On March 23, the Peralta Community College District closed all four campuses due to COVID-19, which left many instructors scrambling to learn and navigate the complexities of Canvas and Zoom. Despite the mandatory utilization of these resources in the spring, instructors are still discovering how to benefit from these unfamiliar platforms one semester later.

Merritt College English instructor Jon Drinnon, who has been teaching for 20 years, was uncertain about how his critical thinking and English 1A classes were going to work in an online environment.

“What was going on in my head was, ‘I don’t want to do anything about this. I’m not an online teacher, I’m not going to do this — they can’t make me teach online,’” Drinnon said. “I realized, ‘Hey, this is bigger than me, it’s bigger than them.’ We all have to pitch in for the sake of the students, and there’s no way around it.”

Although originally opposed to the idea of distance learning, Drinnon realized he had to restrain his initial feelings of teaching online and his concern shifted toward his students. Drinnon was motivated to spring into action and decided to take classes at Merritt to learn how to work and operate Canvas. He spent 12 hours a day online to make the transition.

His efforts paid off — Drinnon realized he could achieve more online than in person. He said he could interact with his students more and that they participated more in class discussions. He was able to grab the attention of his students by pairing his lessons with videos on Canvas. Overall, he felt online education had given him more flexibility with his approach to teaching.

When the fall semester started, Drinnon was surprised to find out about more tools that Canvas offered. He found that his material naturally fell into the Canvas model.

“Everything that I do normally kind of fit into that model, all I had to do is learn how to put it up and learn how to make it happen in terms of Canvas. It’s really great, it’s got all the tools you need,” Drinnon said.

Although he feels the fall semester has been successful, Drinnon still has many concerns for his students regarding online education, their safety and the resources available to them.

Like Drinnon, Laney College Political Science Instructor Scott Godfrey also had concerns. In his classroom, Godfrey said he works on creating bonds with his students, but this has become increasingly difficult through a pixelated screen. Godfrey said he cares deeply about his students and believes it is important to build online communities that allow students and educators to communicate and feel connected during this time.

“For those of us who have already had a fair amount of experience teaching online, one of the things that we learned is how to build online communities — and to communicate to your students that you care about them,” Godfrey said.

Godfrey emphasized the importance of community bonding. He said the emotional toll on students and colleagues who had no prior online teaching experience concerned him.

Godfrey aims to communicate regularly and be sincere with his students. He often sends well wishes and attempts to maintain the communication he would normally have during face-to-face classes.

Unfortunately for many instructors, the transition has been anything but easy. The work that goes into an online class is stressful. For instance, instructors now have to be in constant communication with students, learn new programs, hold scheduled meeting times, and assist students virtually in finding the resources they need to succeed. The workload is immense and operating a full-time course online intimidates some professors.

At Berkeley City College, adjunct mathematics instructor Daniel Najjar could have been one of the colleagues Godfrey was worried about. When Najjar heard classes were transitioning online, he said he felt exasperated.

“I almost quit. I almost quit, which was an expression of how anti-online I was,” Najjar said, reflecting about how he recalibrated his traditional mindset.

“My image of online courses was based on what online courses had been pre-pandemic. Online coursework was, as you know, ‘distance education,’ and the whole concept was ‘you don’t have to meet with us,’” Naijar said.

“As a person who focused on providing extra support for failing math students, that was entirely objectionable to me and seemed inconsistent with the concept that I had spent 10 years focusing on.”

When he realized he could emulate face to face interactions remotely, Najjar said it wasn’t as difficult as he believed. Najjar explained that he didn’t have to conform to the traditional idea of “asynchronous” online teaching, and instead embraced “synchronous” learning that enabled him to lecture online in real-time to a class of online attendees. He implemented more through Zoom than he could in a traditional classroom and was relieved to discover he could imitate a face-to-face classroom.

