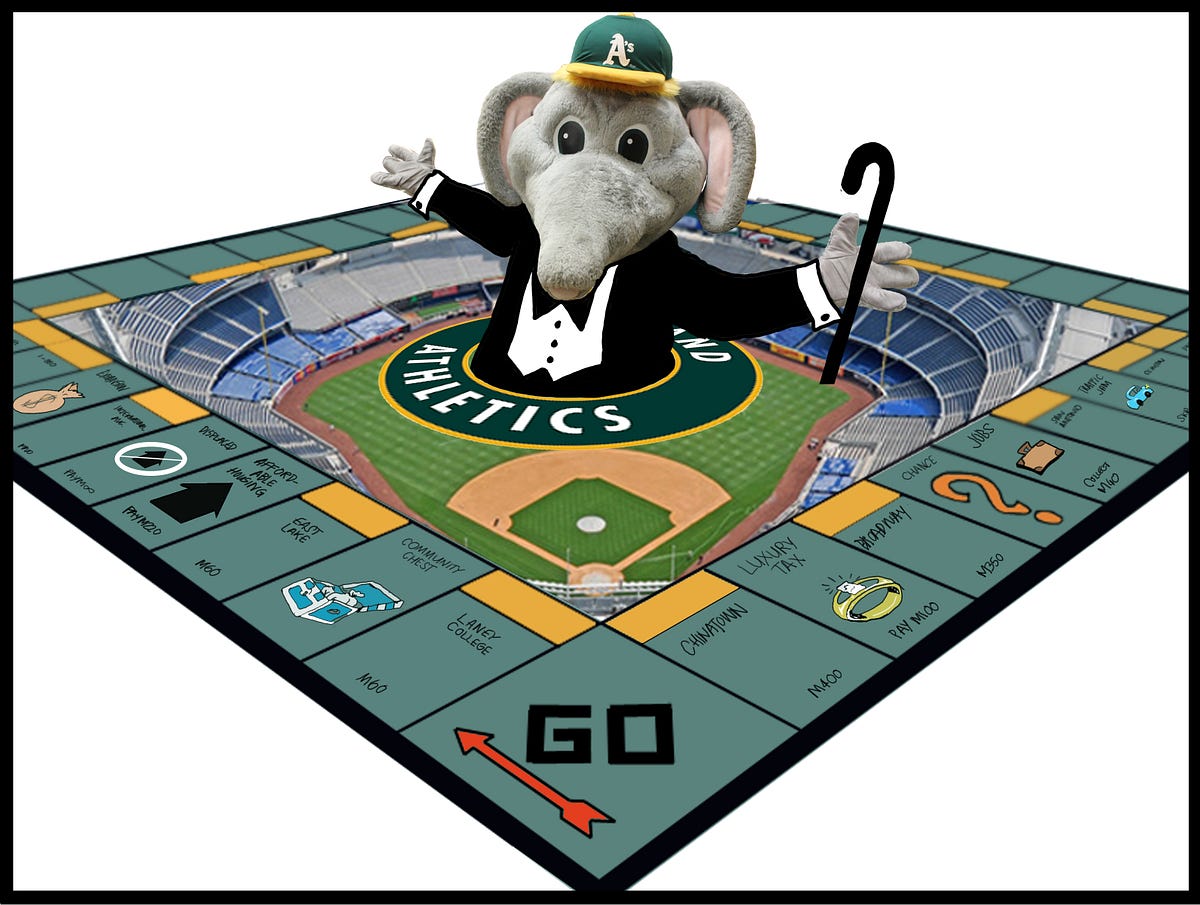

The A’s want in. Who will be out?

The Peralta Board of Trustees will announce Dec. 12 whether they will begin negotiations to lease district land to the Oakland A’s for their new stadium. The decision may have a serious impact on where locals live and how they learn.

By Brian Howey and Sarah Carpenter with additional reporting by Yohana Gebre, John Reimann, Argel Brown, KR Nava, and Kyiakhalid Ruiz

The Oakland A’s announced Sept. 12 their preferred location for a new ballpark: the Peralta site. The response has been a patchwork of dismay and triumph.

The site is spitting distance from Lake Merritt, a BART station, and downtown Oakland and is a dream location for any business venture in a rapidly developing area.

It’s also across the street from Laney College and bordered on all sides by immigrant and working-class communities.

The site is perfectly situated to fit the standards of both the A’s and Major League Baseball (MLB). But would the ballpark meet the standards of its future neighbors?

Some die-hard A’s fans see the new stadium as a fresh start for the team in a convenient location, and an opportunity to contribute to the communities surrounding the site. They say the ballpark will bring customers to nearby businesses, and new development to what they see as a long-stagnant area.

They also believe the new location will make access to games easier for A’s fans all over the Bay Area, a change that could revitalize the franchise and keep the team “rooted” in Oakland.

But many of the community groups anchored in nearby neighborhoods see the stadium as an invader, a catalyst of gentrification, and a whitewashing force of cultural assimilation.

Many say the educational environment of Laney College will be permanently damaged, which could further decrease enrollment and force the school to relocate or close.

They also fear the ballpark will displace poor and working-class families, particularly those in the Chinatown, Eastlake, and San Antonio communities.

On Dec. 12, the Peralta Board of Trustees will decide whether to begin negotiations with the A’s. Regardless of their decision, Laney College, the communities surrounding the Peralta site, and Oakland itself will likely remain divided on the issue.

