College outreach group supports students who have been imprisoned

by Meg Duff

More than most people, Vincent Garrett understands the importance of peer mentoring. About a decade after he was released from prison, Garrett signed up for classes at Merritt College. That’s where he met his mentor, Ron Moss.

Moss showed Garrett the ropes. Moss went on to transfer to UC Berkeley, graduating in 2015. Garrett followed in his footsteps and graduated from Cal a year later.

Now, both men are helping other students in the Peralta district succeed. After earning a masters in social welfare, Moss is back at Merritt College running Street Scholars, a program he founded in 2014 for formerly incarcerated and system-impacted students.

Garrett, who is also working towards a master’s degree, is now the program outreach and retention specialist for Restoring Our Communities (ROC), a similar program at Laney College.

Founded in 2016, ROC provides both material support and peer mentoring to formerly incarcerated and justice system-impacted students. The majority of ROC staff and advocates are themselves formerly incarcerated. As peer role models, they can provide unique support.

“Peer mentoring is all about social capital,” says Garrett. “Often, people come to ROC because we can offer material resources, like food vouchers. But when they come in, we check in. Mentors who were able to transfer and go on to the next level can share that information and be role models.”

For formerly incarcerated and system-impacted students, peer mentors can uniquely relate to the challenges of navigating two complex bureaucracies: the justice system and higher education.

