Black Panthers doc wows, but falls short

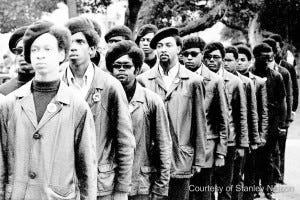

Beneath twin screens projecting scenes from Stanley Nelson’s new documentary, The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, former Black Panthers Party Minister of Culture Emory Douglas settles into his seat at the American Institute of Graphic Arts headquarters in San Francisco. Stills of his evocative, powerful art flash and awe the small but rapt audience before him.

Douglas, now a 72-year-old world-renowned artist and graphic designer, didn’t quite get his start with the Panthers, however; his journey to revolution began at a local community college.

Douglas’s studies at City College of San Francisco propelled him straight into the heart of the era’s Black Arts Movement; when, in 1967, when Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz, came to town, Douglas was tapped to design the event’s flyers, ending up a planning meeting that would change his life.

“When I went, they were talking about some brothers doing security for that event, coming over,” he says. “When they did come over: that was [Party co-founders] Huey Newton and Bobby Seale.”

“It was because of the climate of the country during that time — the same as it is today, a lot of police murder of young Blacks always being justified,” he says of what happened next. “Young people were frustrated, trying to find out… what they could do to change the situation, get involved. When I seen Huey and them after the meeting, I knew that’s what I wanted to be part of.

“I asked Huey and Bobby, how could I become involved, how could I join. They gave me their card.”

The rest is history.

Who Was Huey Newton?

“To me, there was only one reason to read the Panther newspaper, and that was to see Emory’s illustrations,” Felipe Luciano, a former member of the Young Lords, says in the documentary. “His paintings — his caricatures, his illustrations — literally gave us the story!”

These images are indeed dazzling: and not just those of Douglas, but also those that Nelson has compiled in “Black Panthers.” The film mesmerizes, swelling viewers up with the revolutionary spirit of the era. Yet with a limited runtime of just under two hours, what Nelson’s documentary gloriously achieves in breadth it ends up sorely lacking in depth.