The stadium could define the city as a haven for progressive development with the needs of the working class and dispossessed at heart. Or, it could paint the city as a playground for hard-nosed developers with little consideration for those they brush aside.

For this special issue, the Tower conducted dozens of interviews, collected poll data, and visited meetings and rallies from both sides of the ballpark fence to provide our readers with a comprehensive look at what a stadium at the Peralta site could mean for Laney, the nearby communities, and Oakland as a whole.

Part One: Laney College

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Laney College sits nestled between Oakland’s crown jewel, Lake Merritt, and the city’s vaunted downtown epicenter. The college was founded in 1953 — known then as Oakland City College — and is now the largest of the four Peralta Community College District (PCCD) schools.

The Laney area is familiar with development proposals and the presence of sports teams. An Oakland A’s “Peralta Site” was first suggested in 1960 at almost the exact location today’s proposed stadium site.

The Oakland Raiders played at Frank Youell Field from 1962–1965 on what is now Laney’s parking lot.

In 1992, Kaiser Permanente attempted to buy Laney’s athletic fields to build their new hospital.

Resistance from Laney faculty and community members killed the Kaiser deal. When local media found that then-Peralta Chancellor Robert J. Scannell had withheld essential information from the Peralta Board of Trustees, he chose to retire early.

Today’s proposal from the A’s is a list of offerings. The team has promised to bolster Laney’s underfunded infrastructure with fiscal contributions to the school.

“Education has always been one of our focus areas,” said Catherine Aker, vice president of communications & community for the A’s.

The A’s host annual scholarship initiatives and job-shadowing programs for local schools. Aker said the team will continue those programs as part of their community engagement, and they could extend similar programs to the PCCD.

“We need to see these [jobs] for what they really are: opportunities for cheap labor.”

— Amado Canham, Laney sociology student

In 2012, the district made plans to build a sprawling, open-faced campus with a new library and a much-needed parking structure. Campus renovations are projected to cost $162 million — 57 percent of the total cost of an entirely new campus, according to a 2016 Laney Facility Index Report. Some think the funds promised by the A’s could be used toward the new campus, or at least to make much-needed repairs.

Louis Quindlen, Laney’s machine technology department chair, said the Board of Trustees has mismanaged Measure B funds, a 2012 voter-approved parcel tax that provides around $8 million to the PCCD.

“They have not done the maintenance work that is needed to be done,” Quindlen said. “The bond money that was supposed to be invested here has not been invested.”

Quindlen is one of several faculty members — from both sides of the stadium argument — who believe this lack of investment is the source of many of Laney College’s infrastructure issues. But unlike most faculty, he believes an outside revenue stream, such as funds from the A’s, could solve Laney’s problems.