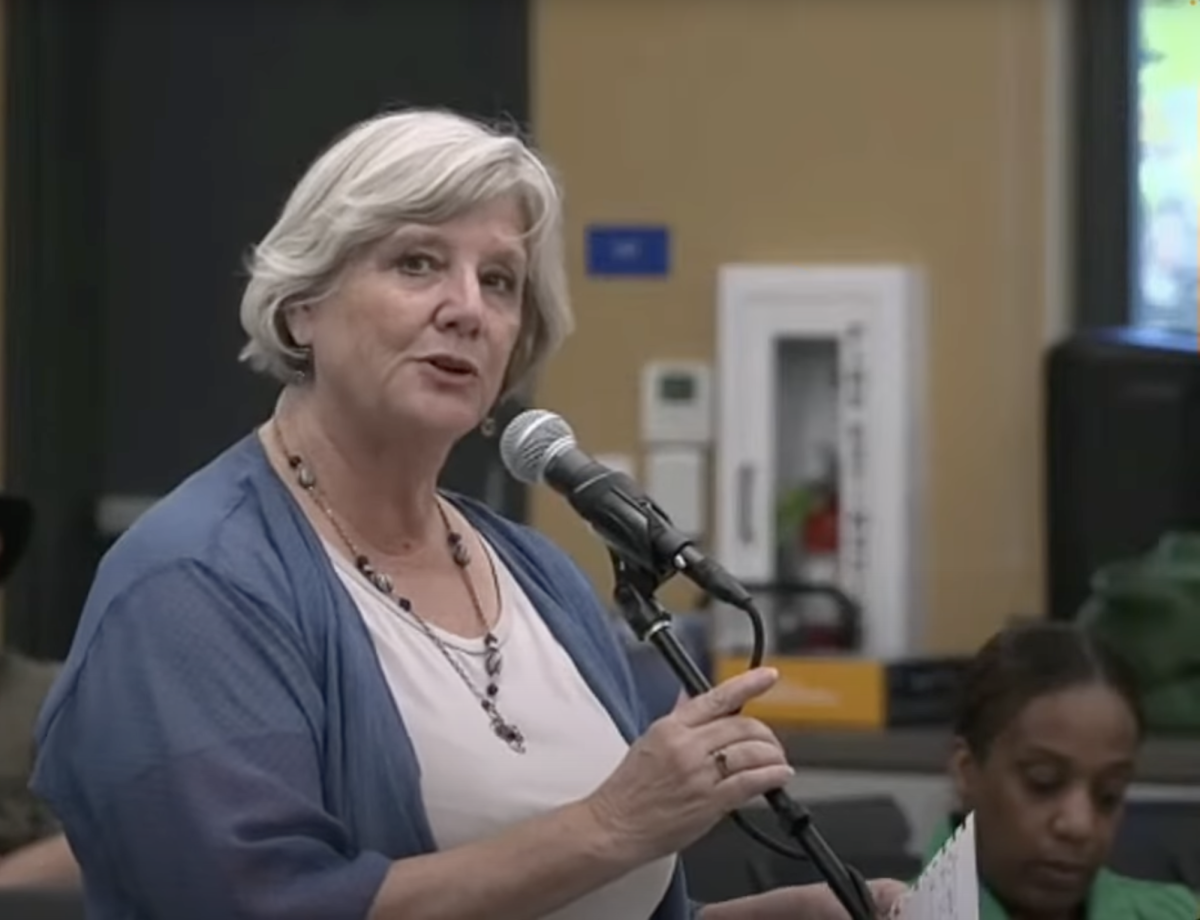

With spring 2021 set to be mostly online at Peralta, one thing is for certain: learning will continue to take a new shape. Jayne Smithson, who teaches anthropology at the College of Alameda, said the most important strategy when it comes to online learning is communication. Having that ability can be a necessary component to attaining academic success during the pandemic.

“Somehow, the students need to get in contact with their instructors,” Smithson said. “ I see that one of the few remaining problems with online learning is the disconnect between the resources that are available, and the people learning how to access those resources. Communication is crucial.”

Throughout this pandemic, many Peralta faculty have dedicated hours to find innovative ways to reach and adequately serve students virtually. The effort is ongoing, and perhaps some have learned strategies that they will continue to utilize post-COVID.