Laney student seeks future as educator amid unwelcoming present

By Brian Howey

The termination of the DACA program has led to confusion, anger, passion, and strength from the thousands it has affected.

We at the Tower feel it’s important to put a face on the statistics, to present the stories of people who have come to this country under varied and often harrowing circumstances.

The following is an account of Laney College student Sasha Shane’s life. Her story is just one from the diverse group of DACA recipients, or “Dreamers” attending Laney and living in our communities.

The termination of the DACA program has led to confusion, anger, passion, and strength from the thousands it has affected.

—

Sasha Shane remembers the heat of the Sonoran desert as she walked through the day. At night, she remembers her mother turning her regularly next to a fire to keep her from freezing to death.

Shane and her mother walked for three days through the desert from Mexico into Arizona in 2002.

As they entered the United States, they passed white crosses commemorating those who had died attempting what mother and daughter were about to try. “It wasn’t until then that me and my mom realized how dangerous that actually was,” she said.

A child’s thermos full of water — about a half gallon — was all 11-year-old Shane had for the walk. She tried not to drink from it unless she absolutely had to.

She and her mother crossed the border with a small group led by a coyote — a people smuggler. On the third day, the group came to a stretch of desert that was wide open.

A child’s thermos full of water — about a half gallon — was all 11-year-old Shane had for the walk.

—

That was on Shane’s 12th birthday. But they didn’t celebrate. Shane and her mother had lost track of the date, and it would be several days before they remembered Shane’s cumpleaños.

After their run across the desert, they were picked up in a strange car and driven to Phoenix, where they stayed two days in a cramped and sweaty apartment with 30 other immigrants.

Another coyote them up in a van and drove them to Oakland. Shane lay on the floor at the feet of her fellow immigrants, wrapped in a carpet.

Below everyone’s feet, Shane felt a mixture of fear, excitement, and resentment for her mother.

—

She remembered her mother’s earrings that day: the beautiful gold flowers she wore with her best outfit, to distract prying eyes from the immigrants in the backseat.

Below everyone’s feet, Shane felt a mixture of fear, excitement, and resentment for her mother. She had given Shane less than a day’s notice before they left their home in the southern state of Guerrero, Mexico.

Shane couldn’t say goodbye to her school friends. To them, she was there one day and gone the next.

Shane’s mother, a politically outspoken teacher, began to think they would be safer in the U.S. A break-in left their house in Guerrero gutted of possessions, and cemented her mother’s decision.

Once in Oakland, Shane and her mother reunited with her father and brother, who had left Mexico the year before.

Shane’s first experiences of Oakland were homelessness and confusion. Her parents struggled to find a home for the family. She was sent to live with a cousin while her parents searched for an apartment.

The family spent the next decade finding a place in their adopted home, learning the language and culture through trial and error.

The age of ‘Dreamers’

It was June, 2012. A 22-year-old Shane wondered if the new Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, implemented in Aug. of that year, would fall short of its promises.

“I thought it wasn’t enough,” she said. “I thought, ‘People are going to get comfortable, and this isn’t going to work.’”

Shane was one of many undocumented immigrants at the time who suspected DACA policy was a trick to convince immigrants to share names and addresses that would later be used to track down and deport applicants to the program.

But over time, she began to feel she had nothing to lose.

Shane — now a Laney student — lacked the proper working visas and was forced to work wherever she could, which she said led to mindless, dead-end jobs.

The constant stress from being at risk of deportation began to wear her down. “That was messing with my emotional and physical health,” she said.

Soon DACA was Shane’s only chance at residency and a new life. So she signed up.

Shane remembers how she felt when she received the notification that she had been approved for the DACA program while sitting in her computer class. “I just started crying,” she said. “I couldn’t believe that I was actually going to get my work permit.”

Nearly 790,000 people are protected from deportation by the DACA program, according to data from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Of those protected, nearly 223,000 live in California.

One of Shane’s brothers and 35 of her cousins are DACA recipients. Her brother and four of those cousins attend Laney College.

But Shane still feels that it isn’t enough. Without a route to citizenship, Dreamers were stuck in a legal grey area.

On Sept. 5, 2017, President Donald Trump announced the termination of the DACA program, cutting short the dream so many had come to believe.