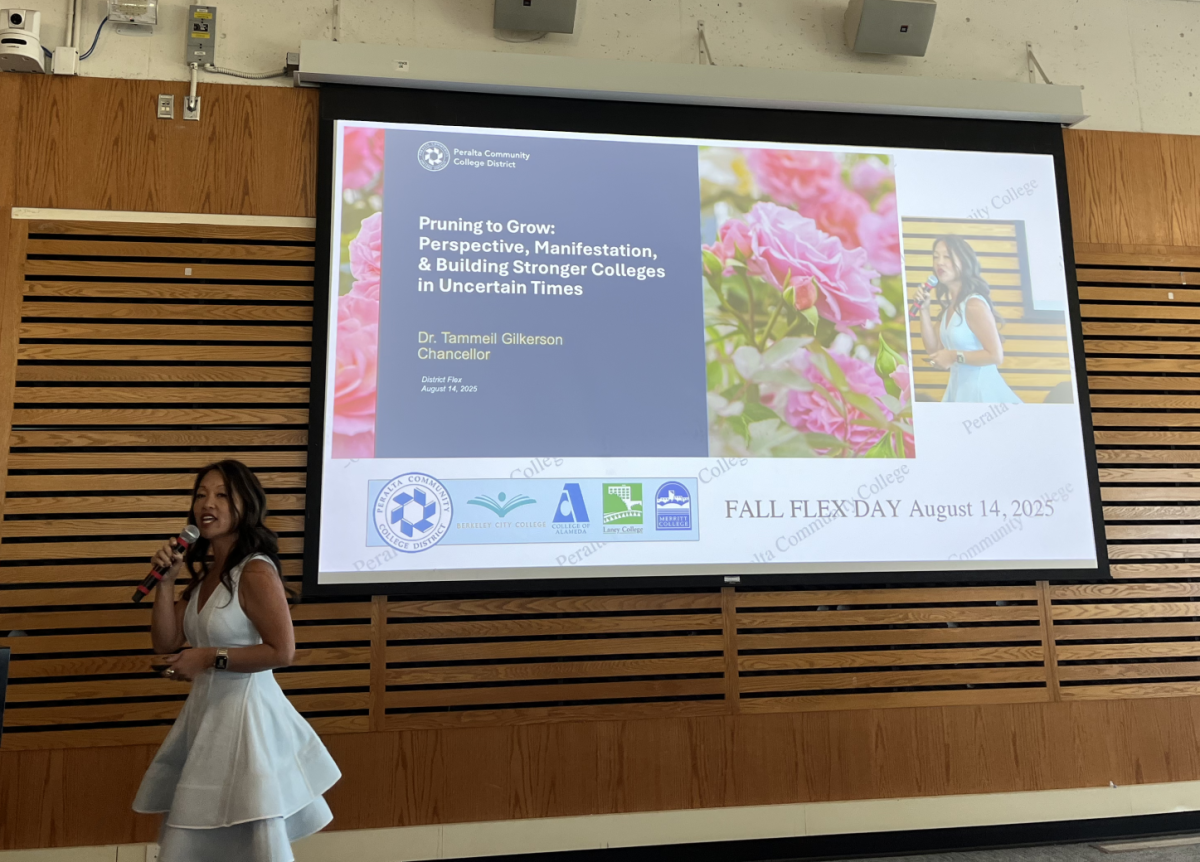

PCCD Chancellor Jowel Laguerre agrees. “We have had challenges with the facilities at Laney,” he said, and added that an agreement with the A’s could provide essential revenue to revitalize Laney and the other Peralta schools’ infrastructure issues.

Laguerre has stressed that the district’s land is not for sale and “no deal has been made.” If the PCCD decides to move forward with negotiations with the A’s, he said the terms include a 99-year lease of the land.

Much of the income from a deal with the team would come from this lease agreement, he said.

Many Laney students are homeless, and Oakland A’s President Dave Kaval has hinted at the possibility of providing student and faculty housing for Laney.

But for students, one of the more lucrative possibilities the A’s have offered Laney is jobs and internships at the new stadium.

Sharon Cornu, a consultant hired by the PCCD Board of Trustees to strategize negotiations between the A’s and the district, said these opportunities are “critically important” for Laney to explore.

“If the master developer is contractually obligated to work with this type of enterprise, the project can deliver long-term employment benefits for students and workers,” she said.

Laguerre shares her optimism.

He said it’s “too soon to tell” whether the stadium would be good or bad for the district, but he thinks internship opportunities for students would be one of the largest gains for the district.

“What I want to see is a strong tie between our programs and what the A’s have to offer,” he said. “To have this big project in the city will be very, very good for our students.”

Laguerre said Laney’s culinary arts, sports, and media programs could gain jobs with the A’s, as well as Merritt College’s Horticulture Department, Berkeley City College’s Multimedia Department, and College of Alameda’s Fashion Design Department.

But Laguerre said it would be at least two years before any negotiations could solidify with the A’s.

Amado Canham’s eyes are steely, his voice staunch and unwavering. The Laney sociology major is friendly, but when he speaks, it’s clear he’s not a fan of the proposed stadium.

Canham is a member of the Laney Land for Students Coalition, one of several community groups who together call themselves the Stay the Right Way Coalition (StAy).

Members of StAy believe the A’s should rebuild their stadium at the Coliseum site.

Canham and StAy say that a new ballpark will clog the Laney area with traffic, overwhelm the school with crowd noise from games, and over-crowd the campus with fans as they walk between Lake Merritt BART station and the stadium.

“It’s going to be real hell,” he said.

And Canham thinks the job and internship opportunities promised by the A’s will be “dead-end” service or retail jobs no different from those already available to students. “We need to see these [jobs] for what they really are: opportunities for cheap labor,” he said.

He’s also concerned for the safety of female students, who may face harassment from drunk fans after games.

“Students need to feel safe,” Canham said, adding that thousands of fans — and the police needed to watch over them — would make many students uncomfortable.

Canham said students of color already face harassment from police in their daily lives, something they come to Laney to avoid.

Laney Psychology Professor Kimberly King is a leading voice of Laney’s faculty who are opposed to the ballpark. She said the negative impact to Laney would far outweigh the opportunities the A’s have offered.

“Our students aren’t going to like [the stadium] and I’m not going to like it either,” King said at a Peralta Federation of Teachers (PFT) meeting in October.

The team hosts around 80 home games per season, in addition to monster truck rallies and concerts.

Like Canham, faculty are concerned that foot traffic between the proposed 35,000-seat stadium and Lake Merritt BART station could trash the campus.

“Eighty-five days a year, you’re gonna have 20,000–25,000 people coming through the campus. They’re gonna use the bathrooms,” said former Laney Athletic Director Stan Peters.

Laney’s bathrooms are notoriously filthy, and Peters said fans who use them would dirty them even more.

The A’s have yet to release any specifics about the location of fan parking, but Kaval has suggested that Laney’s parking lot could be converted to a parking structure shared by fans and students.

Kaval didn’t suggest where students would park while Laney’s new parking facility is built.

For some faculty and students, parking is the least of the school’s worries. They believe the school itself could be displaced by the stadium and resulting developments.

Laney records show a 9.4 percent decline in enrollment since 2014, and both King and Canham said the increased traffic, limited parking, and crowd noise from the stadium would sink enrollment numbers even further, until the college has to close its doors.

Kaval disagrees. “We’re not moving Laney College,” he said.

By supporting Laney’s infrastructure and offering jobs and internships to students, Kaval said the stadium would help the school rather than harm it.

The decision to allow the A’s to build at the Peralta site lies with the Board of Trustees.

—

A’s representatives like Kaval and Aker said the team could provide student housing, soundproofed classrooms, and give fiscal support to Laney as solutions to the list of concerns over the stadium, and he’s repeatedly said that they are willing to address all of the issues the school has.

“This needs to be a win for the A’s, the community, and for the Peralta Colleges,” Kaval said at a November Peralta faculty union meeting.

