by Sarah Carpenter

The world is ripe to revisit Anita Hill’s story — and to catch up on where her story has gone.

Young women today are too young to have watched the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in 1991, but they may know Hill’s name anyway.

She testified at these hearings about the sexual harassment she experienced while working for Thomas at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Thomas was confirmed — by the narrowest margin of approval in over a century — and continues to serve as a Supreme Court justice.

In December 2017, Hill was asked to lead the Commission on Sexual Harassment and Advancing Equality in the Workplace.

The commission was spearheaded by women in entertainment, and seeks to correct the industry’s issues, thrust into the spotlight by the #MeToo movement.

Their second meeting is this month.

“When you have a culture that supports harassment, it also supports other kinds of biases,” Hill said. “We’re going to be looking at all of the ways that under-represented or marginalized communities are kept from having equal opportunity and equal outcome in the entertainment industry.”

Hill has said that coming forward with the allegations in 1991 changed the trajectory of her life. Since that hearing, she has leaned into that trajectory and used her platform to continue the conversation around sexual harassment in the workplace.

“I will not talk about race, I will not talk about gender- without talking about them both. I’ve lived them both.”

—Anita Hill

Although Hill’s testimony sparked this conversation 27 years ago, only recently has the conversation sparked a movement.

In 1992, there were almost 10 times as many sexual harassment claims filed with the EEOC than the year before — from 1,244 to 10,532. This is a source of pride for Hill.

“I’m not just proud of the fact that they filed complaints in court or with their employers; I’m also proud that they were able to share their stories with their families,” she said. ”This is something that women had been keeping secret from the people who cared about them…and just had no idea that they had to suffer.”

Hill has had many accomplishments beyond her difficult testimony from that year.

She became the first tenured Black professor at the University of Oklahoma, wrote several books, and has remained an advocate for equality for over the last 27 years.

She’s now a full-time law professor at Brandeis University, although she is currently on a one-year leave.

And her leave is not a vacation — she’s at MIT assessing the 45th year of Title IX and researching the various ways that women still suffer disadvantages in higher education, particularly women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math).

She’s also serving on the board of directors of the National Women’s Law Center, the organization that administers the money raised from the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund.

When I asked Hill what her greatest accomplishment was, she said, “I haven’t had it yet.”

Hill is proud “that the groundwork that had been laid by me and by many other women who have been involved in research, filed complaints, or done advocacy work has led to this moment.”

But she says there is still work to do.

“With the work of this commission, and with the work that I’m continuing to do, I’m [confident] that we will see more change,” she said.

Women’s movements are working to hold abusers accountable, and reduce the risks of coming forward with sexual harassment complaints. But Hill said it’s still not possible for every woman to formally come forward.

“Not everybody’s going to be able to file a complaint, because we still know that there are women who are too vulnerable to come forward,” she said.