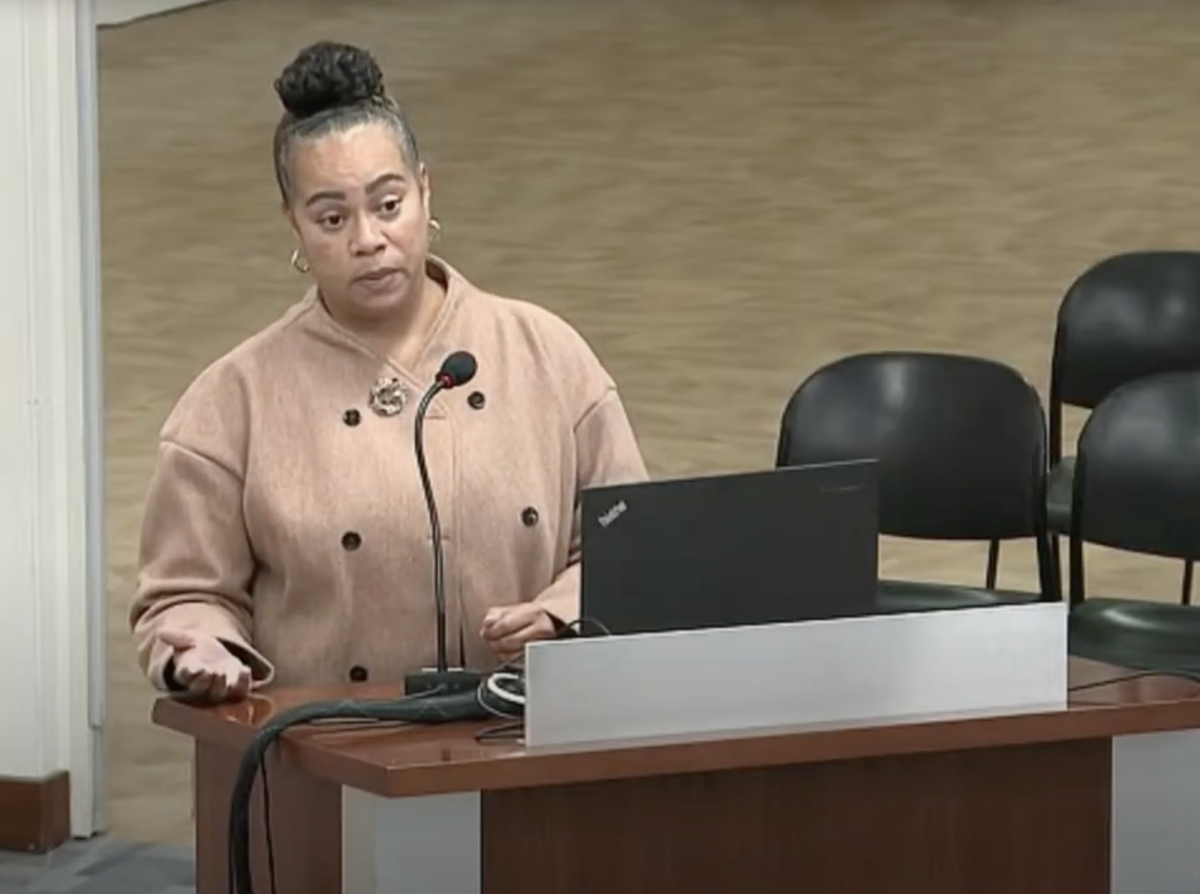

For example, although many of the film’s interviewees are women, only a small segment of the film is devoted to the problematic gender dynamics at play within the Party. The Party was largely comprised of women, yet female members found themselves dealing with violent sexism — from within their own organization. “We didn’t get these brothers from revolutionary heaven,” former Party leader Elaine Brown says in the film. Testimonies by Panther members like Katherine Campbell, Madalynn Carol Rucker, and even Brown herself reveal how some male Panthers harassed and assaulted — sometimes sexually — female members of the Party. In “A Taste of Power,” her memoir, Brown tells of ten lashes she received after a minor misstep. “Discipline was essential in the vanguard, we told ourselves,” she writes. “So I silently faced the punishment, which was always an act of violence.”

Testimonies by Panther members like Katherine Campbell, Madalynn Carol Rucker, and even Brown herself reveal how some male Panthers harassed and assaulted — sometimes sexually — female members of the Party. In “A Taste of Power,” her memoir, Brown tells of ten lashes she received after a minor misstep. “Discipline was essential in the vanguard, we told ourselves,” she writes. “So I silently faced the punishment, which was always an act of violence.”

Moreover, the film desperately calls out for the voice of Party co-founder Bobby Seale, who is palpably absent from the film. CommonDreams.org reported that, following a screening of the film, Seale gave the documentary “a rating of 5 on a scale of 10.”

The film’s treatment of the Party’s other co-founder, Huey Newton, also left many frustrated. Newton is mostly relegated to the film’s beginning and end, spending most of the film’s winding, semi-chronological narrative in prison. And though he is presented at first as a charismatic leader, his philosophical depth and strategic prowess are obscured almost completely.

“Society responds to [the Black man] as a thing, beast, nonentity, something to be ignored or stepped on,” Newton writes in 1967, at age 25. “He is asked to respect laws that do not respect him. He is asked to digest a code of ethics that act upon him but not for him.”

This kind of incisiveness gets lost in the film, especially as it tracks the decline of the Party — and what it portrays as the decline of Newton himself. Elaine Brown, former head of the Party, obliterated the documentary in a Daily Beast review, saying that, by its end, the film reduces Newton to “a thug and a drug addict.”