So, what if the A’s hit a homerun, and fulfill all of their promises? Laney Athletic Director and head Football Coach John Beam doesn’t discount the idea.

“I don’t want to come in and say ‘No, no, no,’” he said in a March interview with the Tower. “What if there’s this great idea where everybody can be happy? Then I want to listen to it.”

Beam and Quindlen are part of a small group of instructors who see the new ballpark as a potential plus for Laney.

Stanford Emeritus Economics Professor Roger Noll doesn’t share Beam or Quindlen’s optimism. He’s spent years studying the effects of professional sports stadiums on cities, and he’s concluded that most stadiums are an all-around loss.

To Noll, the most substantial argument against the new stadium is the consequences for Laney College.

“It’s going to make access difficult for the faculty and the students,” he said. “It’s harmful to the college.”

Noll said Laney would get the short end of the bat if the A’s build next door.

Laguerre said that income from the A’s could be beneficial for the district.

“Some institutions are able to meet their needs because of secondary sources of revenue,” he said. “I’d like to see us as a community come together…to talk about what investment we want to make in Peralta.”

But Kimberly King is among many faculty who are skeptical whether the PCCD would properly spend funds from the team.

They see the district’s financial history as evidence that funds may not be used for Laney’s betterment.

“Money has continued to go from the state to the chancellor’s office and not sufficiently come to the campuses,” she said, referring to several controversies involving Measure B funds, the PCCD, and Chancellor Laguerre.

In April, 2017, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Measure B funds intended for part-time instructors may have been spent on “salaries, vacation, sick leave and other fringe benefits” for non-academic staff.

“It’s an unprecedented opportunity for the district. It’s simple economics.”

— Benjamin Schneider, Eastlake resident

After the report was published, the PCCD agreed to an independent audit to examine the district’s use of Measure B funds, which found only minor missteps in fund management.

But suspicion lingers among many Laney faculty and students.

“Our problem at Peralta isn’t a lack of money,” Student Trustee Nesi More said. “It’s the lack of [the] will to do the right thing.”

The PCCD was investigated by an Alameda County Grand Jury in 2009 amid concerns that the district inappropriately used public funds for travel expenses and questionable contracts.

In 2015, the Solano Community College (SCC) Board of Trustees were also investigated by a grand jury under suspicion of fund mismanagement while Chancellor Laguerre was president of the school.

The jury admonished SCC board of trustees for their handling of public funds, but didn’t find evidence of illegal activity.

Part Two: Community

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Cici Zheng moved to Oakland from Guangzhou, China, 13 years ago. She and her husband own a hardware and lighting store in Oakland’s Chinatown. They and their son Jackson — a Laney College student — live in a three-bedroom apartment nearby.

“The rent has been increasing steadily,” she said in a translated interview. “I only imagine the rent will go drastically higher.”

Even with rent control, Zheng and her family struggle to pay their living expenses each month, and she fears that the stadium will raise prices even higher.

“Since people in Chinatown are making considerably lower than the average [wage] in Oakland, it will make it very hard for people to stay in this community,” she said.

Chinatown Chamber of Commerce member Carl Chan has been a vocal supporter of the ballpark, even appearing in a September promotional video for the stadium.

“Our small business owners are pretty desperate,” Chan said. “We have to do something drastic to keep them around.”

Known as the “Mayor of Chinatown,” Chan runs the real estate firm Claremont Development and sits on the board at Asian Health Services. He says residents are already beginning to move to other neighborhoods. This is “pretty sad,” he said.

Chan says Chinatown has a reputation as a bad neighborhood, and the Oscar Grant and Occupy Oakland protests worsened that reputation by driving away customers from local businesses. He thinks the stadium could “help with the image issue” in Chinatown.

“When there is a ball game there is security and people walking around,” he said. “What we lack now is people walking around at night time.”

But Zheng said that Chan and the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce have little connection to the Chinatown community.

“For the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce to come out and say that they represent local businesses and they want the ballpark to be established in this community is just wrong,” Zheng said.

One of the selling points for the new stadium is that the A’s will build affordable housing with the stadium for area residents.

“Affordable housing” generally refers to housing on which renters spend 30 percent or less of their household income.

Affordable housing is funded by subsidies, bonds, and tax vouchers from various local, state, and federal programs like Section 8 and Alameda County’s Measure A1 Housing Bond.

These programs either assist renters in paying their housing costs or provide tax incentives to builders to provide affordable units.

Wait lists for affordable housing applicants are long.

In Oakland, renters have to apply for lotteries just to get on Section 8 and other public housing wait lists, according to the Oakland Housing Authority website.

If the A’s don’t build enough affordable housing for all of the overburdened renters in Chinatown, renters like Zheng may have a long wait for one of their affordable units.

“We don’t really have a second choice. We’re the A’s–we don’t have a B.”

— Oakland A’s President Dave Kaval

But Kaval said this isn’t the team’s responsibility. “We’re not going to solve Oakland’s housing crisis,” he said.

Over half of Oakland renters like Zheng are overburdened, or spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, according to Affordable Housing Online.

Zheng fears her burden could turn into displacement at the hands of zealous developers if the A’s move nearby, and she doesn’t want to leave Chinatown.

“This is the community I’m nested into,” she said.

Even if she wanted to move, Zheng may have a hard time finding an apartment she could afford.

