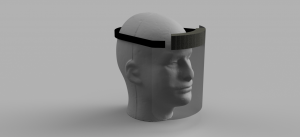

Plans to develop face shields are underway at two Peralta colleges to help buffer the growing threat of dwindling supplies as COVID-19 spreads. Facilitators will utilize local and campus machinery workshops to prototype, produce, and distribute the personal protective equipment (PPE) to local hospitals in need of supplies.

“Digital fabrication is all about producing things as fast as possible,” said Rick Rothbart, lead technician of the Laney College Digital Fabrication Lab (FabLab).

“I can’t think of any more of an appropriate time in history for people with these kinds of skills to come together and create something life saving in as short amount of time as possible.”

These measures are part of a larger movement happening in vastly different sectors of manufacturing, from Tesla’s offer to manufacture ventilators to Gap’s offer to produce surgical gowns and masks.

“There is a large number of people actively out there doing this kind of stuff. Some of it is centrally coordinated, but much of it is smaller, individual groups [who] decided to do this on their own,” said Danny Beesley, a contractor affiliated with the Peralta FabLabs.

At the FabLabs of Laney College and College of Alameda, students and community members are invited to learn how to operate and use advanced manufacturing equipment and the software that accompanies it. Laser cutters, 3D printers, CNC routers, and embroidery machines are all equipment that can be found in the Peralta FabLabs. They are part of a global network of FabLabs known for education and innovation, and typically serve the campuses as walk-in resource centers.

In late March, Rick Rothbart and Levi Williams of Laney College, Vince Stevenson of College of Alameda, and Mark Martin, who works with Laney as a regional director of advanced manufacturing, focused on perfecting a prototype for a face shield at Laney’s FabLab. Face shields are made of a wrap-around clear plastic barrier meant to protect wearers from airborne particles. They are currently in high demand from hospitals as they are used to protect health care workers from exposure to COVID-19.

“The beauty about the FabLab is that you can take digital designs and rapidly prototype them,” Martin said.

Rothbart said the team tweaked an existing design, provided by a Wisconsin design firm called Delve, to accomodate adjustable straps. Next, he said, the prototype was critiqued by doctors and refined based on their feedback.

“We don’t want to create something that we think they’ll use, but we want to make sure that what we’re creating is something that they want to actually use,” Rothbart said.

After viewing the prototype, Highland Hospital in Oakland has requested 10,000 of the face shields, dubbed the LaneyShield LS-01 design by the Peralta team.

The first 500 were assembled and completed within the first week of April at Oakland’s Port Workspaces, according to the Laney FabLab Instagram account. Martin plans to sell the face shields for the cost of producing them to Highland Hospital and other hospitals that request PPE. The team is only interested in covering material and labor costs. Each mask, Marin reported, costs about five dollars to produce.

While the team would have liked to mass produce face shields at the Peralta college FabLabs, they faced barriers in the form of limited production capabilities and raw material shortages. First, the team has limited access and significant time constraints, because campuses are only open to staff for essential purposes for eight hours a week during shelter-in-place orders.

“Most of the machines that we have are not quite the industrial scale needed for doing mass production,” Beesley said. If they were to produce at the campus FabLabs, they would have to use laser cutters to manufacture the shields, which don’t operate as quickly. So the team looked for other production venues.

“It would be pretty hard to keep up with any demand that a hospital would need,” Rothbart explained. “So that’s why we’re turning towards local partnerships with other companies that can do this for us.”

So far, one fruitful partnership has been with Oakland-based Automatic Arts, which has die cutters, a machine that can stamp out dozens of shield parts per minute. According to their website, Automatic Arts has the capacity to develop 2000-4000 faceshields per day, depending on the type.

But a second, and even bigger obstacle than paying for the materials seems to be sourcing them. Martin said they’ve been paying for materials for the shields out-of-pocket so far. When the team tried to order materials from McMaster, a supply company that usually ships overnight, they learned that materials could take up to three weeks to arrive.

“We started looking for the materials elsewhere and discovered that there was a nationwide shortage of the stuff,” Martin said. “Everybody’s trying to get this thin plastic material and the foam itself.”

For the first 500 shields, the team was able to get enough small orders of material to start producing last week. For the next batch, Martin said it’s a matter of “just digging a little deeper” to get contacts and folks who can supply materials. As the project continues, Beesley said that materials might be donated from some Alameda manufacturers with excess product or from national plastic suppliers.

Theoretically, Martin estimated that the order of 10,000 face shields could be completed in a

number of days. But because of the importance of social distancing, the limited work space, and the delay between getting materials and producing the product, it’s going to take a bit longer. An exact timeline, at this point, is unknown.

In addition to producing the masks, Rothbart said that the design for the LaneyShield LS-01 will be posted online for free public access.

Students will have the opportunity to be involved as well. Beesley said that they’ve reached out to Peralta Apparel Design and Manufacturing students to see if they are willing and able to sew surgical masks and gowns from home.

Martin also emphasized the learning opportunities coming to light with the project. “[It’s an] example of what can be done in a FabLab and how it can contribute to the community, but also the learning and skill sets of our students.”

The work happening at the Laney and College of Alameda FabLabs is one crucial piece in a very large effort.

“A good friend of mine has been adopted essentially to help lead a large scale distributed manufacturing PPE production project,” Beesley explained. “and so I’m helping him get that established and set up and put in the infrastructure so that that can scale very quickly.”

“Because the FabLabs exist, because [of] the kind of community nature of the FabLabs, all of this is possible in the first place,” Beesley said.

An update to this story can be read here.