Energized by the wave of national protests against police brutality, faculty and students at Peralta Community College District have adopted an active role in conversations about safety and law enforcement reform. The administration and board of trustees — who debated this issue and sought potential new security models last year — are welcoming community participation.

At the district, a hybrid model of security that would rely less heavily on traditional law enforcement on campuses was proposed at the June 9 board of trustees meeting.

Yet many faculty and students are insisting on deeper reform, unsatisfied with the proposal to reduce police presence on campuses rather than eliminate them entirely. Eight speakers appeared at the June 9 meeting to urge the board to end Peralta’s contract with Alameda County Sheriff’s Office (ACSO). Their demands are accompanied by similar pleas emerging from schools across the nation, including Oakland Unified School District.

On June 8, a group composed of faculty, staff, and students called #BlackMindsMatter at Peralta circulated a petition demanding that the board of trustees terminate the district’s 4.1 million dollar contract with ACSO. As of June 22, the petition had 1,357 signatures. Supporters of the petition want to relocate funds to immediately invest in Black and Brown students. The current contract with ACSO is set to expire on June 30, and the board of trustees is scheduled to vote on its renewal during their June 23 meeting.

Concerns with ACSO

An early sentence in the petition reads: “Black and Brown youth are under attack,” citing racial profiling as the primary reason to terminate Peralta’s contract with ACSO.

ACSO Public Information Officer Sergeant Ray Kelly said that ACSO officers participate in anti-bias and cultural sensitivity training “on a regular basis.”

“We’re constantly training and lecturing and learning around those topics,” he said.

Laney Department Chair of Ethnic Studies Roger Chung signed the petition. Chung is the director of Restoring Our Communities, an organization that helps students who were formerly incarcerated navigate college. He explained that he is not necessarily concerned about the specific officers who are stationed at Peralta, but about the system itself.

Some formerly-incarcerated students at Laney are now on probation or parole, and are therefore “heavily dissuaded” from making formal contact with law enforcement, Chung said, since documented contact with police might result in a violation of parole or probation, enhanced supervision, or jail time. Students who were formerly incarcerated “have to weigh the costs and the benefits of dealing with the repercussions of having contact with law enforcement,” he said.

“Whether or not the officers themselves are kind, whether or not they have strong diversity training and bias training — just having a law enforcement as the entity already, to some degree, guarantees a system of segregated safety,” Chung said. “Because we’re looking at some individuals [who] feel like they can use a sheriff for their own safety, and other individuals not being able to use the sheriff for their safety.”

Kelly disagreed and said that when interacting with students who were formerly incarcerated, it “would not benefit our communities to re-incarcerate them, nor do we want to, especially for some type of petty offense.”

“Any time we can get a returning student who was formerly incarcerated back at school and on campus and learning, I think that’s great. I think that’s awesome,” Kelly said.

Chung said that another problem with having traditional law enforcement on college campuses is that those accused of crime must undergo two disciplinary systems – one through the school, and one through the county’s criminal justice system. Furthermore, police officers, who have access to everyone’s criminal history, might subconsciously reprimand students who were formerly incarcerated to a harsher degree than students who were not, Chung said. He would rather see a process where “we’re doing something internal, we’re moving it through the college’s disciplinary process, and then if it has to go to criminal court, then it can go to criminal court.”

Birth of the petition and its demands

Plans for the petition blossomed from a conversation about the “urgency and consistency” of the Black Lives Matter movement, according to Laney Professor and Peralta Federation of Teachers Vice President Kimberly King, a primary organizer in the effort to abolish Peralta’s ties with ACSO.

The state Chancellor’s office and Peralta district held town halls in early June about developing solutions in an educational setting, which largely concluded that unconscious bias and cultural diversity training is the remedy, King said. She and others felt inspired to brainstorm larger-scale options. The town halls “didn’t really mention at all the things we really could do: actions, actual material differences in students’ lives that they would not have to see the police that they’re traumatized by,” King said.

“I’m not saying that [education] is not a part of the solution, but I was just so struck at how small of a solution that was compared to the problem,” King said. Noting that the Minneapolis police department went through anti-bias training, King said that there must be more active options out there.

The petition lists four primary demands: end the contract with ACSO, implement “community-minded campus safety measures,” protest approaching budget cuts from the state, and prioritize funding to “ensure student safety and real opportunities to make #BlackMindsMatter.”

Supporters want funding to be diverted from the security contract and go toward providing students with basic needs, including health resources, housing, food, and technology and internet access, among other things.

With hundreds of millions of dollars in proposed budget cuts looming over California Community Colleges, King said she’d like to see the Peralta administration mobilize in protest — in the form of email or letter-writing campaigns, lobbying, or virtual demonstrations — to help pay for the above-listed equity-aimed resources.