Oakland has experienced substantial rent increases in recent years. A two-bedroom apartment in Oakland currently averages $2,951 per month, up about 55 percent from January 2011, according to apartment listings website Rent Jungle.

Statistical Atlas lists the median annual household income in Chinatown at $18,400. With that income, “affordable” rent is about $460 per month, almost a sixth of the average Oakland apartment.

So Zheng and other Chinatown residents have good reason to fear for their stability. And if Chinatown’s housing market reacts to the new ballpark as other cities have, her situation could turn dire.

In 2013, online news outlet CityLab compared the cost of living in neighborhoods near baseball stadiums to the average cost of living in their respective cities.

Of the 29 MLB teams studied, the cost of living in 20 of the neighborhoods near those stadiums was more than the metro average, and a third of those neighborhoods cost two to three times more than their respective metro average.

Rumblings in Oakland’s planning commission and city council suggest Zheng isn’t the only one who’s worried about Chinatown’s future.

Earlier this month, Oakland City Councilman Abel Guillén asked the Oakland Planning Commission to introduce interim development controls that would protect Chinatown residents from prospective developments in the area.

The commission passed on the controls to the Community and Economic Development Committee, which reviewed them Nov. 14.

Although multiple council members support the proposal, it was put on hold until more community outreach and a “pro/con analysis” could be produced. The committee will review the controls again Dec. 5.

Under the new controls, developers would have to inform both landlords and tenants of their demolition intentions in several languages, including Mandarin, Cantonese and Spanish.

New parking facilities would be prohibited, and there would be special regulations for hotels and large-scale development in the area. The city council has requested that developments with at least 15 percent affordable housing be exempted from the controls.

Some believe the proposal is lackluster.

“It was weak, now it’s even weaker,” said Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN) Coordinator Alvina Wong. She said the 15 percent affordable housing recommendation was “too low.”

Wong is a leading voice in Chinatown’s opposition to the stadium. She shares Zheng’s fear that many Chinatown residents will be forced out by new developments in the area spurred by the new stadium.

“This is just another carve-out of Chinatown,” she said.

Guillén has also expressed concern about the fate of his constituents in the Chinatown and Eastlake communities, saying many of them have shared their worries with him about the stadium’s impact on housing costs.

“At a time when Oakland is experiencing a housing crisis, this neighborhood and the community as a whole cannot afford to lose more naturally occurring affordable housing,” he said.

Kaval has repeatedly stressed the importance of community input in the process of negotiations between the A’s and the PCCD.

The stadium should be a “win for everyone involved,” Kaval said. But it’s hard to imagine that residents would be able to agree what a “win” looks like if they don’t know what Kaval is saying.

Zheng doesn’t feel comfortable speaking English without a translator.

Data collection website Statistical Atlas reports 87.5 percent of Chinatown residents who speak Chinese don’t speak English “very well,” which would make it difficult for the majority of them to understand what was said at the public engagement meetings.

“At a time when Oakland is experiencing a housing crisis, this neighborhood and the community as a whole cannot afford to lose more naturally occurring affordable housing.”

— Oakland City Councilmember Abel Guillén

Wong wrote in an email to the Tower that, to her knowledge, the A’s haven’t provided translation services at any of their public meetings, and the team hadn’t provided “any real engagement” with the Chinatown community.

“That’s a lie,” Kaval said in a phone interview with the Tower. He referenced an Aug. 31 A’s community engagement meeting hosted by Franklin Elementary School at which translation services were offered.

But the A’s didn’t provide the translation services at that meeting.

East Bay Asian Youth Center (EBAYC) Deputy Director of Policy Initiatives Andy Nelson said his organization provided the translators that day.

“The A’s have never provided translation services at any meeting I’ve been to,” Nelson said.

Kaval said in August that the A’s would provide Cantonese, Mandarin and Korean translators at future meetings, but Wong said she has yet to see those translators.

Chinatown is only one of several neighborhoods that may feel a tighter economic squeeze if the stadium moves in.

Amado Canham lives in Clinton, a neighborhood between Eastlake and San Antonio, just a few blocks from the proposed ballpark site.

He and his father share a two-bedroom apartment with one of Canham’s friends, who was recently evicted and sleeps on their couch.

Canham said most of his family’s income goes to living expenses. Their rent has risen steadily over the years, and he wonders how long it will be before they’re priced out of their building.

Like many residents of the neighborhoods near the stadium site, Canham said he is one of the many who face displacement if the A’s move to the area.

“It’s not a secret,” he said. “When any kind of big money moves in, people get moved out.”

A few blocks from Canham, Benjamin Schneider shares his Eastlake apartment with several roommates. He’s an avid A’s fan, and he can’t wait for the stadium to move to the Peralta site.

“It’s an unprecedented opportunity for the district,” Schneider said. “It’s simple economics.”

He believes the A’s want to “embed their team in a symbiotic relationship” with Eastlake and Chinatown, and said affordable housing and business opportunities provided by the A’s would enrich the area.

Schneider said his loyalty to the Peralta site is dependent on Kaval’s dedication to his promises to build housing for the community.

“The number one focus is affordable housing,” Schneider said. “If [Kaval] backs off of that, I’m not interested.”

Part Three: The Big Picture

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The Golden State Warriors announced last January their plans to leave Oakland’s Oracle Arena for a new stadium in San Francisco. Three months later, the Oakland Raiders decided to pack their cleats and head for Las Vegas.