But Shane still feels that it isn’t enough. Without a route to citizenship, Dreamers were stuck in a legal grey area.

—

Congress has since been scrambling to create and pass alternative legislation to protect DACA recipients.

Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) claimed on Sept. 13 to have worked out an unofficial deal with Trump cementing DACA protections into law.

But Trump responded to Schumer and Pelosi’s claim by Tweet the next day, writing, “No deal was made on DACA.”

Fuerte con DACA o no

With or without DACA, little has changed for most illegal immigrants, Shane said.

Shane pointed to the Obama administration’s record number of deportations as evidence that the U.S. hasn’t changed it’s attitude toward immigrants, it was just quieter about it for eight years.

Regardless of who’s president, Shane and her family have to take care of themselves.

But that’s not to say they don’t have any support.

The day after DACA was terminated, the Peralta Community College School District (PCCD) sent emails to the student body, assuring them that the district would not “act on behalf of federal agencies to enforce immigration laws or aid in deportation.”

PCCD’s response to DACA was far better than some schools that remained silent on the subject, Shane said, but there’s room for improvement.

She said Peralta’s staff could use better training on the ins and outs of DACA and how to be sensitive to the needs of DACA students.

“Starting the conversation is the beginning,” she said.

Shane married a U.S. citizen in 2012, and was granted residency in 2016. The termination of DACA no longer affects her status in the U.S.

But many of Shane’s cousins are under the threat of deportation if congress can’t nail down legislation to protect them.

Even in a political climate defined by a president who has called Mexican immigrants criminals and “rapists,” Shane says her parents still carry the same label: illegal.

In Mexico, Shane’s father was a doctor and her mother was an elementary school teacher. Now her father works as a groundskeeper at a local golf club and her mother is a housekeeper.

Shane said her mother struggled with what she viewed as a step down, professionally. Her father is more humble, and doesn’t seem to mind his situation as much.

Neither of her parents regret their decision to come here, she said. “I think that they would do it all over again.”

But Shane said her parents feel trapped in the U.S. They can’t leave unless they sneak back into the U.S. when they return, and they want to travel the world.

Shane thinks her parents may retire in Mexico so they can get their Mexican passports and travel without fear of deportation.

Either way, she’s not worried about them. She’s confident they will persevere.

“I’m past fear,” she said.

But her extended family, the cousins who still rely on DACA, face deportation without it. It’s their future Shane worries about.

Strength and Uncertainty

Shane used to have trouble with her identity. When she visited her hometown in Mexico, people couldn’t place her accent and asked her where she was from.

On a recent trip to Brazil, she told people she was from Mexico, but when they asked her to share something about her home country, she couldn’t think of what to say.

Shane used to have trouble with her identity. When she visited her hometown in Mexico, people couldn’t place her accent and asked her where she was from.

—

Back home, she thought about it, and came to a realization.

“I’m from here,” she said.

