Every semester, incoming Journalism students are instructed to find articles from archives, the internet, or anywhere else they can think of to search for news about the wider Peralta Community College District (PCCD). The goal of this exercise is to assess the ability of each student to gather information about a specific subject. The challenge of the exercise is to find an article that the instructor has not encountered before.

I set out to find as obscure an article as I possibly could about PCCD. I decided to rely on google newspapers in order to track down something that had been digitized from print, rather than relying on online articles.

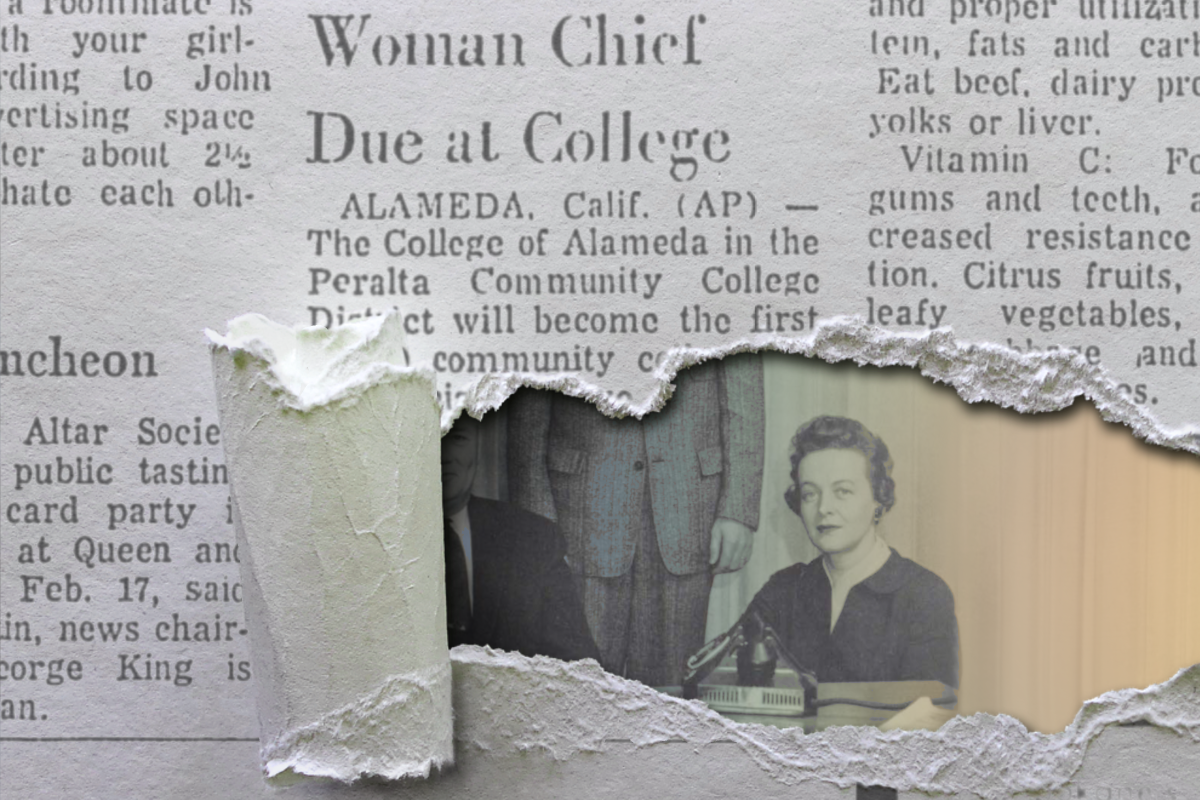

I came across a small column in a 1975 issue of The Spokesman Review, which read “Woman Chief Due at College”. The article is only three sentences long. It states that Dr. Jeanette Poore, President of Everett Community College at the time, would be the first female community college President in California.

There was nothing more to the article. I was positive that no one had found this and brought the article to class. I was promptly asked if I would be interested in doing a deep dive into this forgotten character.

My search began with several secondary sources that I unearthed. The first was an obituary, published by the college that Poore had served at for most of her life, Everett Community College (ECC). The second was an “Alumni Spotlight”, also published by ECC, wherein ECC alumn Conrad Thompson mentioned Poore as one of his mentors and greatest influences.

In a desperate move, I spent five hours at the Laney College library, poring through every digitized edition of The Laney Tower, the original student-run newspaper for Laney College before it rebranded as The Citizen in 2019. After hours of coffee, red and itchy eyes, and possibly carpal tunnel, I came up empty. Not a single mention or hint of anything to do with Poore turned up.

I stopped by the College of Alameda library to try and scour old newspapers there as well, only to be told that I would need an appointment with the head librarian in order to view any. I reached out via email and phone, but received no response back from said librarian, leaving me with not much more than when I started.

According to her obituary, Poore was an advocate for education and equal opportunity throughout her life. She and her twin sister, Jeanie, were born in Centralia, Washington on Jan. 22, 1924 — just four years after the ratification of the 19th amendment that denied discrimination in voting based on sex. Poore completed her high school and community college education during the Great Depression and throughout World War II. She received a Bachelor’s Degree one year after the end of the war in 1946.