Both teams will be gone from Oakland by 2020.

Since then, the A’s have run an extensive public relations campaign with the tagline “Rooted in Oakland” to reassure Oaklanders that they weren’t about to lose their baseball team, too.

With one professional team left, some wonder what will happen to Oakland if the A’s don’t get their preferred site. Some believe the team will join the Warriors and Raiders in an exodus from the city.

“If we keep on this path, we gonna lose the A’s,” Oakland resident Assata Olugbala said at a Nov. 14 Community and Economic Development meeting.

Others question whether Oakland needs a professional sports team at all, but most in Oakland want the team to stay.

“I think the main thing is that, as fans of the A’s, we want to keep them in Oakland,” said Rafael Gonzalez of the Laborers Local 404.

President Kaval has an answer for every concern about the new stadium, and many question how far the A’s are willing to go to protect the surrounding area.

“If we keep on this path, we gonna lose the A’s.”

— Assata Olugbala, Oakland resident

Some experts question the ballpark’s economic benefit to the city, and environmental groups are nervous that stadium pollution will drive out the local birdlife and clog Lake Merritt with trash.

But the A’s have also made considerable contributions to the community.

Since 1997, the A’s Community Fund has donated over $1.7 million in grants and donations, and over $1.8 million in free tickets to a variety of organizations in Oakland.

They’ve refurbished Greenman Field park and the Oakland PAL campground, and have contributed to multiple educational organizations. They’ve also worked with local artists to create public murals and design statues.

In 2016, they teamed up with the Raiders and the Warriors to match $50,000 in donations toward the Oakland Warehouse Fire Relief Fund for Ghost Ship Fire victims and their families.

The A’s will celebrate their 50th anniversary in Oakland next year. They’ve made the city home, and they hope to keep it that way. What many are wondering, though, is how far does Oakland have to go to keep the A’s at home?

Local environmental groups have raised concerns about the ecological impact on the area surrounding the Peralta site, particularly Lake Merritt and the Merritt Channel.

“Everything from the Pacific Flyway to the aquatic animals in the surrounding area are at risk,” said Naomi Schiff of Coalition of Advocates for Lake Merritt (CALM).

The Pacific Flyway runs from Alaska to Patagonia, and is an important north-south route for American migratory birds. Herons, Egrets, and Cranes take rest stops along the way as they travel, and Lake Merritt — the nation’s first wildlife refuge — is one of those stops.

Migratory birds struggle to find rest stops due to increased pollution and deforestation in their migratory zone. Now activist groups like CALM and the Golden Gate Audubon Society are concerned that a stadium may pollute Lake Merritt and drive the birds away.

The A’s say their stadium plan is state-of-the-art. A’s Vice President of Internal Affairs Taj Tashombe said at an October Berkeley City College meeting that the new stadium would “rewrite the books” in terms of stadium design.

“Everything from the Pacific Flyway to the aquatic animals…are at risk.”

— Naomi Schiff, Coalition of Advocates for Lake Merritt

He said that if the A’s move to the Peralta site, the studies they conduct will give them the information they need to be as noninvasive as possible.

Tashombe said the stadium could work with the current ecosystem after the A’s finish their investigation, but didn’t offer any details on how the stadium would address issues such as noise, air pollution, and traffic gridlock.

Schiff was surprised the A’s would even need an investigation to see the damage the stadium would cause.

“Debris from the stadium would clog the lake and channel while the fireworks would scare the birds away, resulting in [bird] families dying off,” she said.

Executive Director of the Golden Gate Audubon Society Cindy Margulis has seen firsthand how the current stadium is affecting the environment and believes the new location would be just as damaging.

She says trash from the Coliseum and sediment from the highway pollute the water system.

The Audubon Society’s outreach program educates Oakland’s youth with hands-on experience on the shores of the San Francisco Bay in Oakland.

The Audubon Society conducts restoration projects on the shoreline, cleaning the beach and planting native vegetation.

“A serious problem is trash from the tailgating parties,” Margulis said. A large amount of the trash the Audobon Society gathers on the shoreline comes from the Coliseum, she said.

Margulis believes that if the A’s move to the Peralta site, the stadium would pollute Lake Merritt and the surrounding estuaries in the same way.

In 2002, Oakland voters passed Measure DD, a $198.25 million bond measure that funds improvements to Lake Merritt and the estuary that connects it to the San Francisco Bay.

Celebrations in the Lake Merritt area following the Warriors 2015 and 2017 NBA Finals wins cost the city about $1.5 million, according to an Oct. 2 statement from the Measure DD Community Coalition.

The coalition directs the bond’s funds to causes that benefit Lake Merritt and the estuary.

Their statement lists various concerns about potential environmental impacts the new stadium could have on the surrounding area.

A Golden Gate Audubon Society September press release stressed that Lake Merritt is a focal point in the community.

Loud noise from the new stadium could be “particularly hazardous, panicking birds and sometimes leading them to abandon their nests and young,” the press release said.

An October East Bay Times report found that the PCCD offices sit on top of several toxic plumes in the soil, possibly left behind by underground fuel tanks removed from the site in 1981.

The PCCD has failed to address the issue since 2013, when the Alameda County Department of Environmental Health suggested further study of the soil under the district offices.

Cleanup of the site could be costly, but President Kaval said the A’s could foot the bill.

“Any remediation would be something we would take on if a ballpark was built there,” he told the Times.

