The shift from in-person to remote learning has led to an invasion of bots and “phantom students” who are taking advantage of Peralta Community College District’s enrollment system to fraudulently obtain financial aid.

The fraud is causing class enrollment lists to balloon with fake names, creating more work for faculty and administrators who need to identify and weed through the imposters. The fraud also has the potential to impact college funding, and could affect student access to needed classes.

Using a bot—a robotic software program—a bad actor can generate the appearance of a real student by using fake identification to fill out an application form, enroll in classes, and sometimes collect financial aid.

Tracking these fake students, say college officials, is like hunting multiple moving targets, and efforts to mitigate the problem are tantamount to playing whack-a-mole with serious consequences for the district’s administrators, Peralta faculty, and real students who need to enroll.

The recent rash of fraud is a statewide problem that’s been reported in the Los Angeles Times, Inside Higher Ed, and elsewhere. But until now, the extent of the fraud occurring at Peralta—which includes Laney and Merritt College in Oakland, Berkeley City College, and College of Alameda—had gone largely unreported.

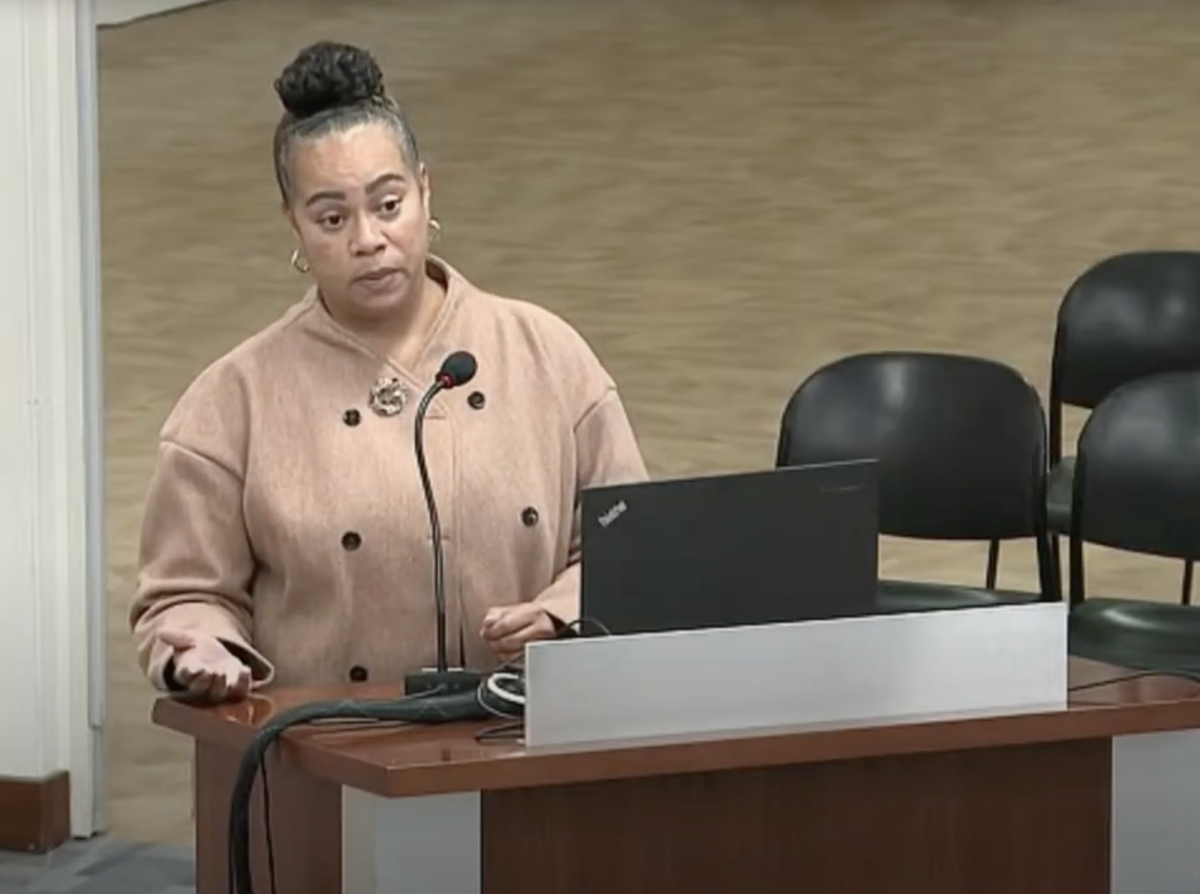

In a June 22 memo, Siri Brown, vice chancellor of academic affairs at Peralta, reported that over 550 fraudulent applications were received for the month of May alone—and 125 of those students were enrolled in 9-12 units of summer coursework in total. Brown reported there were 1,138 fraudulent summer and fall applications. In an August 17 email to the Peralta community, Brown said fraudulent applications were bypassing the CCCApply system “in large batches.”

Brown provided an update at the September 14 Peralta Community College District Board of Trustees meeting and said 3,473 fraudulent applications made it past the CCCApply system, with roughly $179,000 in aid obtained through these efforts. Brown said it has been “very challenging” to get an accurate look at the impact of fraudulent applications on enrollment because the district is still receiving them.

David Johnson, president of Merritt College, put it bluntly in an interview with the Citizen. He said there have always been people “trying to game the system for financial aid” but their attempts were “disorganized.” The latest round of fraud, he said, is “cunning, precise and unprecedented.”

