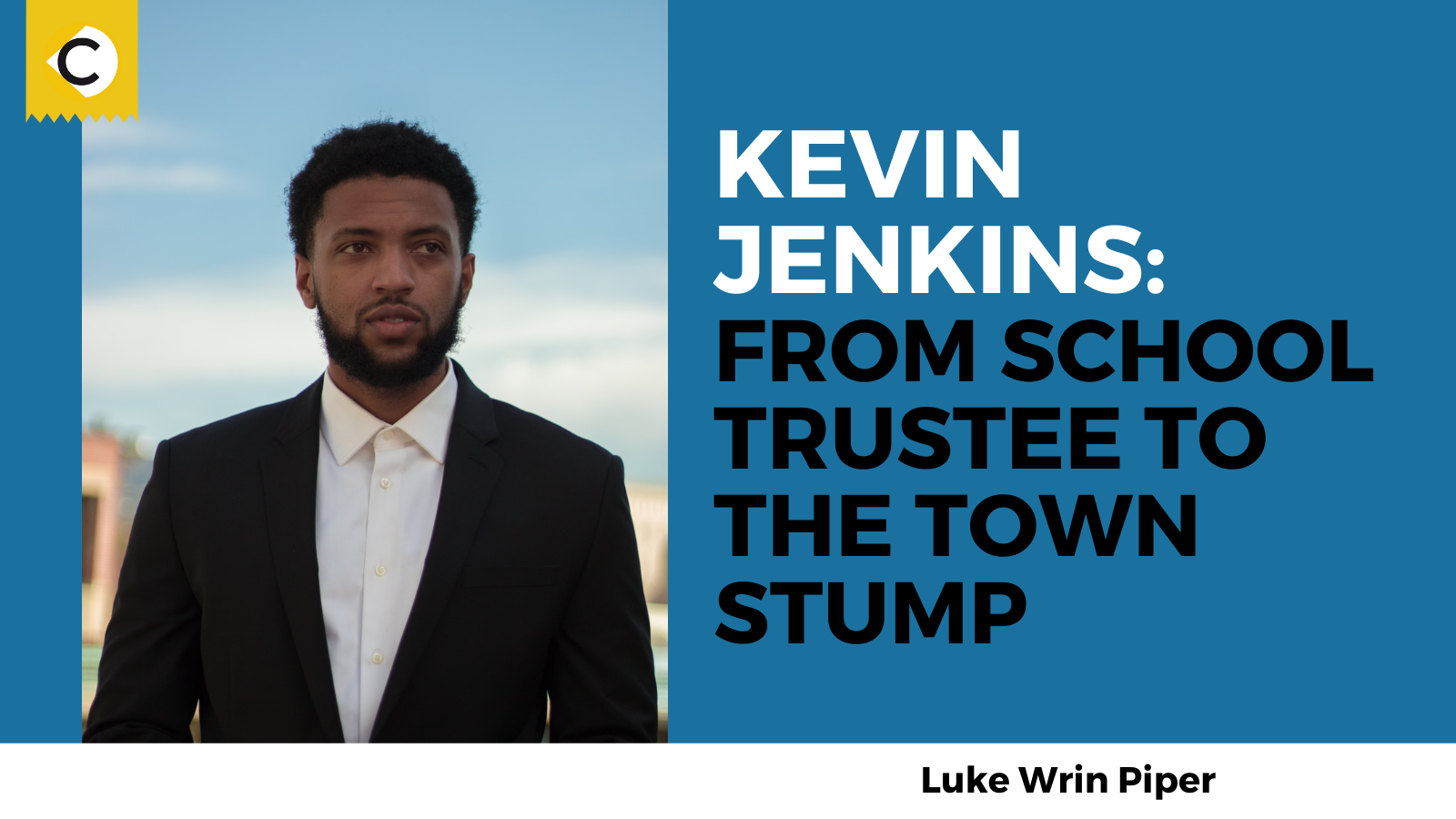

Kevin Jenkins is a dangerous kind of elected official – he is both young and experienced. He is the kind of leader that can leave a room full of students feeling heard; who is unassuming and approachable, but whose bevy of ideas for what-life-could-be never seems to waiver, shrink or acquiesce.