Kaval said the A’s are still in the early stages of planning for the new stadium, and more research needs to be done in order to see what the environmental impact of the stadium would be.

“The A’s priority for the Peralta site is that it has to work for the A’s, has to advance the Peralta Colleges and has to protect the community,” Kaval said.

Schiff disagrees.

“The trustees should just say ‘no’ right now,” she said.

Professor Noll is an expert on stadium economics. Regardless of their funding source, Noll said stadiums tend to do very little for a city’s economy.

“Just plunking down a stadium has no effect,” he said, adding that sports teams only bring money into their cities if they build large-scale developments along with their new stadiums.

Without extensive retail and housing additions, “the stadium doesn’t add anything,” Noll said.

A “stadium village,” and affordable housing are part of the A’s stadium plans, but Noll is skeptical.

“Maybe the A’s are dangling a carrot,” he said, suggesting that large-scale developments promised by the team may be no more than a bargaining chip to encourage negotiations.

University of Maryland Economics Professor Dennis Coates doesn’t have high hopes for the stadium either. “Somebody’s almost surely going to lose,” he told the East Bay Express.

“Our problem at Peralta isn’t a lack of money. It’s a lack of [the] will to do the right thing.”

— Student Trustee Nesi More

But who will lose is harder to predict, Coates told the Express, and will largely be determined by the city’s actions to protect vulnerable nearby residents.

Experts like Coates and Noll predict stadium impacts on cities by looking at those that have already been built.

Washington, D.C.’s Navy Yard community became the site of a new baseball stadium — and drastic demographic shifts — when the city announced in September 2004 it would build the Nationals ballpark there.

Construction workers broke ground on the stadium in 2006, and nearby neighborhoods quickly transformed.

The Navy Yard was a predominantly Black neighborhood before the stadium was built, according to the American Community Survey (ACS).

But D.C.-based Governing magazine reports that, between 2000 and 2010, the Black population of the Navy Yard neighborhood dropped 43 percent, and the neighborhood is now gentrified.

The median home value has risen 128 percent in the neighborhoods near the stadium, according to ACS, and the percentage of residents with incomes over $100,000 has nearly tripled since 2000.

Three blocks from Nationals Park, a one-bedroom apartment at One Hill South luxury apartments starts at $2,650 per month — about 30 percent more than the average one bedroom apartment in the city, according to Rent Jungle.

Washington taxpayers paid $670 million for the stadium, a stark contrast to the A’s promise of a privately funded ballpark.

But the neighborhoods near Nationals Park are still similar to what opponents of the Peralta site fear: expensive restaurants, rampant condo development, and a whitewashed version of what was once a community of working-class people of color.

The Washington Post characterized the stadium as an “urban development triumph.” But reports of the Navy Yard stadium as a boon to area residents bear little reference to the predominantly Black residents — now mostly gone — that made a home out of the area for half a century.