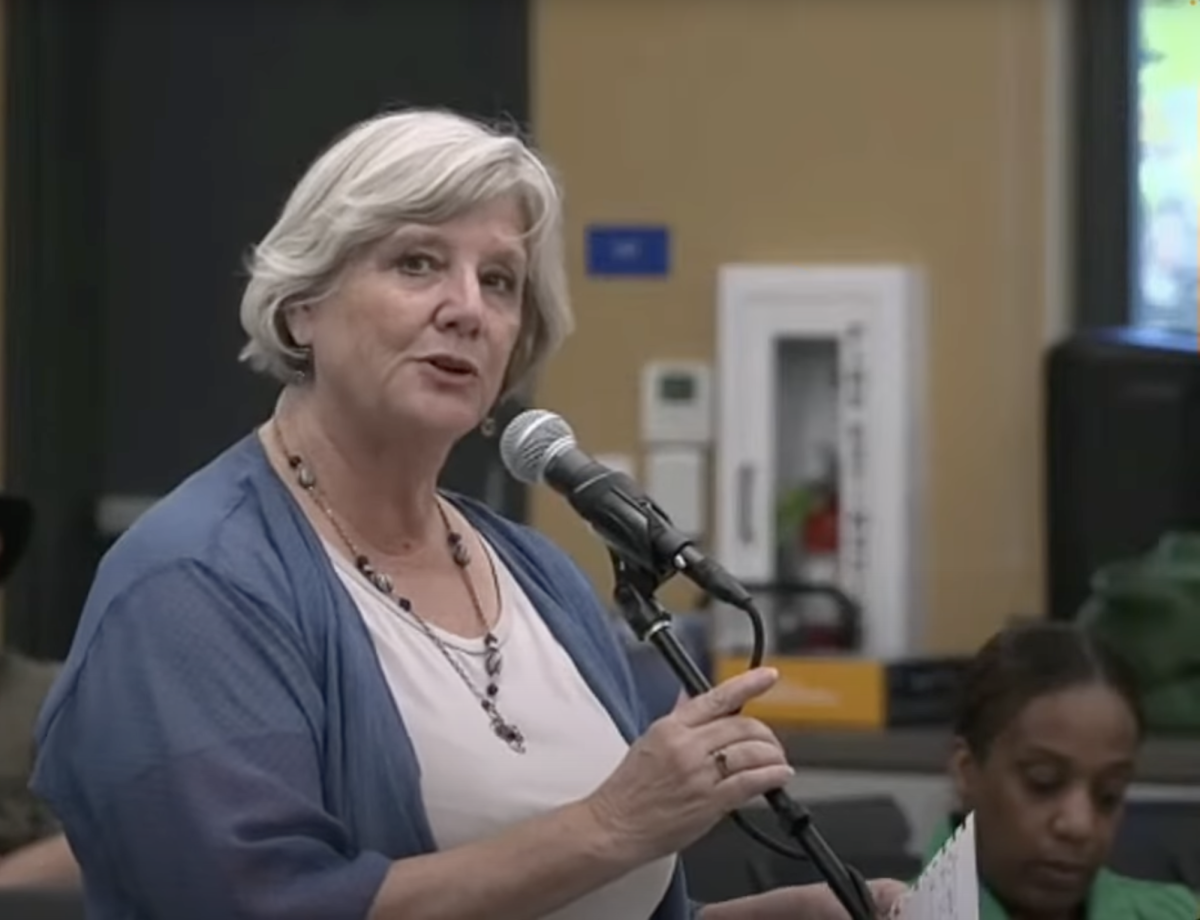

Now Shane is an organizer at the Bay Area Parent Leadership Action Network (PLAN), a group that organizes workshops for parents of K-12 students in low-income areas.

Parents are trained in what the organization calls “Transformative Family Engagement;” a strategy of shared responsibility for students’ success between family, community, and educators.

Someday, Shane will earn a PhD in education, she says. She plans to be the superintendent of the Oakland Unified School District.

Education has always been important in her family, Shane said, and she wants to ensure that the children of Oakland have access to quality education.

She’ll transfer to a local university soon. The name of the university is unimportant, she said. It’s the experience she carries with her — helping kids and fighting for their futures — that matters.

On Sept. 22, Shane says her mother was assaulted as she walked down the street in Oakland. A white woman allegedly approached Shane’s mother, began to berate her, and tried to strike her.

Education has always been important in her family, Shane said, and she wants to ensure that the children of Oakland have access to quality education.

—

Oakland Police were pessimistic about the chances of finding her mother’s assailant, Shane said. The attack has left her mother shaken, but Shane is confident her mother will recover. She’s been through worse.

Dreamers and their parents have endured hellacious border crossings and callous discrimination. They’ve experienced language barriers, homelessness, and depression.

Through it all, they continue to flourish, despite overwhelming challenges. They’ll keep living — with or without DACA, here or in their countries of birth — but that doesn’t mean they don’t need

DACA wasn’t good enough for Dreamers, and neither is their current legal limbo, Shane said. Something has to change, she said.

Dreamers deserve better.

If you or someone close to you is affected by the DACA termination, the Laney Tower would like to tell your story. We are especially interested in students from Asian, African, or South American backgrounds. Anonymous contributions are accepted. Please contact us at [email protected] or call 510 464 3460 for more details.

Brian Howey is the News Editor for the Tower. Email him at deathandtaxes(at)tutamail.com.