As another round of budget cuts looms ahead, disabled students at Laney College fear their needs will be forgotten.

“[Disabled Students Programs and Services (DSPS)] is the last man on the totem pole,” says Instructional Assistant Kim Cael.

Cael is referring to how low of a priority DSPS is considered at Laney College. “It’s like that child left in the closet.”

DSPS Coordinator Marion Martin says the cuts began in 2003 and ever since then the program has been short staffed. It used to be that all students who needed accommodation on exams such as extra time could take their tests at the DSPS.

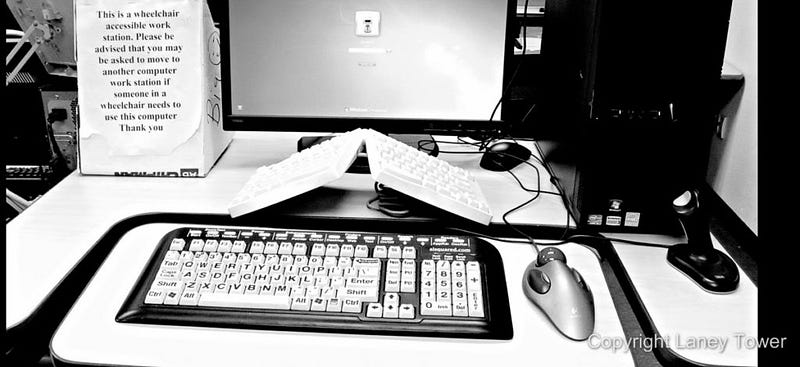

No more. DSPS does provide testing space in the high tech learning center for students who need special software programs.

DSPS does provide testing space in the high tech learning center for students who need special software programs.

Otherwise, there is only one room that can be put to use as a dedicated test space. One part-time proctor, Joe Cha, who doubles as a tutor for the program, also manages the DSPS website.

Karen Talbot, the learning disability specialist, is stretched thin, although she refuses to complain. She teaches two classes that meet twice a week, and she meets extensively with students who want help. In addition, she does all the student assessments, more than 30 per semester, each one a lengthy process.

The Ins and Outs

By law any student with a documented disability is entitled to appropriate accommodation, such as note-taking or extra time on exams.

The DSPS counselor works with the student to figure out what accommodation is needed and together they fill out a standardized form that states briefly what special help the instructor needs to give the student.

For reasons of privacy, the nature of the student’s disability is not specified on the form, only the accommodation required. The student then presents this form to the instructor.

Bad Communication

The Laney DSPS gives its faculty no education about the law and no advice about how to help its disabled students. The terse direction on forms are the only communication the instructor receives about what he or she is supposed to do.

At Laney, it’s up to the student to explain the law, the need for accommodation, and anything else that the teacher might not understand. This doesn’t always go smoothly.

“You just have to talk to your instructor,” says Alisha Alston, a student using the high-tech center, “if they’re able to listen.” But as Martin notes, “it’s the institution’s responsibility to follow the law.”

She notes that the DSPS has not had any civil rights complaints for three years, a good record considering how little resources they are given. “The faculty?” she asked rhetorically. “That’s something else.”

It’s true that there have been complaints against some instructors. One teacher allegedly told a student, “I can’t help you.” But this may have been due to a lack of help from the experts.

Faculty Handbooks

Each of the other Peralta Community Colleges provides a faculty handbook with information and guidance for their instructors.

The most user-friendly is College of Alameda’s, which is easily accessible from its website. It contains a complete explanation of the relevant law, as well as links to commonly asked questions, definitions of qualifying disabilities, and a thorough appendix.

Examples of some commonly asked questions: “Is Extended Time on Tests Unfair? Are Faculty Expected to Accommodate Disruptive Behavior? What Do You Say After You Say Hello? A Guide to Disability Etiquette.” The handbook can be accessed at http://alameda.peralta.edu/dsps/dsps-faculty-handbook.