After graduating, Poore began her career in education as a counselor for the Snohomish and Moses school districts at a time when it was rare for young women to pursue a professional career in most fields.

Poore first came to California to attend UC Berkeley for her Master’s in Education, which she would complete at the University of Washington in 1957.

In 1958, Poore became a social sciences professor for Everett Community College in Washington state. Poore rose the ranks from registrar to Dean of Students and finally college president.

Most of these dates were extrapolated from off-handed comments in her obituary, birthdates, and death dates. The obituary claimed that Poore had had no children, and her only living family were two nephews living in San Diego. I attempted to reach out to two individuals who fit the correct ages, names, and locations of these surviving nephews, only to receive radio silence in response.

The most unexpected source that I came across during my search were digitized yearbook editions from ECC, which helped with finding not only what roles Poore held throughout the years, but also provided pictures!

In a last ditch effort, and with no small amount of desperation, I went back to the “Alumni Spotlight” on Thompson that Everett had published, hoping that a way to reach him might be listed on the site. None was available, and Poore is only mentioned very briefly within the article.

With my hope and time dwindling, I googled Conrad Thompson. Desperate times and such. The first link that appeared was his LinkedIn. Thompson was listed as a volunteer for an anti-drunk driving campaign in Snohomish County, Washington, but not as active in any other activities. I called the Target Zero DUI Task Force hoping to leave a message, only to be told that Thompson had retired from volunteering.

It was at this point that despair finally reached me. I sat on the floor of my newsroom, gazing up at the ceiling, wondering where I had gone wrong. In taking the story? In looking for my sources? Or was finding the article in the first place the catalyst that had launched me down this Sisyphean journey towards madness?

As I sat staring at my laptop, drafting emails to my Editor in Chief begging for mercy, a voicemail appeared on my phone with a Washington area code. An even-keeled voice called from over the phone, “Hi, this is Conrad Thompson. I hear you’ve been looking for me.”

Thompson, now 79, met Poore during her tenure as Dean of Students at ECC when he was 17 years old. He recalls that her influence changed the trajectory of his life forever and inspired him to pursue a career in public service.

Thompson dropped out of high school in the ninth grade to support his mother and three younger brothers at home. He later joined the army for the free college education benefits. However, he had been denied funding for his education at ECC on the basis that he had not yet completed his high school education requirements.

In urgent need of support and help, Thompson was introduced to Poore.

“She was a nice lady. Very soft spoken,” Thompson recalled. “I explained to her what my problem was and she said ‘I’ll take care of that. I’ll schedule you to take the GED.’ So I took it and I passed. That allowed me to get the schooling I wanted in the military.”

In light of this great opportunity, Thompson dedicated himself to student life at ECC, holding positions such as Vice President of the Associated Men’s Student and Student Body President. He even ran a talent show or two.

Following these achievements, Poore called Thompson to her office to tell him how proud she was. As Thompson remembers, she told him, “You know Conrad. I expect great things from you, and I am confident that you’re going to do them.”

Thompson eventually went on to receive his bachelor’s degree from Western Washington University and decided he would also pursue a Master’s degree at Seattle University.

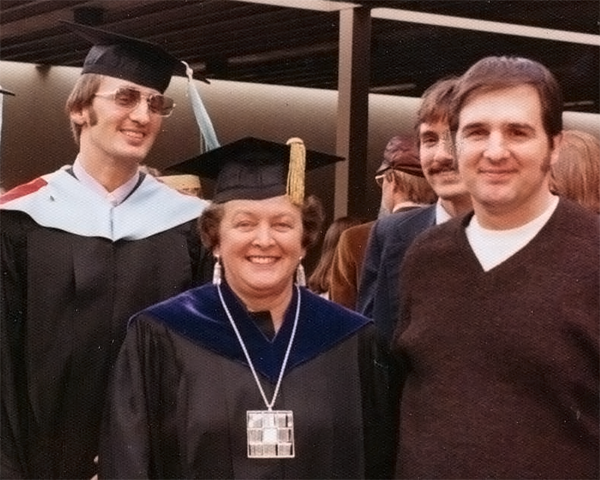

At his graduation ceremony for his Master’s, Thompson remembers other students walking down the stage to receive their degrees from the college president. However, when Thompson walked up to be handed his own degree, the president stepped back to make way for Poore. At the time, Thompson had no clue that she was on the Board of Directors for Seattle University or that she would be handing him his degree. This heartwarming moment was the last time that Thompson would ever see Poore.

I felt that this conversation had shifted something for me. Before this conversation, Poore was a ghost, made up of a collection of random dates and times, cruising through academia in two different states and leaving behind little more than a three sentence article in a newspaper. However, after my conversation with Conrad, Poore was a woman with a smile, with commitment and kindness.

