A century-long history of homelessness in Alameda County puts economic inequity at the heart of modern displacement

by Alice Feller

PIPE CITY

In September 1930, an impromptu city sprang up at the foot of 19th Avenue in Oakland, where 200 homeless men found shelter in lengths of unused concrete sewer pipe. The men called their town “Misery City,” but to the rest of the world it was “Pipe City.”

The “mayor” of Pipe City was Dutch Jensen, an out-of-work construction crew boss. He ran the town on three simple rules: “No drinking, no slovenliness, no talking politics.”

To become a citizen, you needed to be jobless and homeless, but definitely not helpless. No begging was tolerated, no government assistance allowed.

Jensen negotiated with the American Concrete and Steel Pipe Company f or the rights to camp out in the company’s surplus pipe. He organized the community into sections and sent the residents out each day to forage for food. The day’s harvest was made into a communal dinner each night.

Any leftovers were kept in a tightly guarded storeroom — Frank Sewell was appointed “police chief.”

Both Oakland and San Francisco created public works projects to help bolster employment. The largest of these projects was the construction of the Bay Bridge, which began in 1933 and created more than 800 jobs for unemployed construction workers.

Pipe City was voluntarily closed by the residents in the spring of 1933. Upon leaving, they cleaned up behind themselves and returned the area to its original condition.

HOMELESSNESS IN 2016

Homelessness as we know it today is a new phenomenon. Until recently Americans did not live on the streets. Episodes of homelessness occurred during economic cataclysms, such as the crash of 1873 and the Great Depression. But when those hard times ended, the unemployed found work and shelter.

Policies initiated in the 1960’s and 1970’s produced major changes that created a new brand of homelessness — a deeply marginalized population which lives on the streets even in times of general prosperity.

PANHANDLING TO LIVE

Kyle sits on Telegraph Avenue with a cardboard sign that reads, “Just need weed.” He looks up from the sidewalk, flashes a winning smile, and says, “But money will do.”

Kyle has been living on the streets for 20 years, ever since he turned 18 and left his foster family. As far as he knows, his own family is still in Arizona, but he lost track of them long ago.

A cold wind blows off the Bay; Kyle is wrapped in a pale yellow blanket smudged with dirt. Under that, he wears an oversize army surplus jacket with the hood up. Only his hands and face are exposed to the frigid air.

He is missing all his lower teeth on one side, as if at some point he took a calamitous punch in the mouth. His fingers bear crude tattoos and the ground-in dirt covers him like an extra layer of skin.

Kyle can’t remember the year he should have graduated from high school, or even which decade he attended high school. No one was paying much attention to his schoolwork, not his teachers, not his foster parents, not Kyle himself.

When he turned 18, he aged out of foster care and suddenly was on his own without a job. Asked how he’s supported himself these past 20 years, he nods at the upturned hat on the sidewalk in front of him. Currently, it holds one quarter.

MANUFACTURING JOBS

Not so long ago it would have been easy for an unskilled worker like Kyle to find a job to supply his basic needs, but things have changed.

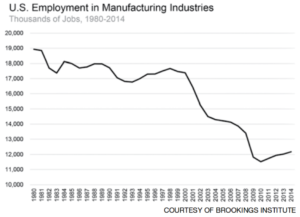

Since 1980, nearly seven million manufacturing jobs were lost to globalization, off-shoring and automation. These were good jobs with benefits. Workers laid off usually ended up with temporary or part-time work, if they found work at all. More than five million households fell into poverty.

And yet, ironically, the unemployment figures have been relatively reassuring. The Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys households (automatically leaving out anyone living on the streets) and tallies those working and those looking for work.

Any sort of job, no matter how minimal, counts as employment. Those who have given up looking for work are not counted. Consequently, the tectonic shift of industrial jobs away from the U.S. never registered as a rise in unemployment, which as of today stands officially at 4.7 percent.

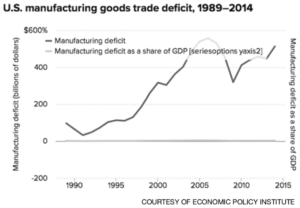

Robert E. Scott of the Economic Policy Institute writes that while NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) and KORUS (U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement) together took away almost one million manufacturing jobs, the trade agreement with China eliminated 3.2 million jobs.