Bad actors must game multiple systems to commit fraud

In order to obtain financial aid, these “phantom students” must defraud multiple systems. They first submit a fraudulent application through CCCApply, the California community college enrollment platform. Then, they enroll in classes they have no intention of attending, and finally they access the federal system by filling out the FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) application to obtain financial aid.

The state’s CCCApply application system is the first line of defense. It is equipped with a spam filter that looks for patterns and particular types of data to flag an application as fraudulent before the bots and bad actors can enroll and receive financial aid. Jennifer Coleman, director of statewide products and programs for the California Community Colleges Technology Center, told the Citizen that the system processes several million applications annually, but once an application is flagged as potentially fraudulent, it is then the college’s responsibility to review those applications.

In a September 3 email to the Citizen, California Community Colleges Vice Chancellor for Communications Paul Feist said that if large numbers of “phantom” students are successful in enrolling in classes “it is not being caught at the CCCApply or college level.”

Feist added that it is “critically important” for the colleges to report back to the state in order to improve the machine learning of the spam filter for fraud detection.

Although the college district provides information regarding patterns and what to look for, much of the fraud detection falls on the faculty to remove non-attending “students” by Peralta’s census due date. This year, that date was September 6.

The pandemic has made fraud easier to commit

Prior to Covid-19 and virtual learning, it was easy to see who wasn’t attending class—the students were not in their chairs. Now, faculty must devise strategies to figure out if the individual enrolled in their class is a person or a bot, then cull through their rosters to weed out the frauds.

Once a student, real or otherwise, participates in a class (by completing an assignment, for example), faculty can’t drop them, increasing the risk of financial aid fraud. If a fake student submits one assignment, it becomes much more difficult to drop them early in the semester. The second and final opportunity for faculty to drop these students is late in the semester, when the attendance roster is due, but by that time, financial aid could already be disbursed.