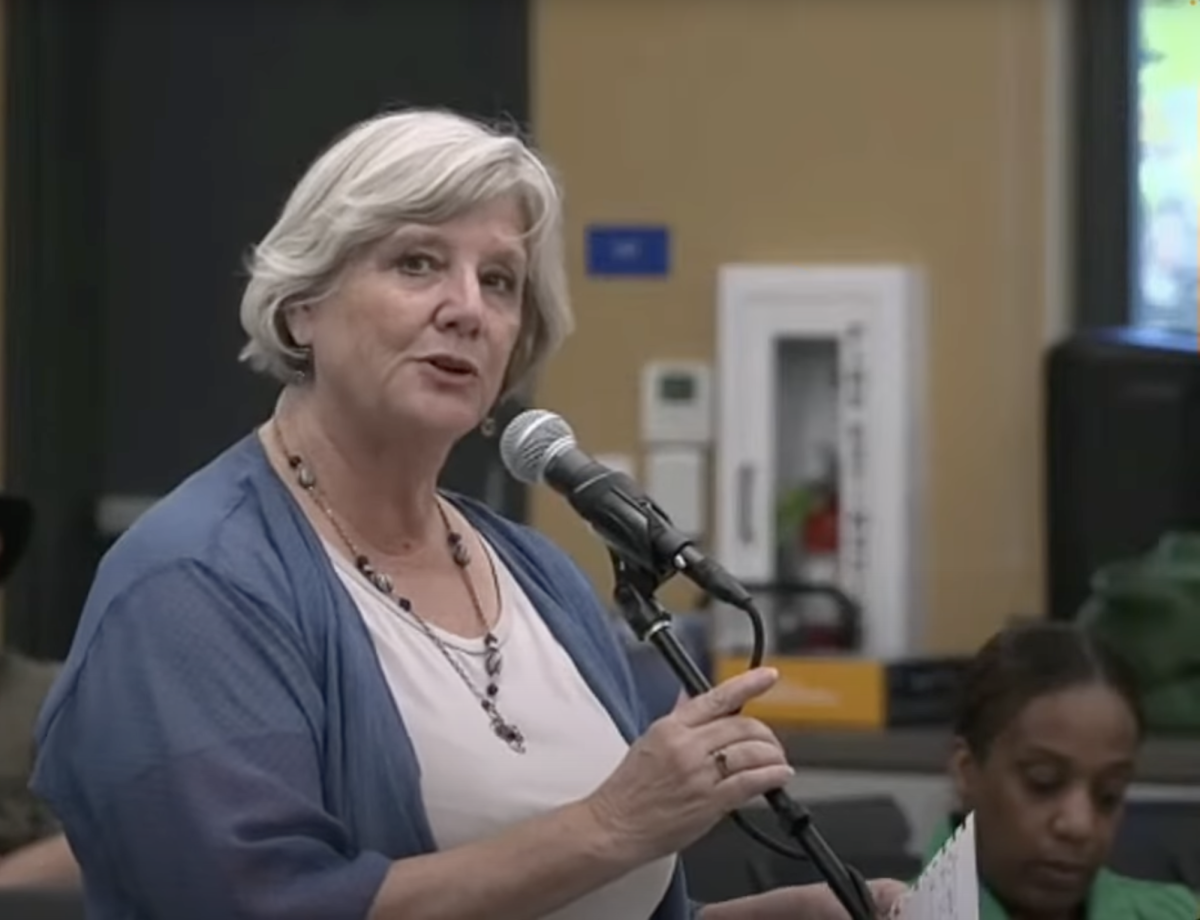

Poore served as President of ECC for five years before leaving to accept the role of President at the College of Alameda. She made history as the first female community college president within the Peralta Community College District and the first female community college President in California. She served the College of Alameda community for six years before finally retiring back to her home state.

According to her obituary from 2000, Poore’s involvement within her community continued well after retirement. Poore served on the National Board for the Camp Fire Girls, a youth development non-profit which was one of the first inclusive organizations for young girls geared towards developing essential skills for adulthood. Poore received the Luther Halsey Gulick National Camp Fire Girls Award in 1969. Her involvement with this organization was a common thread throughout Poore’s life.

Thompson still attributes the many successes of his career to Poore. In a follow up interview, Thompson mentioned that he had been able to testify in a Special Committee on Aging by the United States Senate on May 21, 1986, while he was the Director of the Washington Bureau of Nursing Home Affairs in Olympia Washington. This committee aimed to address reform in the nursing home industry following a troubling report showing 50% of nursing homes in the United States had been cited for abuse of their patients. Conrad’s testimony presented ways to improve the care provided, and how to ensure safety for our aging country.

“None of that would have happened without Jeanette Poore,” Thompson recalled. I remarked to him that Poore seemed like an incredible woman. He concurred. “She definitely was.”

Lori Palmquist • Sep 23, 2024 at 10:29 am

Stellar article, Romi! It was a delight to read about and celebrate this amazing woman. I got choked up at the part where she presented Thompson with his degree. What a beautiful gesture on her part.

Laura • May 23, 2024 at 10:31 am

Thank you for your dedication in researching this. Wonderful piece that is greatly appreciated.

Betty Frias • May 21, 2024 at 10:03 pm

Very interesting to learn about Jeanette Poore’s background. Thank you