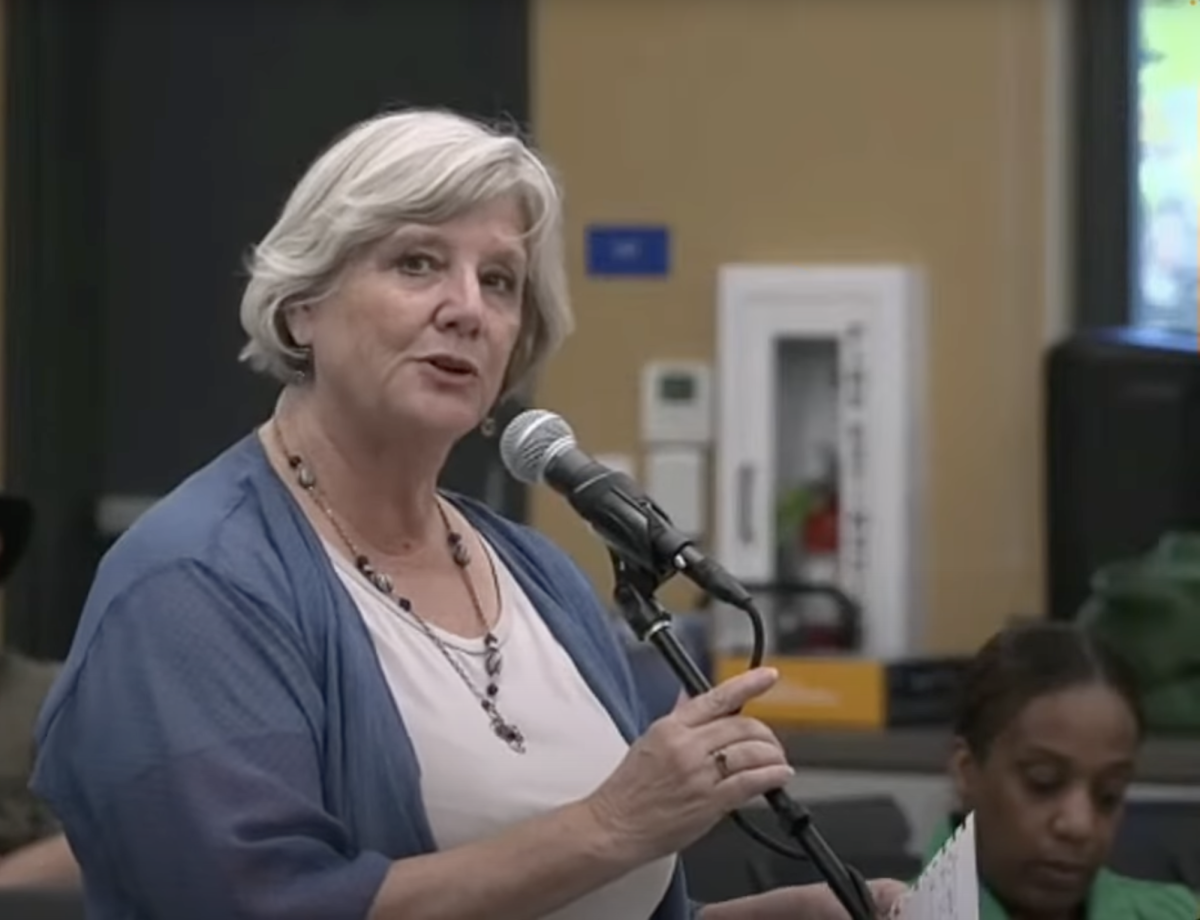

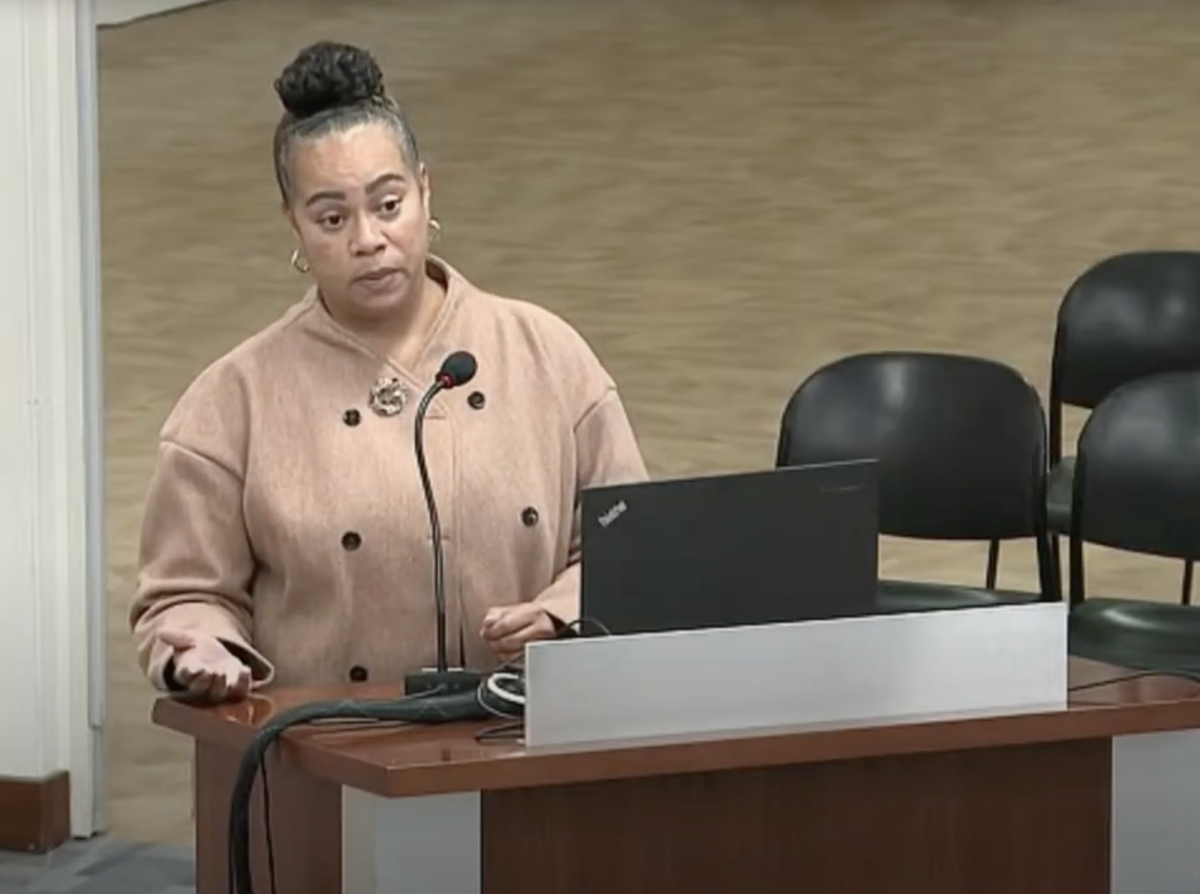

“One Laney student this semester had a parole hearing and exam scheduled for the same day,” says Alejandra Landin, equity specialist for the ROC. “These students have to make hard choices. Do you risk failing a class, or do you risk more prison time?”

(Photo by Brian Howey)

ROC staff can help students to bridge those bureaucracies, for example, by writing letters of support to let probation officers know that students are participating on campus. They can also connect students to other resources for support. “We support each other to create doors and walk through them where none existed,” said Landin.

Students can drop by the ROC office in E203 anytime between 9 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. Monday through Thursday. Staff and ambassadors offer one-on-one tutoring, help students navigate financial aid options, and even give rides to parole hearings.

The center has already impacted students here. Last year, 92 students received material support from ROC in the form of food vouchers, BART cards, money for textbooks, and more. Many more came by E203 to use computers or space and to talk with ambassadors and staff.

Program director Roger Chung, a professor in the Ethnic Studies Department, estimates that almost 200 students have taken advantage of the program so far. About 50 percent are women, even though women are less represented in the justice system as a whole.