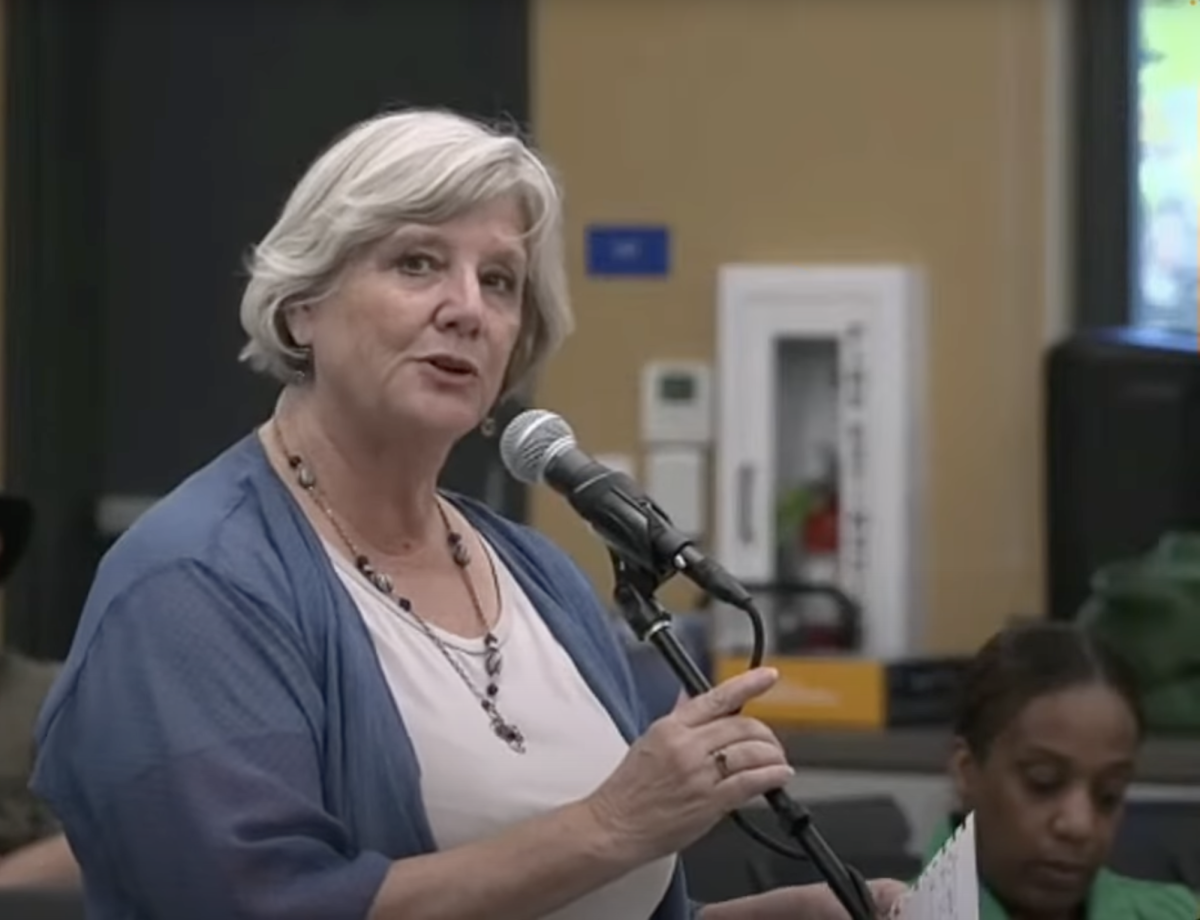

“It’s been a small-scale problem forever that students enroll simply to get financial aid,” Kirsten Olson, professor of anthropology at Laney College, told the Citizen. However, she said that this new wave of fraud has “definitely exploded since lockdown.”

Olson explained that she first noticed a problem recently when groups of students—“five, six, seven, eight, all of a sudden” showed up on her roster overnight.

“There’s a push happening and it’s alarming,” Olson said.

Olson took it upon herself to look into the problem and found herself trying to identify the fake students, worried that they are “occupying a space that needs to go to a real student,” who might be discouraged by a waitlist or won’t sign up at all.

A Laney College adjunct instructor, who did not want to be identified because adjunct instructors, unlike tenured faculty, have no guarantee of employment, noticed during open enrollment that they had “globs” of students with certain things in common. Some had phone numbers with Manhattan area codes or addresses that were the same as homes listed for sale on Zillow. The instructor now gives a short syllabus quiz at the start of class that the bots can’t manage as a way to identify them.

