Archie Williams looks cool: black t-shirt, black jeans, slouched beneath a grey beanie, eyes hidden behind dark sunglasses, his large biceps crossed loosely across his chest as he leans back casually in the Laney Cafeteria. Williams does not look out of place on campus. His calm demeanor does not betray he spent the last 36 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

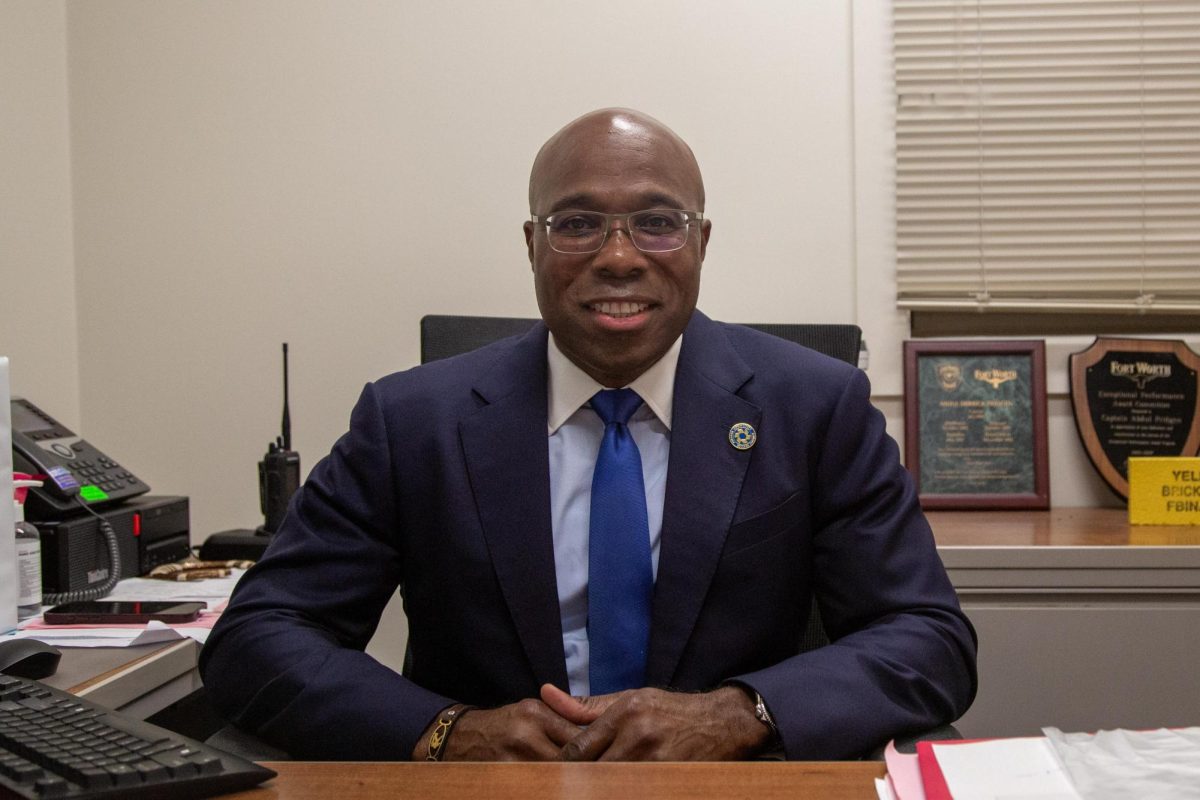

Restoring Our Communities (ROC), a program assisting students impacted by incarceration, hosted a tour of Laney last summer. ROC Student Services Specialist Vincent Garrett recalled Williams was passing time on Laney campus when he decided to attach himself to the tour. Williams was unaware of the center’s intention, but by the end of the tour, Garrett had signed Williams up for fall classes on the spot.

“[Archie] is a real humble dude,” Garrett said.

“Despite the challenges ahead of him, he remains very optimistic.”

Garrett said he felt it was a real stroke of luck that Williams found himself on campus that day and on the tour — the first of its kind. Garrett said ROC now hopes to conduct the tours every semester.