President Bill Clinton had assured the public that China’s entry into the WTO would create a “win-win” situation.

Vast numbers of American jobs would be created “with the new access to the Chinese market.”

Instead, a precipitous job loss (see figure above) and a steep rise in the trade deficit (see figure left) resulted from this new trade pact.

Currency manipulation by foreign countries has further aggravated the balance of trade and contributed to job loss. By depressing the value of its own currency, the intervening country makes its exports cost less and the target country’s exports cost more.

Thus, through currency manipulation alone the intervening country gains an advantage in trade and puts the target country at a disadvantage. The U.S. has been targeted most egregiously by China, Denmark, Hong Kong, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Switzerland and Taiwan (in rank order).

LOWER-INCOME HOUSING

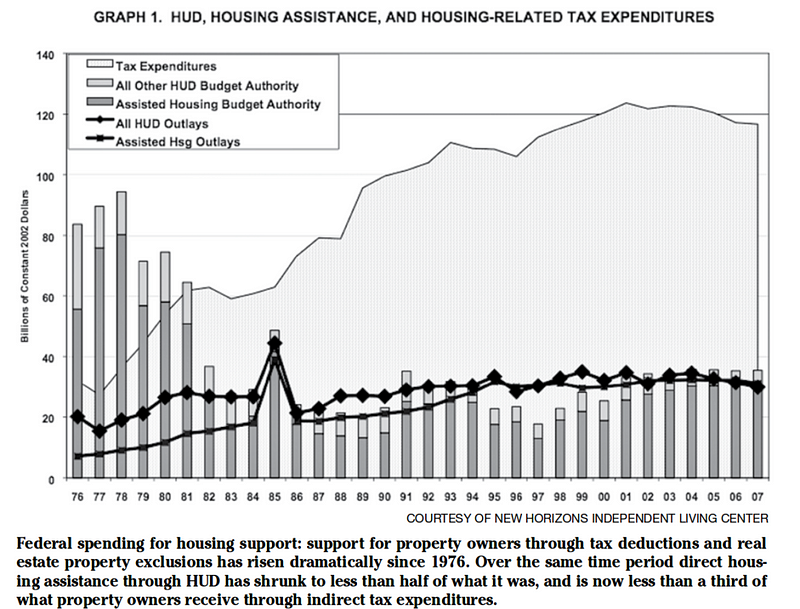

Over the same time period that eight million factory jobs were liquidated and five million households fell into poverty, one million units of low-cost housing were lost due to changes in public policy.

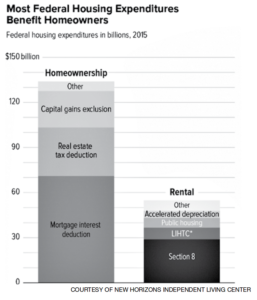

Urban renewal, with generous funding through HUD, destroyed much of the last housing available to the poor. Up until 1974, federal programs such as Section 8 housing had given direct assistance to low-income households.

Then, President Gerald Ford signed into law the 1974 Housing and Community Development Act and everything changed. Funds were given as block grants to the states on a competitive basis, to be administered as the localities saw fit.

The figures above and to the right show what happened. Urban renewal was the new priority for HUD funding and the bulk of all federal money for housing ended up in the pockets of property owners, largely through tax advantages.

URBAN RENEWAL

The city of Oakland provides a good example of urban renewal. In 1999, when Jerry Brown was elected Mayor of Oakland, the city had been losing its population.

Brown promised to bring 10,000 new residents to the city — his famous “10K plan.” He aimed to remove the 24 residential hotels in downtown Oakland and replace them with market rate and affordable housing,

Terry Messman, writing for Street Spirit newspaper, called Brown’s plan a Trojan Horse. “The hidden part of this so-called ‘10K’ plan,” he wrote, “is to drive away all the social problems and poor people that might make downtown Oakland an unappealing place to live for your average, upwardly mobile dot-commer.”

Fifteen years later, the Sutter Hotel, one of the last remaining SRO’s (Single Room Occupancy) in downtown Oakland, is about to be sold to developers.

The East Bay Express reports that the new owners will convert the building into another boutique hotel or possibly a hostel for tourists.

Dion Ross, who describes himself as a “project implementation strategist,” recently took Stephan Yang of Yang Capital on a tour of the 102-room hotel. Ross was hired by Sutter Hotel owner Raj Singh to show the building to interested investors without attracting too much attention.