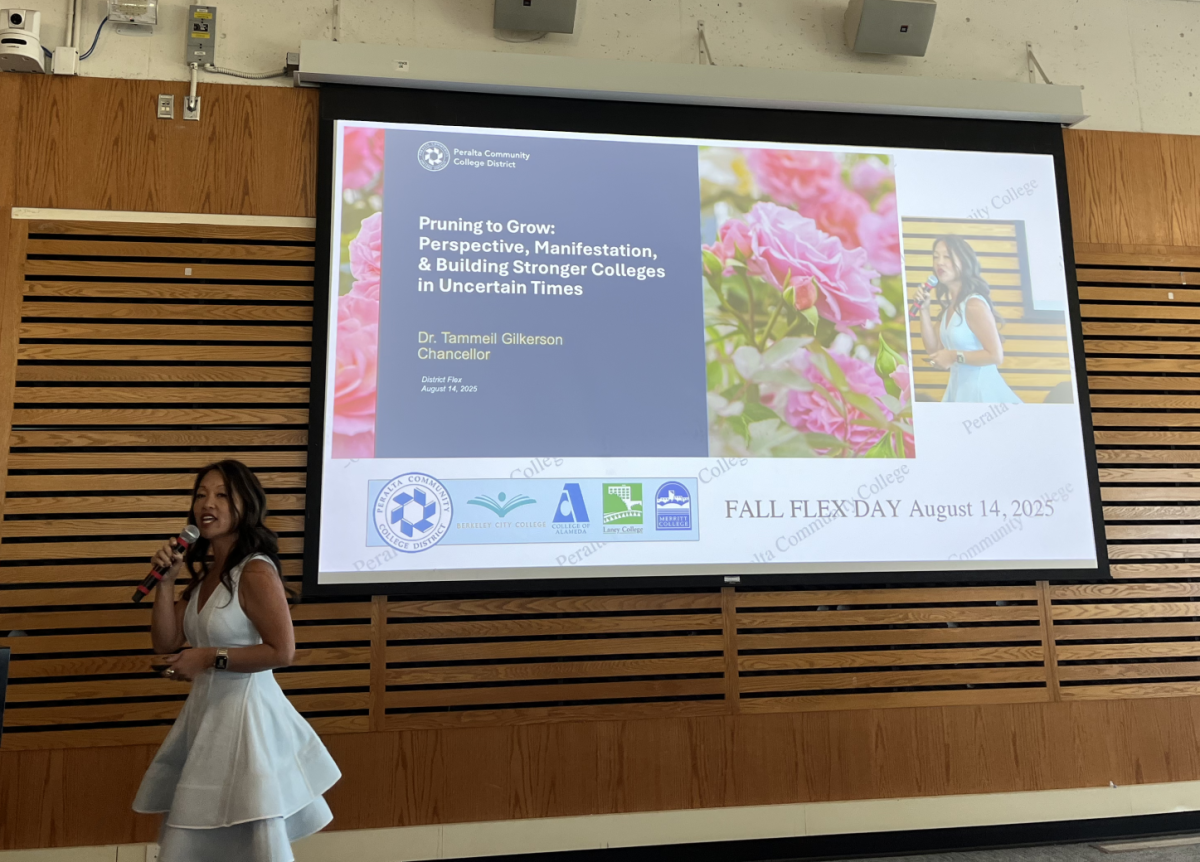

About 2,000 people filled the Oakland Marriott Ballroom to watch Anita Hill speak at the Barbara Lee & Elihu Harris Lecture Series on Saturday, March 10.

The series, in partnership with the Peralta Colleges and the Martin Luther King, Jr., Freedom Center, invited Hill to speak during Women’s History Month on the topic of gender equality.

Hill discussed gender and racial violence, and said that both are committed in search of power.

“I will not talk about race, I will not talk about gender — without talking about them both. I’ve lived them both,” she said, “and I would say to every one of you — you live them both, too.”

She explained how Justice Thomas’ description of her testimony as a “high-tech lynching” solidified his lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court. She said his choice of language made an all-white-male judiciary committee fearful of being called racists.

Thomas was nominated by President George H.W. Bush to replace Thurgood Marshall, who was also Black.

“He wanted to name an African American to take the place of Thurgood Marshall,” Hill said. But she said Thomas could only replace Marshall as a body, not ideologically. “The contrast between Judge Thomas and Justice Marshall was individualism versus community — it was clear.”

Since 1991, the nation has become more prepared to deal with complaints of sexual harassment. The Violence Against Women Act was passed by Congress in 1994, making it the first comprehensive federal legislation package designed to end violence against women.

Hill cited stories of women coming forward with complaints earlier than 1991, claiming that she along with women today who are part of the #MeToo movement are standing on the shoulders of these women, for whom it was even more difficult to make their case.

“There may have been a time when we had to excuse and assume that sexual predation was just something men did,” she said. “But that day has passed.”

The crowd erupted in cheers.

“And for those who say that things are no different than in 1991 — I say you’re wrong,” she said. “Because in 1991, there would not be a hall full of people applauding that line.”

Oakland resident Xiao Wen Chen attended the lecture with two of her friends. “I was very inspired,” she said. “Women should not give up their civil rights.” Chen said the speech made her feel more motivated to stand up for herself in the face of sexual harassment. “We have the right to protect ourselves.”

Catherine Addison, also of Oakland, said that Hill’s calls for courage to stop gender violence, while not new, were still needed. “Just to hear a pioneer like her come out and say those things again was uplifting,” she said.

Sarah Carpenter co-editor-in-chief of the Laney Tower.