“The chancellor and the board of trustees, they have a way to contact thousands of people who are part of this district, so they have a way to mobilize citizens and community members to put pressure on our government,” King said.

Peralta Community College District Chancellor Regina Stanback Stroud wrote in an email to The Citizen that although some demands in the petition “are not related to the model of safety and security,” the district does participate in efforts to “advocate for a budget that will support the mission of the community colleges.” Those efforts include talking to the legislature about the impact of budget proposals, writing letters, and participating in advocacy groups.

The petition has reached students as well. Associated Students of Laney College President Alycia Raya said she’s been serving as a liaison between the petition’s writers and the student body. It’s “an opportunity for students, non-Black allies and non-Black people of color to just immediately be an ally [by] just signing petitions, signing in solidarity [of] these demands,” she said.

Raya sent a mass email to Laney students on June 18 encouraging them to sign the petition and register to speak during public comment at the June 23 board of trustees meeting.

“These trustees are elected by us. They quite literally work for us. We are not only the students that they swear to serve and provide for and protect, but also we’re their voting constituents. So we quite literally have power,” Raya said.

“And if we genuinely come together and demand they defund the police, they will.”

Skepticism

The petition does not suggest specific alternatives to ACSO.

“A lot of folks are kind of feeling that because the sheriff has been such an institutional presence that if we don’t have the sheriff, we don’t have anything,” Chung said.

King emphasized that understanding the meaning of “defunding” is key to understanding the petitioners’ intentions. The goal is to reduce spending on law enforcement presence where it’s shown to be utilized less. Savings can then be directed toward supporting students.

“We’re not proposing that there not be any type of public safety on campus — because, yeah, people need to feel safe on campus — we want everyone to feel safe, though, not just certain people,” King said.

Terrance Greene, a Laney faculty member and counselor, has not signed the petition. Greene said his hesitance is partly due to previous break-ins and assaults at Laney’s campus, but also because plans for alternative security systems are unclear. Further, he hesitates to put students in difficult situations serving as security aides or security personnel without traditional officer training.

Sergeant Kelly said that such alternatives are not comparable to traditional law enforcement. “I think when it comes to an emergency type of situation, the difference between a security guard and a trained police officer is a big difference,” he said.

“I know that it may be popular or it may be trendy to vote out law enforcement out of your district. But at the same time, I think that we have to be mindful of some of the issues that we’ve dealt with over the last decade. One of those being the amount of violence and sexual assault that we have seen on college campuses across America.”

King said it’s not the petitioners’ responsibility to present an alternative to ACSO.

“These are demands from the community. I’m a professor. I’m not going to come up with the solution. The exact details of what the new security [is] — that’s not my expertise,” King said. “I’m calling upon the governing body of the Peralta colleges to come up with the solution. That’s their role to do that.”