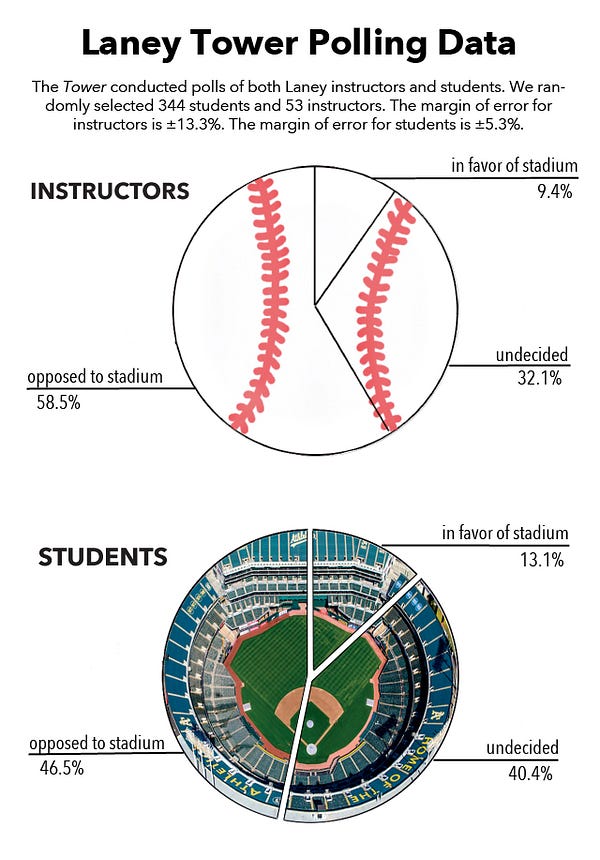

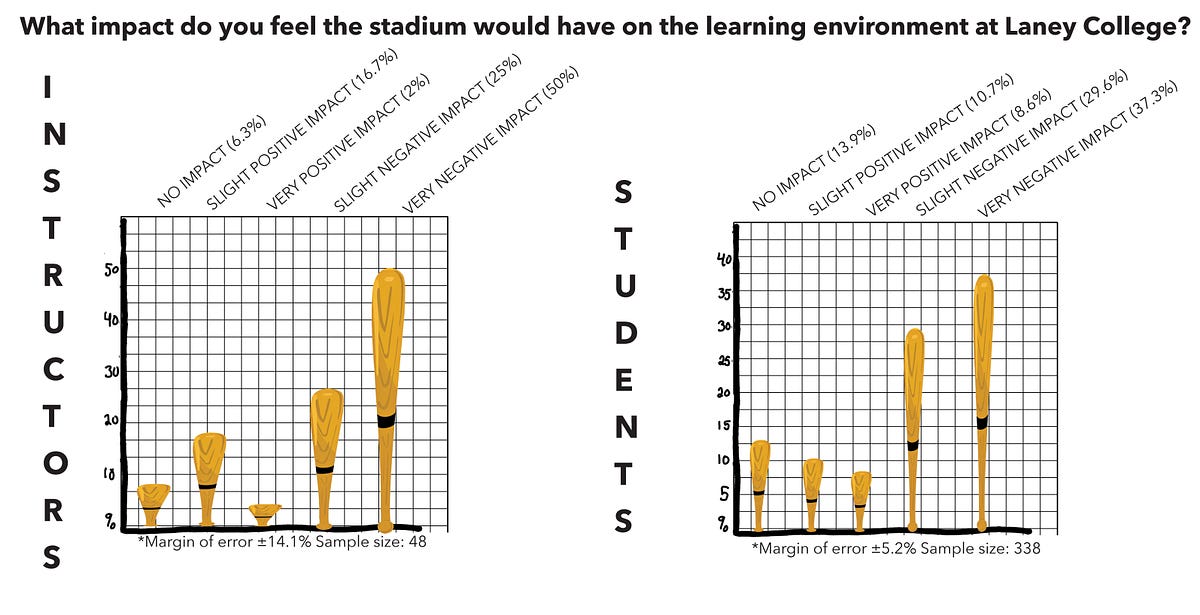

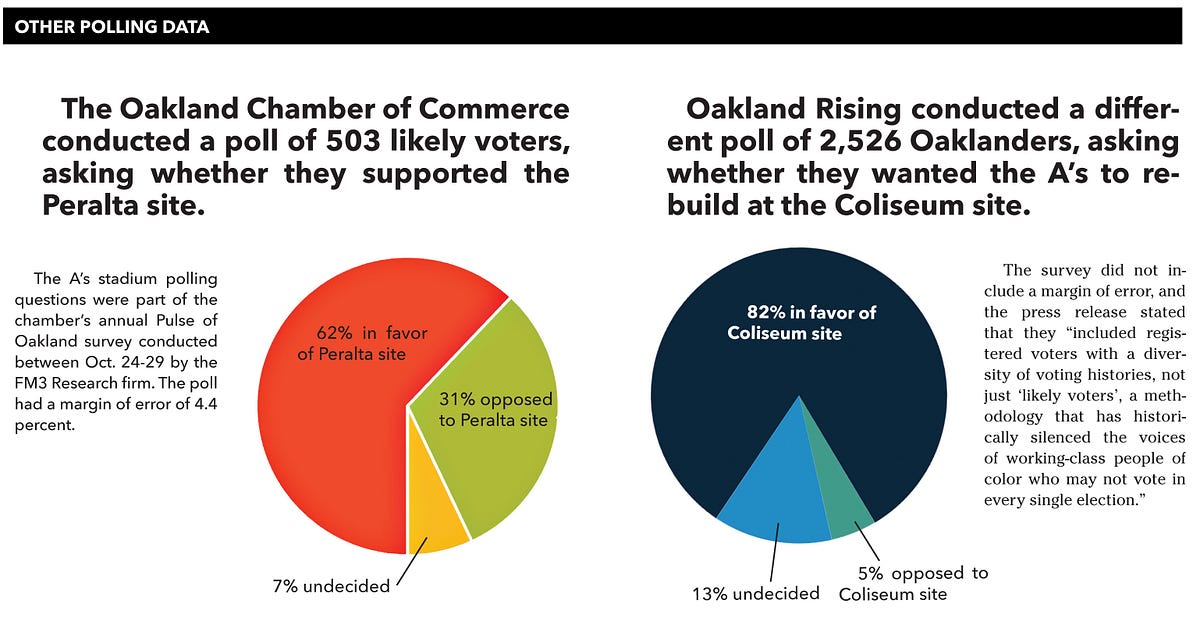

The majority of Oaklanders support the stadium at the Peralta site, according to a recent Chamber of Commerce poll. But the Tower’s poll of the Laney community tells a different story.

The majority of Laney instructors and nearly half the student body oppose a stadium across the street from their campus.

City representatives have expressed lukewarm acceptance of the Peralta site.

Mayor Libby Schaaf said she preferred the other possible locations — the current Coliseum site or the Howard Terminal — because there are “less communities to disrupt.”

Councilmembers Larry Reid and Noel Gallo have both stated their preference that the A’s rebuild at the Coliseum site. But Dave Kaval said the Peralta site is the only one in Oakland where they can privately fund their new stadium.

“We don’t really have a second choice,” Kaval said. “People ask me if we have a Plan B. I say, ‘Hey! We’re the A’s, we don’t have a B.’”

Though the City will be largely responsible for corralling the stadium’s impact, the decision to allow the A’s to build at the Peralta site lies with the Peralta Board of Trustees.

On Dec. 12, the board will announce whether they will enter into negotiations with the A’s. Then the real games will begin.

Written and edited by Brian Howey and Sarah Carpenter. Environmental reporting by Yohana Gebre. Community reporting and interviewing by John Reimann, Argel Brown, and KR Nava. Audio editing and other reporting by Kyiakhalid Ruiz.