by Alice Robinson

The Laney Forum became a center for strategizing and sharing ideas about how to fight a war.

The war has gone on for 60 years, and the battlefield is spread across America’s cities. It’s the war tobacco companies have been waging against the black community, according to organizers.

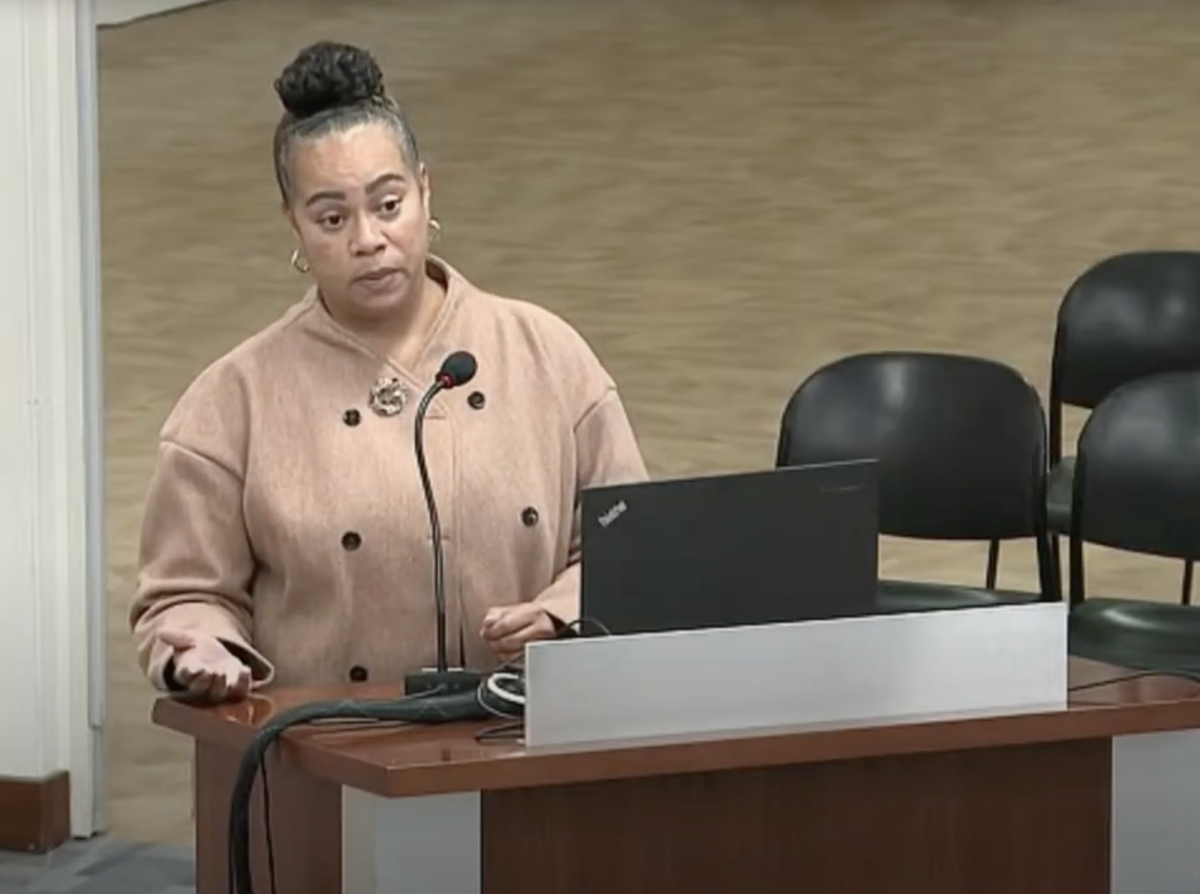

At the April 13 gathering, speakers and a documentary addressed “Black Lives and Black Lungs,” which is the movie’s name. These facts stood out: tobacco companies have launched campaigns to aggressively sell their products in predominantly Black areas for decades and the same companies have intentionally marketed menthol cigarettes toward the Black community.

“Tobacco-related diseases are still the number one cause of death in the African-American community,” said filmmaker Lincoln Mondy in his documentary.

About 20 people came to the event. Panelists were Rakiah Anderson, a tobacco researcher working at Oakland’s Prevention Research Center; Mondy, who spearheaded the film; and Vincent Garrett, a former Merritt College student, now studying at the University of San Francisco, who quit smoking after Laney Tobacco-Less Club President Marlene Hurd talked to him on Merritt’s campus.