But all of that will be put to the test as he takes the greatest step of his political career by running for the District 6 seat during November’s Oakland City Council election.

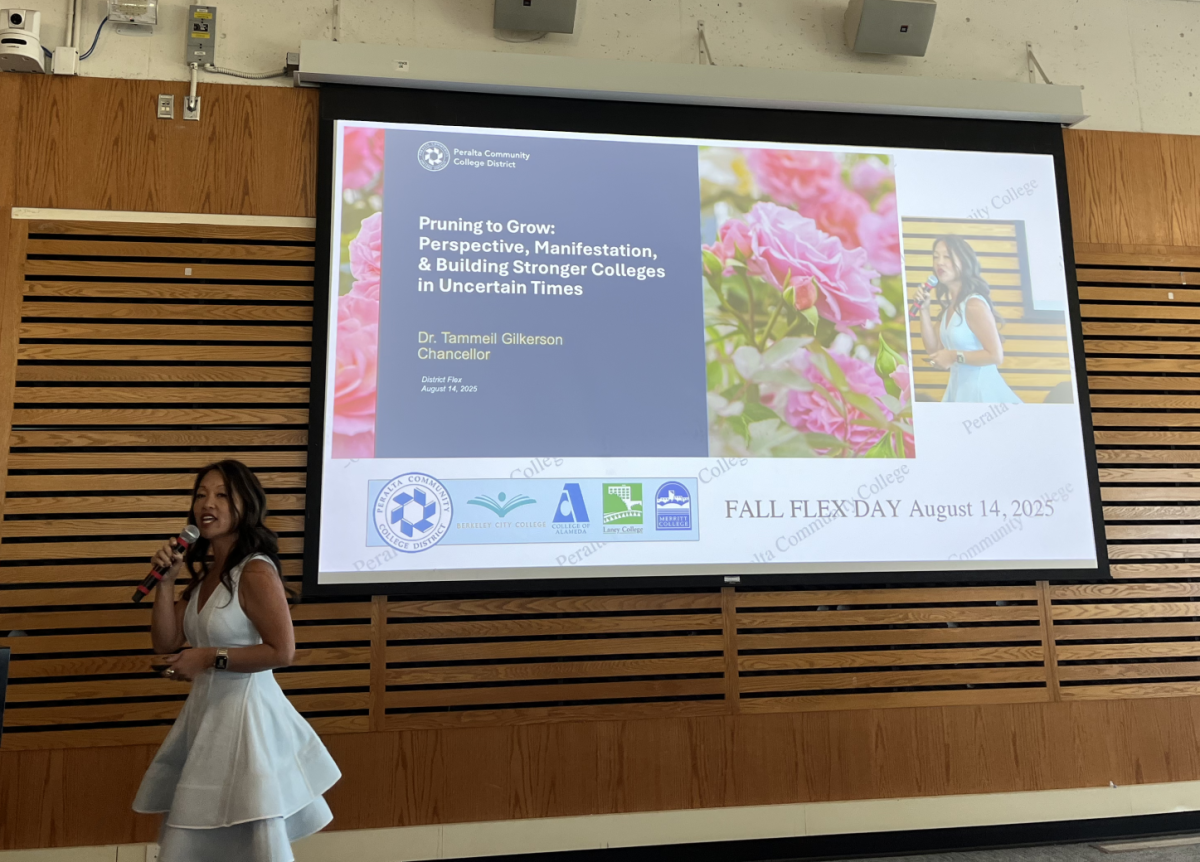

Jenkins is a 35-year-old East Oakland man who in his short life has managed to earn a master’s degree in public administration from California State University East Bay, has served a stint as Alameda County Public Health Commissioner, holds a seat on the Peralta Board of Trustees and serves as president at the California Association of Black School Educators, though he maintains his greatest pride springs unquestionably from being a father to his seven-year-old son Elijah.

While he has been on the Peralta Board for just over a year, he is setting his sights on what would be the most consequential challenge of his life, and the first elected position for which he will face any opposition.

