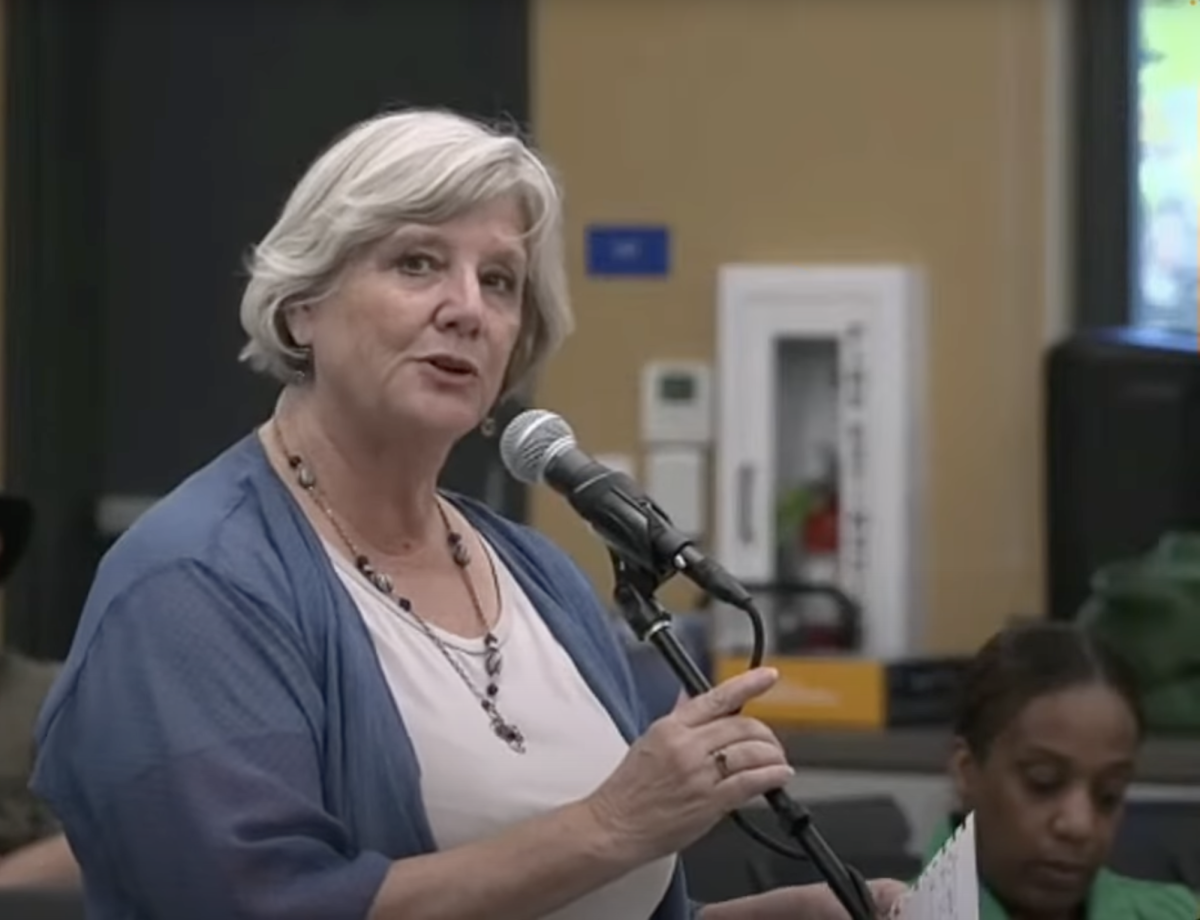

by Toni Cervantes/Tower Staff Writer

It was 1968: a tumultuous year in both politics and sports. It was the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games. And I was member of the United States Olympic Swimming Team.

It was the year that changed the world.

Two athletes, Tommie “Jet” Smith and John Carlos, who were stars of the United States Olympic Track and Field team, sacrificed everything to bring attention to racial inequality and segregation in America.

Little did I know, their act of defiance would be the beginning of my lifelong commitment to social justice.

I was 17-years-old. I qualified in two events — the 100- and 200-meter butterfly. I had the fastest time in the world going into the games, and Sports Illustrated had predicted I would bring home the gold in the 200.

The events of that year cracked my political awareness wide open; the Vietnam War death count was broadcast on the nightly news.