It was “easy to spot them, but time-consuming,” the instructor told the Citizen.

After flagging the potential frauds, the names and student ID numbers are reported to the district admissions and records office, as well as the division dean, who cull through the list manually to determine who could be a fake student.

Once the phonies are cleared from an instructor’s roster, the enrollment number could fall below the official bar to cut the class. The adjunct professor at Laney said they were able to avoid that fate because, fortunately, their dean was aware of the situation and told them the class would not be cut.

Jennifer Shanoski, president of the Peralta Federation of Teachers, the union representing college instructors in the district, indicated that once the census date is hit, the class cannot be cancelled “no matter what the enrollment is.” However, if the fake students are identified and removed before census and enrollment drops below 25, the class could be canceled.

Widespread fraud is harming students and faculty

Merritt College President Johnson calls the spike in fraudulent enrollment “dispiriting” and acknowledges the psychological impact this has on faculty who think they will have a fully engaged group of students only to see a “mirage.”

Blake Johnson, history instructor at Laney College, reported in an email to the Citizen that he had 66 fake students enrolled in his class on August 31. On September 3, he had 94. All of Johnson’s classes were listed as full at the beginning of the semester.

Johnson flagged these “students” because they’d signed up for the same class using sequential student ID numbers. Johnson, like Olson, was concerned that these fraudulent cases would have a “hugely negative impact on access to classes.”

It isn’t just about the schedule of classes, Rudy Besikof, president of Laney College, stated in an interview with the Citizen. Losing access to a class can severely impact a student’s ability to reach their larger educational goal.

When it comes to the question of cancelation, Besikof said, “Our biggest consideration is—are those student paths intact?”

Rebecca Opsata, vice president of instruction at Laney College, echoed Besikof’s sentiment.

“It’s heartbreaking if we keep students who have educational goals out of classes,” Opsata said. When there are fewer students in a class, Opsata remarked, there “is less opportunity to learn from others.”

As the faculty union president, Shanoski said she is concerned that enrollment will be much lower than expected and that next year’s scheduling by the administration will be “based on falsely low student numbers.”

Enrollment at Peralta has dropped precipitously in recent years. For 2019-20, enrollment was at 17,416 full-time equivalent students. In 2020-2021 the number dropped to 14,294 and is currently 7,306 for 2021-2022.

Enrollment was affected by the pandemic, but an influx of bots and frauds exacerbates the concern. Johnson explained that these fake students skew the data and make it difficult to assess if Peralta is serving intended populations or not.

Merritt College is applying to become a Developing Hispanic-Serving Institution. To qualify for this federal grant, the college must have at least 25% full-time equivalent students who are Hispanic. Johnson explained a scenario where the colleges could be suddenly flooded with 2,000 fake student applications in which race or nationality is not disclosed. A situation like this could alter total student demographics and potentially change a college’s “agency status,” putting funding at risk.

The state, district, and faculty are working together to stay ahead of what Johnson refers to as a “particularly pernicious” problem. He said he is “pleased with what the district has done to support the colleges,” and keep the community apprised of their efforts to “bring them into partnership.”

Shanoski, the union president, said that since the administration is in charge of enrollment, enrollment management, and admissions, “this is really an administrative failing.”