Jenkins, who is an alumni of the Peralta district, would be representing the area of central East Oakland stretching from 86th Avenue to 51st Avenue and sitting between Highway 17 to the south west and just past MacArthur Boulevard to the north east.

Everything that Oaklanders have collectively struggled through over the years is felt in its extreme form in East Oakland.

Violence in its most serious and traumatic forms has been on the rise. Housing and food insecurity has compounded from one generation to the next. While on the most visible surface, illegal dumping has left sections of East Oakland feeling unsafe to many residents. But for all the obstacles standing between East Oaklanders and an improved quality of life, Jenkins explained that it remains one of the most distinctive and resilient communities in California.

The Black Cultural Zone (BCZ) Collaborative Partners is one example of those bonds; a genuine East Oakland phenomenon dead-set on centering the success of Black residents and keeping Black people in Oakland.

In response to generations of Black business owners and artists being underfunded, unsupported and displaced, the BCZ Collaborative is responsible for, amongst other things, the Akoma Market at Liberation Park, which hosts Black businesses, art and community organizers.

The BCZ Collaborative is “focused on implementing arts and cultural strategies and engaging artists and community members in art activism” within a “community development framework”.

Current District 6 Councilmember Loren Taylor is credited with helping to launch the collaborative space and has been an ardent spokesman for the project, which has quickly become a neighborhood institution.

Taylor announced he is running for mayor in September, a position held by Libby Schaaf since 2015, and if Jenkins’ campaign is successful, he hopes to carry the spirit of the BCZ into more spaces throughout Oakland.

Jenkins speaks about community action a lot, every chance he gets. Born and raised in East Oakland, he attended local schools and witnessed the changes of the last few decades first-hand as they happened to him, his family and his neighbors. His bid for city council will bring him closer than ever to having a significant hand in deciding how that change occurs.

“You have to be efficient and a collaborator to be able to get things done,” Jenkins said about his experience in elected office so far, one that is beset with inherent limitations.

“At Peralta, none of us have any power individually. You’re only as good as having four votes. And so that’s a skill in having collaboration and good relationships and understanding the ideals and values of your colleagues.”

Since the Peralta Board of Trustees began conducting meetings via Zoom, Jenkins has been joining his peers from his home in East Oakland. He sees the area as being “the last area that hasn’t been gentrified”, a sentiment he shared in an interview in April 2021 on the podcast The Black Landscape hosted by Adréa Spearman, who is also a Peralta alumni.

In their conversation, Jenkins said he thinks gentrification “happens not because people want to just move to Oakland–things change. We have more available, and those are all policy changes allowing for more bars, allowing for more bike lanes, allowing for wineries in downtown Oakland. So all of those policy changes have effects long term – that’s interesting to see how they take place 10, 15 years from now,” Jenkins said on the podcast.

“When the bike lanes come, you know things are about to change.”

Jenkins explained that how redevelopment and community improvements are handled in District 6 is paramount.

“We’ve got to make sure that the community has a say in what it is that they want there. We can’t just make the decision at City Hall. It has to be participatory governance for sure,” Jenkins said.

Co-Trustee and friend Dyana Delfín-Polk believes what sets Jenkins apart from other electeds who run on enacting policy and developing accessible housing is the real-life experience he brings to the table.

“I think that that’s what’s on his heart,” Polk said. “It’s a big piece of what I hope will work for him to become successful in his bid for council.”

Polk began serving as trustee the same year as Jenkins, and she said he made it known that creating student housing was at the top of his mind, citing the immediate need for housing amongst Peralta students and the sprawling parking lots at Laney and Merritt colleges that could potentially be repurposed.

Speaking with The Citizen, Jenkins revealed that the Peralta District is currently working on applying for funding through the state’s Senate Bill 169, which allocated $1 billion for community college housing.

“You have to lead with: ‘That is a red line for me that I am not willing to cross.’ You also have to stop people from falling into the cycle of homelessness. Once people fall into that cycle, it’s hard to get out,” Jenkins said.