Reframing safety

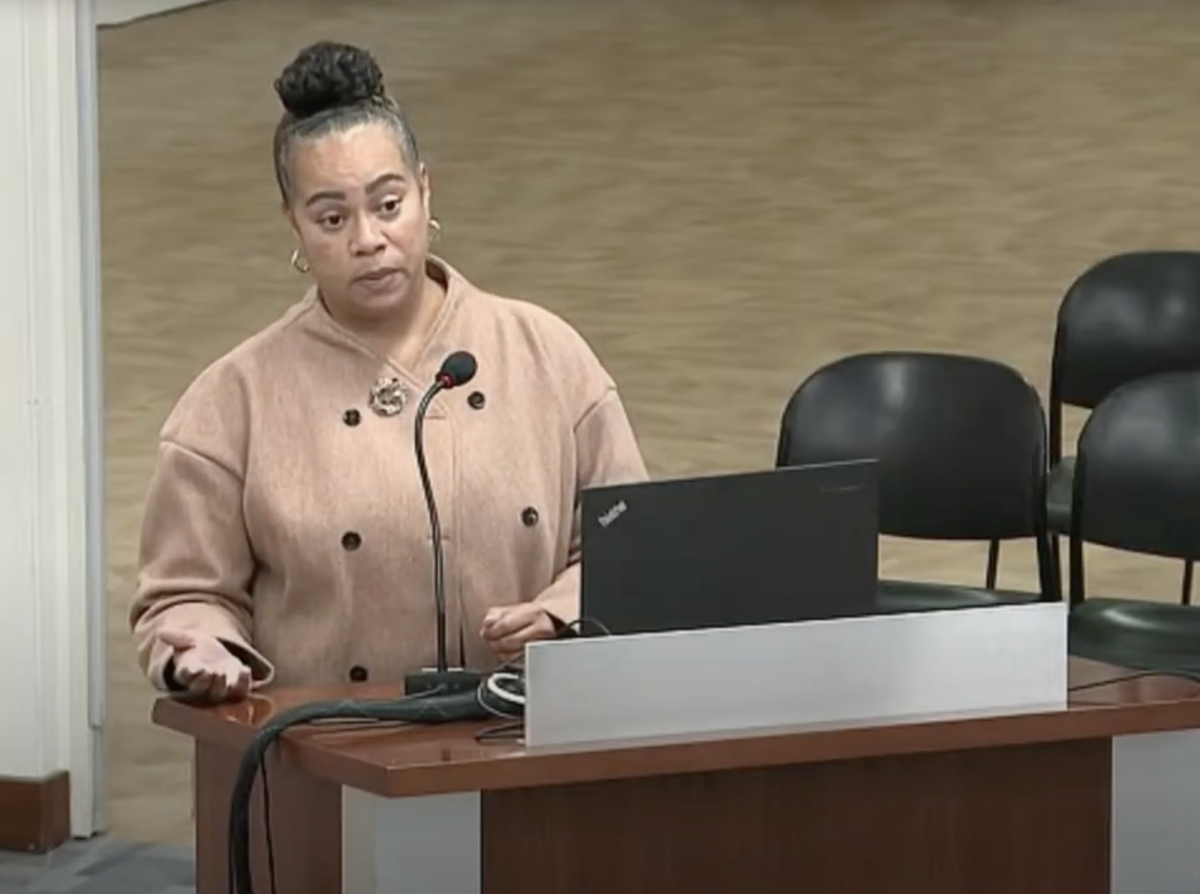

At an April 27 virtual security forum hosted by Laney College, attendees were encouraged to rethink their definition of safety. Laney College President Tammeil Gilkerson presented findings from the virtual gathering at the June 9 board of trustees meeting, highlighting that safety isn’t just preventing physical harm. Attendees of the security forum also expressed a need for emotional safety, relational safety with the law, identity and status safety, and security in obtaining basic needs, Gilkerson said.

Chung emphasized that before the district commits to a contract, the Peralta community should come together to develop a concrete definition of safety.

“I feel like it’s not on one person to say we should have this instead of the sheriff,” he said. “I think, you know, the community really should come together and define exactly what makes them feel safe.”

Protecting students who feel uncomfortable because of “historical and traumatic experiences with law enforcement” should be a factor in developing a security plan, Chung said. That includes people currently on supervision, previously-incarcerated people with a conviction record, and undocumented people.

“I think that the district really needs to kind of evaluate the extent to which every single person that they’re welcoming onto that campus feels safe using that security system to advocate for their own safety,” he said.

Plans from the district

Though calls to defund traditional law enforcement presence on campuses have increased in light of nationwide protests against police brutality toward Black and Brown people, conversation about reform in Peralta’s security services began a year ago. After contracting with ACSO for over two decades, the board of trustees failed to re-approve the annual contract in May 2019.

Kelly said that until then, ACSO and Peralta had a fruitful and mutually beneficial partnership.

“Our interactions with the students and the community and the administration and the faculty has been — over the last almost-three decades — very, very good, very strong, and a lot of our people have enjoyed working there,” he said.

This is Deputy Bridges at Laney College handing out water to those in need. He is just a thoughtful person. After two days of extreme temperatures in the Bay Area, his good deed was welcomed by many on campus. pic.twitter.com/boD8u7pjWW

— Alameda County Sheriff (@ACSOSheriffs) June 11, 2019

According to a security survey presented June 9 to the board of trustees by Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs Siri Brown, the relationships established between police officers and people on campus is mixed, with 66% of respondents claiming that officers are only “somewhat” “a little” or “not at all” involved (this survey had 528 responses). However, 85% of respondents reported feeling satisfied in their interactions with the police officers stationed at Peralta (this survey had 218 responses). The most recent enrollment data available on the Peralta website reported a total enrollment of 37,778 students in 2017.

Laney counselor and faculty member Greene said that he has not seen police brutality by ACSO during his 20 years at Peralta.

“Not to say it won’t happen — cause anything can happen these days — but during my time, it’s not like we’ve had, like, these major clashes with the Alameda County Police Sheriff within the district,” Greene said.

The petition references a 2018 statistic showing that Alameda County defended more civil rights cases than all neighboring counties.

When the board didn’t renew the contract with ACSO in May 2019, it was reconsidered a week later and approved with the understanding that the district would develop alternatives to traditional law enforcement presence on campus over the following year. In an email to The Citizen, Trustee President Julina Bonilla said that board requests included cultural competency training for ACSO at Peralta, apprenticeship opportunities for students interested in law enforcement, community policing alternatives to armed policing, and constructive dialogue opportunities between ACSO, students, faculty, and staff.

On May 12, the board approved a $31,500 contract with Anthony Finnell, a former police sergeant, to develop alternative security models for Peralta. Finnell previously served as the Executive Director of the Oakland Police Commission, along with Trustee Meredith Brown who served as legal counsel for the commission.