The Black Panther Party, farm workers, the American Indian Movement and feminists were spilling into the streets demanding to be heard; the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., shook the country to its core.

The world as we knew it was turning upside down in 1968.

Ten days before the Opening Ceremonies, the Mexican government launched an offensive against students who had gathered at Tlatelolco Plaza to protest police violence. The army used bulldozers to disperse the crowd.

A deadly shootout in the Plaza followed.

Consequently, the games were in danger of being cancelled, but the Mexican authorities managed to bury the depth of the atrocities by reporting the deaths of only four students. According to an NPR report, the unofficial number of civilian casualties could be as high as 3,000.

I was vaguely aware of the confrontation between the students and the army in Mexico, but I was well aware of the controversy over the looming boycott planned by the African American members of the track and field team. I had received a letter at training camp detailing the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) agenda from Dr. Harry Edwards, who was spearheading support for the boycott.

This threat, of African American athletes boycotting the Olympics to challenge racism in America, enraged the Establishment. Jesse Owens, the African American hero of the 1936 Berlin Games, tried to reason with the track team and get them to abandon the protest. It created a rift between Owens and and Smith that never healed.

Prominent leaders of the civil rights movement backed the boycott. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. even met with Carlos in Mexico to offer his support just 10 days before being assassinated in Memphis, Tenn. The boycott never materialized.

Smith went on to win the gold in the 200 meters. His time of 19.83 seconds shattered the world record. Peter Norman, a caucasian runner from Australia, won the silver medal, while Carlos received the bronze.

What transpired after the race sent shock waves throughout the sports world that are still being debated today.

The medal ceremony commenced with the playing of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” All three medalists wore an OPHR button alongside their Olympic medals.

Smith also wore a black glove on his right hand to symbolize black power and a scarf to represent black pride. Carlos wore the other black glove on his left hand to symbolize black unity. He wore beads around his neck in remembrance of all those who had been lynched, murdered or tarred, and he kept his jersey unzipped in solidarity with blue-collar workers.

Both Smith and Carlos stood on the podium without shoes, their black socks pulled up to the knees, to remind people of slavery and Black poverty in America. As the National Anthem played, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads.

Smith raised his right fist and Carlos his left. The infamous Black Power salute captured one of the most iconic moments of the 20th century.

America rejected the silent protest. Smith and Carlos were booed from the stands, kicked off the team and forbidden to race in the other events they had qualified for.

I witnessed them being dragged out of the dormitory, manhandled like criminals, and banned from the Olympic Village where the athletes were housed. I was in disbelief.

Smith and Carlos returned home to an ungrateful nation. They and their families were met with death threats. Many of the Black athletes who brought glory to America couldn’t even find jobs upon their return from Mexico City.

Norman, the Aussie who won silver, paid dearly for supporting Smith and Carlos. He was not selected for the 1972 Australian Olympic Team, even though he was their fastest runner. He never recanted his actions in Mexico City, and Australia never forgave him while he was alive.

When he died in 2006, Smith and Carlos were pallbearers at his funeral. All three men are heroes to me.

The track and field events had taken place in the first week of the Games, and the swimming events followed the dramatic seizure of the two runners.

Naively, I had become friends with a few athletes on the U.S. and Caribbean track teams. I thought that bridging the cultural divide was one of the highlights of the “Olympic Spirit.”

After the trouncing of Smith and Carlos in the press, those innocent friendships I had made created an uproar among the coaches and management on my team. A few days before the biggest event of my life — races for which I had arduously trained eight years — the whole thing seemed like it was about to go down the drain.

The coaches and the managers from the swimming federation held meetings to consider expelling me, a Native American, from the Olympic team. All this, because I had made friends with track and field athletes who happened to be Black.

I was allowed to race, but I placed a disappointing fourth in the 200-meters butterfly and seventh in the 100. I blamed myself for my failure and was ashamed to have let my family, my coach and my country down.

Years later, I realized that it was the other way around — my country and my team had actually let me down.

Most recently, Colin Kaepernick and other athletes taking a silent knee to bring awareness to the epidemic of police brutality against African Americans still stirs outrage. Kaepernick’s symbolic gesture has divided and galvanized the country like nothing else since that October day in 1968 when Smith and Carlos gave their “Human Rights” salute.

I wonder — how far have we really come in 50 years?