Although California community colleges do not track enrollment or outcomes for formerly incarcerated or system impacted students, a fall 2017 assessment showed that students who connect with ROC are succeeding in their classes at the same rate as other Laney students.

Chung founded ROC in 2016 in response to a grant by the California Community Colleges System Chancellor’s Office grant to support innovative programs. After the first semester, the program has been funded by Laney’s student equity budget. Currently, ROC receives in-kind space from Laney College and funding to pay Landin and Garrett for 20 hours of work per week.

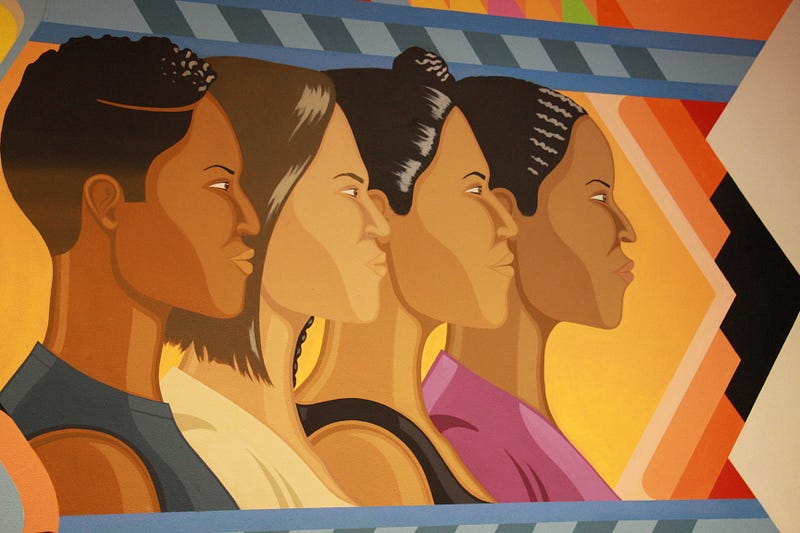

The ROC office is welcoming. Students are greeted by comfortable couches, computer stations, and a large, colorful LGBTQ “safe space” mural painted by local artist Oree Originol. Garrett pointed out that touches like the mural matter; they tell students about the values and priorities of the space they are in.

Students can help create a welcoming community. Instead of saying “felon” or “convict” Pierini recommends “formerly incarcerated.”

“It’s eerie — in my program, I’ll read recommendations that schools do things like put up murals, and I then I see these things at ROC. We are already doing them,” says Garrett, who is working towards a masters in organization and leadership at University of San Francisco.

Now that the center is becoming better known, the ROC staff are focusing in on deepening support for the students currently involved. “We are drilling down on the best practices for student success,” says Chung. “We support students with matriculation, financial aid, and enrolling in other programs. We also work with community partners to connect students with jobs and work with the public defender to dismiss records.”

According to the California Department of Corrections, 183,000 people across California are currently incarcerated or on parole. More than 400,000 are formerly incarcerated, and many more have been impacted by the system through family members. The Degrees of Freedom report by UC Berkeley Law suggests that the kind of open-access, peer support that ROC provides can help formerly incarcerated students realize their higher education goals.

Finessing the Game (FtG), a new student group founded this fall in collaboration with the Berkeley Underground Scholars program, promotes awareness of ROC through outreach activities. Phil Pierini, a student at both Laney and UC Berkeley, founded FtG this fall. The group meets on the first Tuesday of every month at noon in E203.

Pierini and Landin emphasize that the entire Laney community can help formerly incarcerated and system-impacted students succeed. Professors can be flexible when possible, knowing that formerly incarcerated and system-impacted students must navigate two complex bureaucracies, often with competing demands.

Faculty can also invite ROC ambassadors to speak in their classes and can connect individual students to the program; some faculty and staff are already doing both. “Now, counselors and professors are coming to us to let us know about students they think would benefit from involvement,” said Landin.

Initiatives that help under-resourced students can also benefit formerly incarcerated students. The Ella Baker Center found that three in five formerly incarcerated students in one survey were unable to afford to return to school. “Sometimes, the choice can be to buy the textbook that the professor wrote or to pay utilities that month,” said Landin. Many students who take advantage of ROC resources are eligible for other supports as well.

Even though students may not know which of their classmates are formerly incarcerated or system-impacted, they can help create a welcoming community. Instead of saying “felon” or “convict” Pierini recommends that students use the phrase “formerly incarcerated,” which carries less stigma.

Pierini hopes that students will also question stereotypes they may have heard.

“Most people have moved forward and taken steps to grow, heal, and put the past behind them,” he says.

Meg Duff is a Laney Tower staff writer.