It’s not yet clear what the solutions are

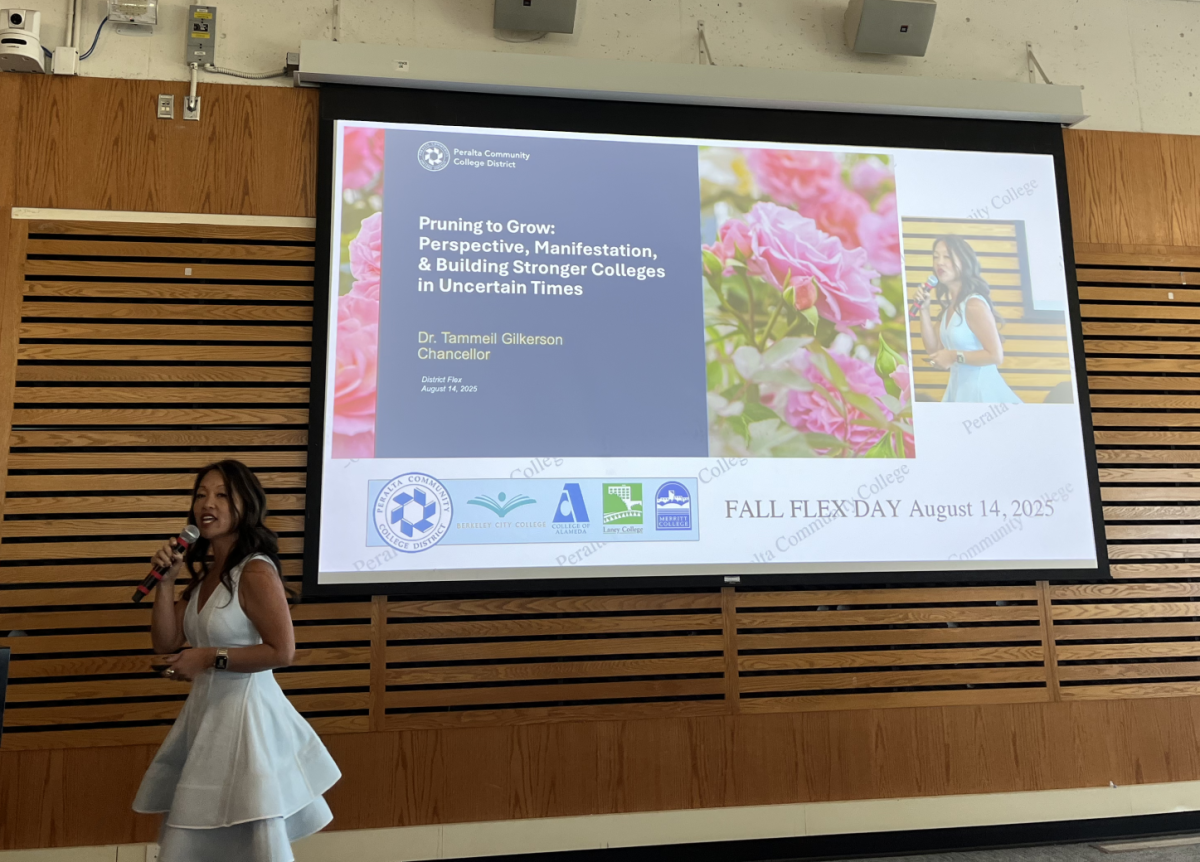

The state updated the CCCApply system with a new bot-detection system on July 15, and plans to further enhance the security of their system this fall, according to an August 30 memo from Valerie Lundy-Wagner, the interim vice chancellor of digital innovation and infrastructure for the California Community College Chancellor’s Office.

The state will now collect monthly information on enrollment and financial aid fraud. Previously, this had been the colleges’ responsibility, along with reporting any suspected financial aid fraud to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Inspector General according to Title IV requirements. Confirmed financial aid incidents, and the value of the aid returned due to fraud, will also be collected monthly.

The Citizen also reached out to Amanda Lim, financial aid systems technology analyst at Peralta, for clarification regarding how much financial aid had been given to fake students, but she did not respond by the publication date.

When asked a similar question, Antoine Mehouelley, Peralta’s chief technology and information systems officer responded, “I will defer all media inquiries to Mark Jackson (sic) (PIO) per district protocol.”

Brown responded via email through Mark Johnson, executive director of the department of marketing, communications, and public relations.

“We are currently managing this issue and it is taking up a great deal of staff time. Once we are through the immediacy of the challenges the fraud has created, we will provide a full summary,” Brown wrote.

This article was reported by Pamela Rudd of The Citizen, and cross-published on The Oaklandside, a local publication devoted to community reporting and investigating the systems that delineate our lives.