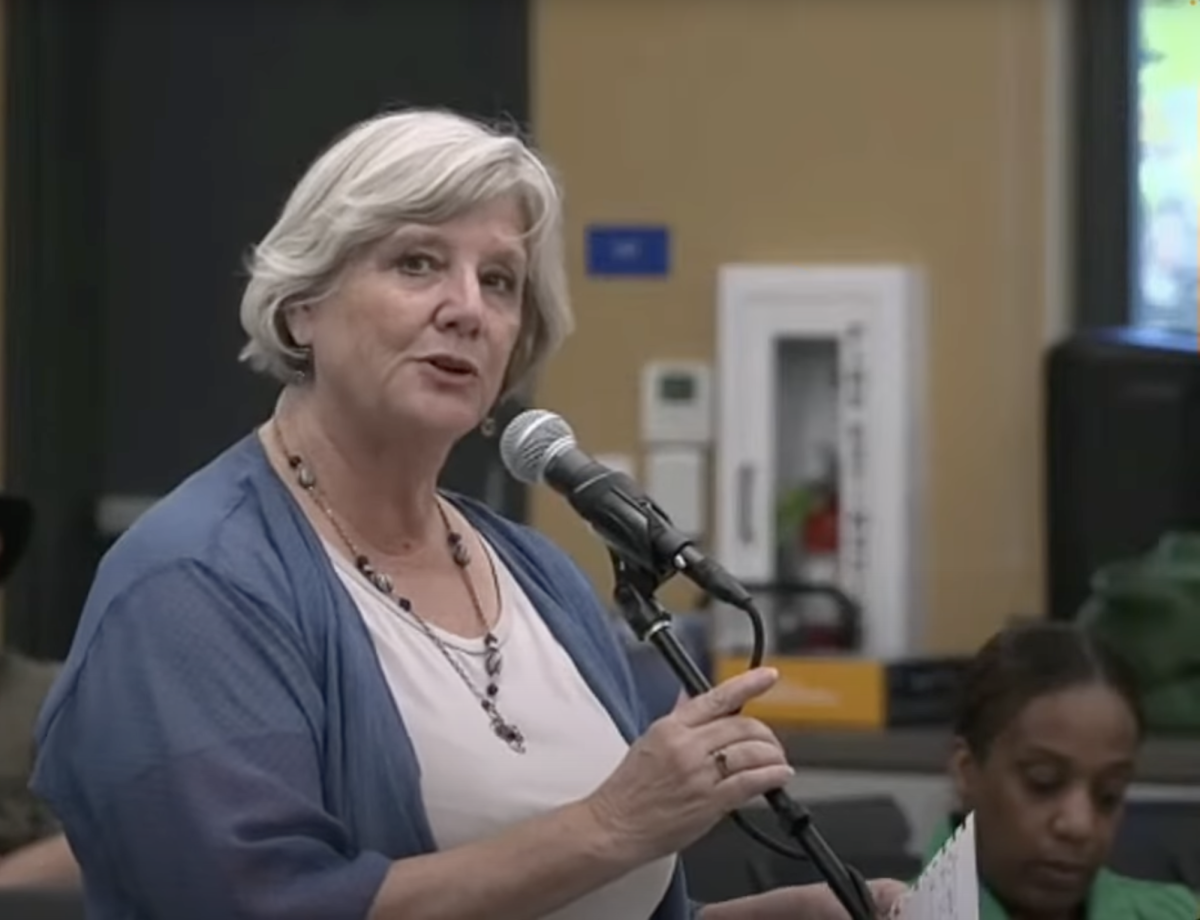

Yvette Felarca organized the protest in Berkeley, which took place in Sproul Plaza at her alma mater, UC Berkeley. Felarca teaches English, history and English as a second language at a Berkeley middle school.

She is adamant that those who support Trump’s decision to end DACA are in the minority. “A vast majority of Americans support the Dreamers. There is even a majority of Republican support for the Dreamers!” she said.

The immediacy of the emergency rally brought gut reactions from those who feared deportation. A young woman stepped up to the mic, shy and nervous. “Just five seconds ago, I was just another face in the crowd,” she said. “I just wanted to show you: this is the face of a DACA Dreamer.”

She shared her fears with those who gathered, reminding American citizens that they are lucky. “All I want to do is do well in my classes. This is the last thing I want to have on my mind. I don’t want to feel like another statistic,” she said. “I don’t want to feel like I could be taken away from a country that I call home.”

A history of DACA and DREAMers

By Dejon Gill

The first version of the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act was first introduced to the United States Congress in 2001. This piece of legislation is the origin of the name “DREAMers” for people who were brought illegally to the U.S. as children. Since 2001, the DREAM Act has been reintroduced in Congress in several forms, and it has always had bipartisan support. It was nearly passed in 2010 when it passed in the House of Representatives, but fell five votes short in the Senate.

“The overall idea was that there would be specific guidelines that DREAMers would have to meet, and if they did, they would have a path towards citizenship,” according to Felipe Wilson, Political Science Instructor at Laney. As well as a path to citizenship, versions of the bill also provided for conditional permanent resident status, which would allow for DREAMers to attend institutions of higher education and work legally. The conditions include things such as age of arrival and a lack of felony convictions.

Due to a lack of progress in getting the DREAM act passed, then President Obama signed the executive order known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in 2012. “DACA is a protection from deportation for certain individuals based on age and work/school status for two years which can be renewed,” Wilson said.

DACA does not provide a path to citizenship, but it does allow recipients to have a Social Security number so that they can work and drive legally, pay taxes, attend college, and serve in the military.

DACA recipients are required to have arrived in the U.S. before their 16th birthday, have not been convicted of a felony or serious misdemeanor, be born on or after June 16, 1981, and meet other conditions. After paying the initial fee and submitting the application, DACA recipients are required to re-apply every two years and pay an additional $495 fee.

DACA critics claimed that it was an “over-reach on the part of the President and an attempt for him to make laws by bypassing Congress,” Wilson said. Supporters point out that it was meant to be a temporary solution meant to protect people who are generally seen as a very low priority for immigration enforcement.