Another downtown SRO is the Hotel Travelers. Investor Danny Haber plans to rent out the rooms to tourists at more than double their current rate. The refurbished building will feature a rooftop beer garden.

HOMELESS IN BERKELEY

Kyle is enthusiastic about the accommodations in Berkeley. “Every Saturday morning they feed all the people in the park so I usually hang out and get tons of food,” he says. Although he claims that he eats all the time Kyle is bone-thin.

He has no idea where he will sleep tonight. “I usually pick random spots — makes it safer. Like, this is ‘chill’ you know, and I just go there.”

He avoids the homeless shelters because “you get most of the crazies there — it always smells like feet — and I wake up with my stuff stolen.”

“It’s a scientifically proven fact,” he says, “that anyone on the street has post-traumatic stress. And anyone who doesn’t have it should be considered not right in the head. But I know how to roll with it.”

Entitlement programs such as AFDC and Section 8 Housing are a vital safety net to help keep the vulnerable from falling into the despair of homelessness.

A pair of young women in distressed blue jeans and soft leather boots appear at this point, offering clean needles and condoms. Kyle waves them away.

This seems like a good sign. As his sign says: “Just need weed.”

But then his speech begins to slur. His sentences stop making sense.

He has trouble keeping his head up and it becomes clear that he’s nodding out. It seems that what Kyle is struggling with will need a much better, more permanent solution.

SOCIAL SAFETY NET: LOST

In 1996 Clinton signed into law what was billed as welfare reform. Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was replaced by block grants to the states to be distributed as they saw fit, with no guarantees of even minimal support for children and families in poverty.

The philosophy behind welfare reform was that welfare was bad for recipients because it fostered dependence. These beliefs were fueled by a deep anger among voters who imagined they were being taken for a ride by Cadillac-driving “welfare queens.”

Under the new law families slipped into deeper poverty, often losing their homes in the process.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

The state mental hospitals began closing down nationwide in the Sixties, earlier in California. By 1994 nearly half a million patients had been discharged.

This movement, known as “deinstitutionalization,” came about through a political alliance of the far right and far left. On the radical left, it was fashionable in some circles to argue that there was no such thing as mental illness, that what looked like insanity was actually the sane response to an insane society.

Those who had more knowledge of mental illness hoped that the newly developed antipsychotic drugs such as Thorazine would enable the former mental patients to function normally outside the hospital.

“It’s a scientifically proven fact that anyone on the street has post-traumatic stress. And anyone who doesn’t have it should be considered not right in the head.”

And the so-called Mental Health Bar treated the issue as one of civil rights, with the goal being liberation of the “inmates.” These lawyers didn’t stay in touch with their clients after they left the hospitals. Nor were they moved to liberate them when they became inmates once again, this time in the prison system.

On the political right were fiscal conservatives whose goal was to save money. Shutting down the state hospitals saved vast sums.

Theoretically, these funds would go toward community mental health. But few of the taxpayers on the right or the left followed up on this plan and community mental health foundered for lack of funding.

Patients were discharged to nursing homes or to the care of their families, neither of which were equipped to handle them. As many as half of all former state hospital patients became homeless within months after leaving the hospital and many others ended up in jail.

E. Fuller Torrey writes, “In 1955 there was one psychiatric bed for every 300 Americans. By 2005 there was one psychiatric bed for every 3,000 Americans.

“Even worse,” he adds, “the majority of the existing beds were filled with court-ordered (forensic) cases and thus not really available.”

The reason for this difficulty is the IMD (Institutions for Mental Diseases) exclusion, also known as the “16-bed rule.” This little-known coda was added in 1965 when Congress amended the Social Security Act to create Medicaid.

The IMD exclusion forbids the use of Medicaid to pay for patient care in “institutions for mental diseases” (IMD’s), defined as any hospital or residential facility with 16 or more beds and doctors on staff with psychiatric training.

This rule puts the financial burden of psychiatric hospital care entirely on the state, unlike any other kind of hospital care, much of which is paid for by the federal government through Medicaid (MediCal in California).

The IMD exclusion accounts for the scarcity of psychiatric beds at the community level and for the lack of residential substance abuse treatment facilities for adults.