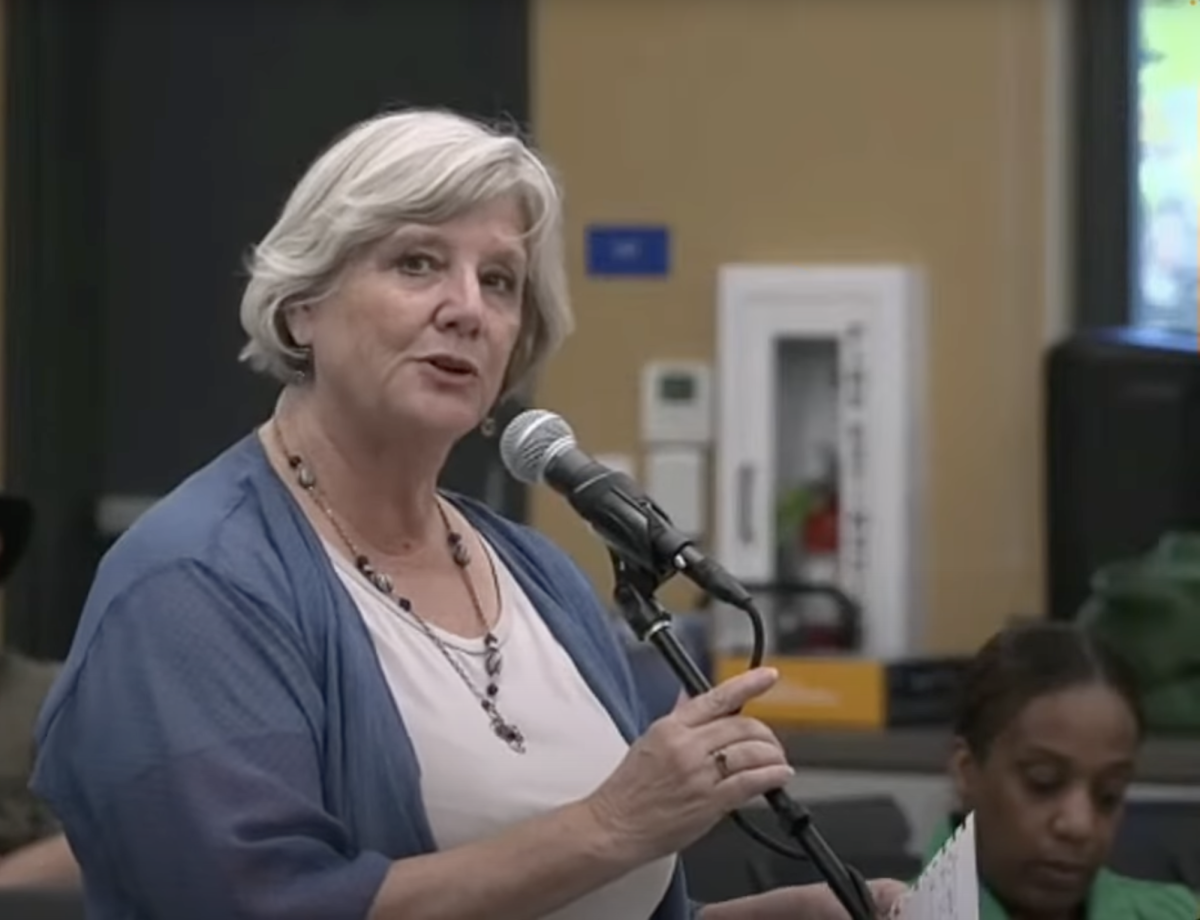

Indeed, during a discussion with Nelson and Steve McCutchen, a former Panther, after the Oct. 3 screening of the film at Oakland’s Piedmont Theatre, an audience member asks Nelson why he chose to present Newton this way.

Although Nelson’s answer is unsatisfying — “I presented Huey the way we found Huey to be” — McCutchen is tactfully emphatic about the complex figure.

“What he shared when he was around the general membership of the Black Panthers Party — he brought those feelings, those visions, those concepts,” McCutchen says.

“Those people who were only around Huey because they wanted to be in the limelight with him… did not know Huey P. Newton. I and many others knew him for what he was, as co-founder and chief theoretician of the Black Panthers Party. That is the part of Huey P. Newton and that so much more so needs to be emphasized and brought out.”

“Absolutely Free”

But the film is very effective at emphasizing and bringing out the Panthers’ innovation and dedication. Early on, the film spotlights an intense confrontation at the Sacramento State Capitol building — it seems as unfathomable today as it might have back then to imagine a group of armed Black men walking into a government building to protest injustice — that catalyzed for many a path straight toward the Panthers Party.

From there, the film races onwards, showcasing powerful imagery from the Free Breakfast for School Children Program — which served as the inspiration for today’s federal program Head Start — and the People’s Free Medical Centers, providing urgently needed services — like free testing for sickle cell anemia — in a time not so unlike our own, when Black Americans couldn’t call 911 without fearing for their safety.

The film also harnesses the youthful charisma and bridge-building potency of 21-year-old Fred Hampton, before his brutal murder at the hands of the colluding Chicago Police Department and FBI. And the film captures the lively grassroots campaign of Bobby Seale and Brown for the offices of Oakland Mayor and City Council member, respectively, before their ultimate defeat — and soon, the end of the party itself.

But as the film comes to its climax, we see the intensity of the party play out most vividly in a grand stand-off, in the heart of 1969’s downtown Los Angeles, when a police force prepared to use any means necessary to bring down the Party once and for all faced a group of Panthers ready to defend their territory and their dignity.

The culmination of the film, however, isn’t this sensational event; it’s the defiant words of Panther Wayne Pharr, when asked how he felt in the thick of the battle.

“They couldn’t get in. I couldn’t get out. In that little space I had I was the king,” he says.

“I felt free. I felt absolutely free.”

A New Vanguard

“It was a reflection of [the Panthers] in the artwork itself, because you were putting them onstage as the characters, as the heroes,” Douglas says in the film. “They could see their brother or they could see their uncle in the images.”

Even if they can’t see any of their own family members in the film, Oakland residents will certainly see their city reflected back at them; the conditions that were ripe for revolution in Oakland of 1965 are eerily yet unsurprisingly similar to the conditions of Oakland in 2015.

So then where are the modern-day Panthers? Where is the radical revolutionary that will hand his business card to a captivated moviegoer at a local theater or a curious student at a community college?

At a forum with Nelson following the Oct. 3 screening of the film at Oakland’s Piedmont Theater, Nelson tries to answer this difficult question. “The Panthers were meant to be an inspiration,” he says, “not a model.”

This is where the power of Nelson’s documentary lies: we may not need another documentary like Nelson’s, with its bird’s eye view of dozens of dramatic and fascinating aspects of the Black Panthers Party, but each of these aspects seems to cry out for its own documentary and study in turn.

The old guard — Douglas or McCutchen, Seale or Brown — would certainly have no shortage of tales to tell. And their stories, along with Nelson’s, will surely shape the way today’s Oakland tells its own tales when it looks back on its vanguard of a new revolution — wherever it might be.