Developing the model included analyzing surveys and previous crime reports that happened on or near the campuses, and interviewing staff, administration, law enforcement representatives, and city counselors, Finnell said.

“We took all that feedback and determined that the vast majority of people and the common theme was to have a hybrid model,” he said, which “heavily incorporated a community-based component that was skilled in de-escalation, [and] also had a mental health component.”

In an email to The Citizen, Stanback Stroud said that the model presented on June 9 was developed also using the “wisdom and expertise” of Restoring Our Communities members and drew “from the perspectives of racial and cultural affinity groups.”

The resulting model proposed to eliminate all ACSO presence on College of Alameda and Merritt College campuses and would incorporate a private security guard service, student security aides, and potentially a community-oriented security team on all four campuses. Because of the higher crime rates on and surrounding Berkeley City College and Laney College campuses, Finnell suggested continuing Peralta’s contract with ACSO for those campuses.

The model, estimated to cost $5.4 million, could result in 11.4% savings from Peralta’s current $6.1 million security plan, Finnell said. The number of campus personnel would be reduced from the currently stationed 15 officers. The contract with ACSO would be reduced to $3.2 – $3.8 million, depending on the board’s chosen scope of work. Other security services costs would increase in replacement of where ACSO was previously stationed.

“There are several alternatives that can be pieced together in this one model,” Stanback Stroud said following Finnell’s presentation. The level of ACSO, private security, and student aide involvement are open to adjustment, she said.

Board considerations and requests

Though many trustees said they appreciated the hybrid model, the administration’s proposed security plan was followed by nearly an hour of debate from the board. Board Vice President Cindi Napoli-Abella Reiss and President Bonilla both asked for more alternative models — including one without ACSO presence. Four additional models representing these requests will be provided at the June 23 meeting.

Napoli-Abella Reiss said that she is unsure of how to move forward with ACSO. “Fifty percent of my voting constituents have conveyed their security concerns and they want the contract to move forward; fifty percent of my constituents also say, very emphatically, cancel the contract with ACSO,” Napoli-Abella Reiss said.

Noting that the district plan is the “most interesting alternative that I think we’ve seen,” Trustee Nicky González Yuen said he’d like to use shared governance to get student, faculty, and classified input. He also said that he hopes the board can have more time before voting on the year-long contract with ACSO.

“I am sincerely hoping that we are not going to be in the position of having to do an up-or-down vote at our next meeting,” González Yuen said. He asked that the administration find a way to continue the contract with ACSO month-to-month in order to give the board more time.

Trustee Brown called for more transparency and repeated her request that Peralta reinstate a committee to help develop a security plan.

“I think that we have to be intentional in saying we don’t want racism, yet we close off the community that are predominantly people of color by not having a committee,” Brown said.

An anticipated vote

During the June 9 meeting, Chancellor Stanback Stroud told the board that the proposal had been developed prior to the petition but that implementing a hybrid model could be a first step toward discontinuing relations with ACSO. The way institutions start defunding traditional law enforcement on campus is “precisely the way in which we brought it before you today,” she said.

If the board were to cut ties with ACSO, no one would lose their job, Kelly said. The officers currently stationed at Peralta would be reassigned to other divisions.

ACSO would be “very, very sad to no longer be a part of that community,” Kelly said. “The real loss would be our relationships that we built over 25 years at the college.”

However, with more than 1,000 signatures and plans to fill public comment at the June 23 meeting, supporters are determined to sever that relationship.

“We understand how the community feels,” Kelly said on behalf of ACSO. “We’re listening.”

Though Kelly agrees that “there are people within law enforcement ranks that need to be gone,” he is adamant that defunding police is not the solution.

“I know that the current climate is to be very anti-police on campus. But I think that there will be costs associated with banning police from campuses.” Kelly said he thinks that reform is still in reach and can be achieved with open-minded communication and fresh participation in law enforcement.

“We should be working in this together as one community,” he said. “It shouldn’t be the police versus the students.” If people want to change the culture of law, “we need to have individuals — college students — join our ranks, and join this profession and be part of the reform, and not talk about it, be about it,” Kelly said.

Mark Johnson, interim executive director of public information, communication and media, advertised a “Campus security and community policing” webinar on June 22, scheduled for June 23 at noon.

Merritt College offers an administration of justice program, and President David Johnson said that he plans to host a “Black and Blue” forum to spark conversations regarding education, policing, and race in the coming weeks.

However, supporters of the petition are not satisfied with police reform and are demanding more.

“As part of our humanity, we need to show up for this movement,” Associated Students of Laney College President Raya said of both students and teachers.

“The ideal community college teacher is a teacher activist, in my eyes,” she said. “They’re teaching a demographic of students who are literally on the frontlines of these issues.”