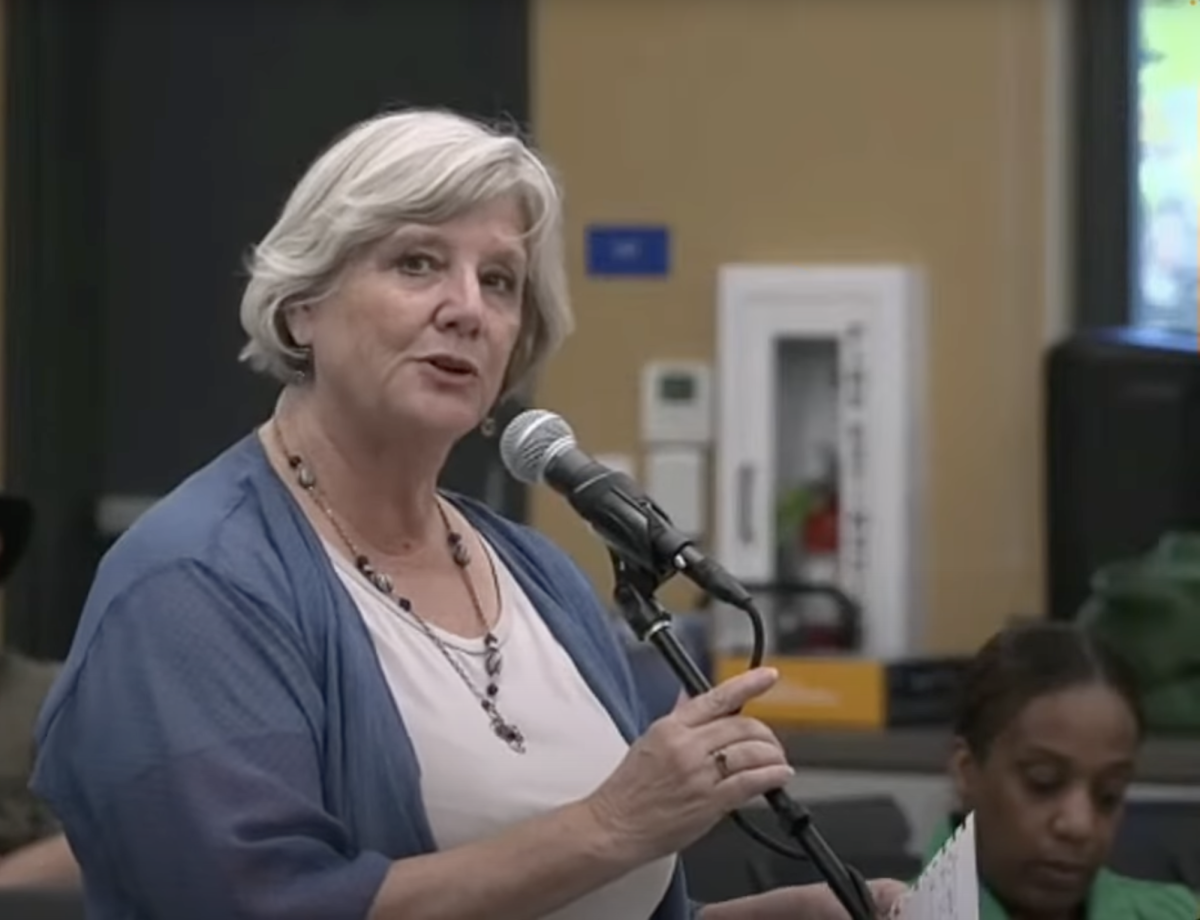

The audience brought just as much passion as the guest speakers.

“I’m 73. I lost a father — who was a Tuskegee Airman — to his pipe,” said MJ Abdul Al-Bari, who has a master’s in psychology. He engrossed other audience members with a passionate extended commentary about the danger of tobacco.

Al-Bari added that when Africans were brought to the United States to become slaves, many were forced to work in tobacco fields. Tobacco companies are “the number-one warring agent against our people,” said Al-Bari.

Several audience members questioned the panel, and one man even stood up and gave a heartfelt “thank you” to the speakers for their efforts to help his community.

Audience members and panelists discussed their anger with black leaders like the Rev. Al Sharpton. Some in the audience said Sharpton and others take money from cigarette makers and refuse to publicly condemn “big tobacco.”

The movie pointed out that some members of the Congressional Black Caucus have received money from tobacco producers.

Panelists talked about the negative cycle of smoking, which is hard to stop. Parent smokers set examples for their kids, making it more likely children will also smoke. The pattern has continued over decades. Tobacco “becomes a virus and it spreads,” once in the community, said Garrett.

An economics student from Merritt College said he came to learn even more about what he considers the racial propaganda from tobacco marketers. “You’ll see it too when you watch TV: you’ll see black people smoking a lot,” said Don, who did not want his last name used. “When you see everything, you have to realize it’s a message they want to put out there.”

Hurd said Laney is technically a smoke-free campus, but she knows people smoke.

“People tell me ‘Miss Hurd, we’re a smoke-free campus, but people still smoke.’” Hurd said she knows of one campus spot in particular. “A couple students told me, ‘they (other students) smoke in the Laney Garden.’ ”

Alice Robinson is a staff writer for the Laney Tower.