Theoretically, the mentally ill homeless person can get a MediCal card and make use of opportunities for outpatient psychiatric care and substance abuse treatment.

But even the high-functioning and stably housed person often has difficulty navigating today’s mental health system and getting outpatient care through MediCal.

As a practical matter, a person suffering both from mental illness and unstable housing can find this task impossible; in the worst cases, the solution can end up being self-medication with alcohol and street drugs.

Torrey writes that we have come full circle from the beginning of the 20th century, when Dorothea Dix campaigned to rescue the insane from prisons where they languished, often under inhumane conditions. Due to her work, the mentally ill were rescued from prisons to be cared for in hospitals.

But now that the state hospitals have closed down, the prisons once again house most of those suffering from severe mental illness. Prisons are now our largest providers of mental health care.

Just as prisons have become the de facto providers of institutional mental health care, the police are now the first-line providers of mental health care on the streets.

Officer Jeff Shannon of the Berkeley Police Department estimates that nationwide 20 percent of service calls are for mental health crises while that figure is more like 30 percent in Berkeley, nearly all for homeless people with mental illness.

“This is a voter issue. If the community doesn’t want people languishing in jail with mental illness, fund the mental health system so that we can do our job.”

Shannon runs the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training program for his fellow officers in Berkeley and Oakland. CIT involves learning about mental illness and the use of de-escalation techniques to cool down a situation before it gets out of control.

“We’ve become the mental health first line of defense,” he says. “And a lot of officers resent that.” Nevertheless, Shannon says, they do an admirable job in a role they never signed up for.

Like Torrey, he laments the lack of psychiatric hospital beds. Alameda County has one psychiatric hospital, the John George Psychiatric Hospital. But the county has a high number of 5150’s — individuals placed on 72-hour involuntary hold — and about 80 admissions a day for only 69 beds.

“They’re overwhelmed,” Shannon says. “There’s always pressure to release people. You have a glass that holds eight ounces of water and you take a pitcher and pour 16 ounces of water into it. That’s what we’re looking at.

“I think the mental health system has been more or less destroyed over the last 50 years as a result of deinstitutionalization.

“We have 10 percent of the hospital beds that we had back then,” he says. “The funding never came through so you have these people that are very sick and they end up in jail.

“This is a voter issue. If the community doesn’t want people languishing in jail with mental illness, fund the mental health system so that we can do our job.”

THE SOLUTIONS

Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment

Mental illness and substance abuse need to be recognized as treatable conditions rather than permanent disabilities. The community mental health system should be funded as originally intended.

The IMD exclusion should be discontinued so that people who need residential substance abuse treatment and psychiatric care can be treated appropriately. Residential treatment is especially important for the homeless.

Public Works Projects

Scott of the Economic Policy Institute suggests that we rebuild our crumbling infrastructure. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, we will need to invest $3.6 trillion by 2020 in order to rebuild our aging roads, ports, airports and other public facilities.

This massive public works project, Scott writes, “would create up to three million new jobs and boost the gross domestic product by $400 billion through debt-financed investments of an additional $250 billion per year in infrastructure for the next seven years.”

Address Currency Manipulation

The EPI estimates that action to address currency manipulation could reduce the trade deficit by $200 to $500 billion and create 2.3 to 5.8 million new jobs, 40 percent of which would be in manufacturing.

C. Fred Bergsten and Joseph E. Gagnon of the Peterson Institute for International Economics offer four possible approaches including bringing a case against the currency manipulators in the WTO and currency intervention to end the effects of the intervening countries’ actions.

Rethink Future Trade Agreements

Scott writes, “Most workers would be hurt if trade with low-wage countries were increased by the TPP; most of the benefits would go to those at the top of the income distribution.”

It will be corporations that benefit, he argues, who have “few if any organic ties to the U.S. economy — most have outsourced a large share of production jobs to other countries.”

The greatest beneficiaries, he says, will be those who own stock in these corporations. And the more stock you own, the more you stand to benefit. He concludes that the TPP “will only serve to worsen U.S. income inequality.”

Restore Welfare and Housing Assistance:

The block grant system should be ended, while restoring guaranteed assistance for the poorest of our citizens. Entitlement programs such as AFDC and Section 8 Housing are a vital safety net to help keep the vulnerable from falling into the despair of homelessness.

Alice Feller is the Assignments Editor for the Laney Tower. Contact her at [email protected].