The nature of governing bodies (like trustee boards or city councils) is that decisions are made by majority consensus, something which Jenkins has been learning to navigate during this last year at Peralta.

“We’re really limited in what we can do. No one person has any authority, we have authority as a board, as a group,” Jenkins said. But he is confident in the relationships he already has with some of the most consequential public servants in Oakland and his ability to develop further relationships will turn platforms into praxis.

Jenkins felt similarly stifled during his time as Alameda County Public Health Commissioner, which ended in August 2020, six months into the pandemic. August turned out to be the worst month yet for Alameda County until the end of 2020, with reported daily cases peaking at 665 just a week into the month, and the 7-day average of new cases reaching 345 two weeks in.

His time as public health commissioner demonstrated to him how meaningful public positions can be, something he took with him to the Peralta Board a few months later. “I try to get the lesson the first time and not have to continue going through that challenge. As far as the board, I don’t think there’s a vote that I’ve cast that I’m not okay with now,” Jenkins said.

The educational institutions of Oakland have been a constant throughout Jenkins’ life. The son of an Oakland Unified School District teacher, Jenkins sees the recent decision to close several OUSD schools as indicative of a larger problem.

“The parents deserve a fair process. The students deserve a fair process. And I think that this fight has just begun,” Jenkins said.

“People are motivated, people are angry, and they’re justifiably upset with the way that the process has taken place.”

Jenkins believes in the need to see the experience of young Oaklanders in their full forms, and not simply a collection of pieces. He advocates for a holistic approach to solutions.

During his interview with The Citizen, Jenkins repeatedly made clear that illegal dumping is one of the major issues which he hopes to address. “Illegal dumping is a pressing issue in District 6. Kids are walking over mattresses and illegal dumping to get to school. When you normalize that in the child’s brain, what does that do?” And while dumping may be an issue which has no true push-back, the larger inequity of East Oakland is more complex, with plenty of power and money on the side of developers and distributors who do have the power and will to affect outcomes in the neighborhoods.

But many Oaklanders aren’t waiting on institutional change, and are taking it upon themselves to community organize and initiate trash cleanups. One of whom is John Jones III, who Jenkins believes to be someone who is aggressively pursuing justice work in the town. Jenkins spoke about Jones, saying, “John Jones III is a really dynamic activist. He has historical perspective, he has lived experience and common sense approaches to solving these deep rooted issues.”

Many of Jenkins’ concerns are the same ones shared by his neighbors. Speaking of District 6 in a more systemic sense, another one of Jenkins’ platforms is access to food and banking services.

“So it’s a food desert and there’s no major grocery store in the district. So we have got to make sure that people have access to quality foods. It’s also a banking desert. We’ve got to make sure people have access to lending institutions for the city as a whole,” Jenkins said.

If elected, he would be leaving the Peralta Board of Trustees halfway through his four-year term. Jenkins maintains that his purpose is to represent communities he has been a part of, first by being trustee of the Peralta Community College District where he first went to college, and now potentially as a council member representing the area he has lived in for the majority of his life.

In January, Jenkins became president of the California Association of Black School Educators (CABSE), an organization that seeks to advance equity for Black students in the state.

“I want better outcomes for Black children. I mean, it’s real plain and simple: better outcomes. The outcomes are not where they should be. And we have a coalition of advocates that are advocating for that for Black students,” Jenkins said.

Looking to the future, Jenkins sees the East Oakland of 2030 or 2035 as one that’s clean and safe and is a place for what he describes as “development without displacement.”

“I can’t stress that enough,” Jenkins explained, going on to say that the displacement of one Oaklander is one too many.

“I hope that the development around the Coliseum will lead towards more restaurants or grocery stores and a better quality of life for the residents of East Oakland,” Jenkins said.

In an era where nothing can stay the same for long, significant changes are undoubtedly on the horizon in one form or another. The years ahead could be some of the most consequential for Oaklanders in every corner of the town, every neighborhood and corridor and attendance area.

Underneath the platforms and aspirations Jenkins stands on, the shared understanding is that our elected representatives must speak for best interests–but that we must always push to speak for ourselves.