Williams was exonerated with the help of the Innocence Project. Founded in 1992 by Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck, the Innocence Project’s aim is to use DNA evidence to exonerate wrongly convicted individuals and help reform the justice system. As of the writing of this article, the Innocence Project has helped exonerate 367 innocent people, including Williams. Williams proved to be one of the longest cases the project has ever worked on.

Born in the summer of 1960, Williams lived in Baton Rouge, Louisiana with his three sisters and two parents.

“I was just a bad little rascal, running around trying to figure out life,” Williams said.

The first time Williams was arrested, he was 12 years old and trying to steal a bicycle. He was the youngest person in the detention center, but Williams said this was normal, and he was always trying to keep up with the older guys.

At age 15, Williams learned the roofing trade, but it was his job at a fish market at age 18 that would lead to his first incarceration. After an altercation with the owner of the fish market, Williams had some drinks and broke into the man’s house. He was arrested, accepted a plea bargain and spent a year in the Parish Prison and a year in Elayn Hunts Correctional Center (EHCC).

EHCC, referred to as “Hunts” by Williams, opened in 1979. Named after the first woman head of corrections in Louisiana Elayn Hunts, who believed strongly in prison reform. Hunts strove to reduce prison violence and this philosophy was followed by her predecessors after her death in 1976.

Six months after his stay in Hunts, Williams was leaving his aunt’s house to return to where he had been staying with his mother. Police ran up to a confused Williams, drew their weapons, and arrested him. He would be charged with aggravated rape, attempted murder, and aggravated burglary. Williams’ trial lasted five days and five nights, and he was found guilty and sentenced to life plus 80 years.

Williams said he was the victim of “malicious prosecution” and said the husband of the victim had been friends with the judge since childhood. He was sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary, on January 4, 1983.

Louisiana State Penitentiary resides on the land that was occupied by the Angola plantation, named after the country in Africa where many of the slaves that worked the plantation originated. The penitentiary is commonly referred to as Angola, and many of the inmates there work the land under similar conditions to the plantation era. Angola has been run by a series of corrupt wardens and is known for brutal conditions for prisoners.

After his time at Hunts, Williams said it was easy to adjust to Angola. He said things were different when he entered the prison in 1983 than when he left it.

“At that time, inmates ran the prison,” said Williams.

Corrections officers, who were called “free-men,” left almost all responsibilities to inmates, allowing for violence and corruption.

Williams tried to avoid this by singing in the choir and joining the prison’s boxing program.

Williams had begun boxing while in EHCC, and trained under a successful boxer in Angola. He used what he learned to create an undefeated boxing program at Angola in the 90’s. Williams continued with the program until the mid-90’s, when he first heard of the Innocence Project, and his focus changed.

“I first heard about DNA somewhere around ’89 that there was this test that can tell facts,” recalls Williams.

In 1995, Williams met someone inside the prison who told him about the Innocence Project. Williams had made copies of his court transcript in large quantities and sent a copy to the Innocence Project. Three months later, the Innocence Project agreed to take his cases, but it would take another 23 years for Williams to be released.

The Innocence Project immediately saw problems with Williams’ case. Williams was included in a photo array shown to the victim, who did not identify him as her attacker, but she told police they should look for a suspect who resembled Williams. The victim, who was 5’ 7”, testified that the assailant was taller than her. A 5’3” neighbor who interrupted the crime, who was wearing three-inch heels at the time, also testified that she saw a man taller than her. Williams, 5’4”, did not fit this description.

In addition, Williams had an alibi — his mother, sister, and family friend all testified that he was asleep at home when the attack occurred.

DNA evidence for Williams’ case was requested by the Innocence Project when it was first made available in 1996, but would take 10 years for a law to be passed that allowed Louisiana prisoners access to DNA evidence. A rape kit collected at the time of the attack was not tested until 2009, but the DNA collected did not belong to Williams. The only DNA found in the kit belonged to the victim’s husband, and since this evidence could not incriminate a new suspect, Williams was left in prison.

After this setback, the Innocence Project tried another type of forensic evidence, fingerprints, to exonerate Williams. Although there were prints left at the crime scene, there was no statute that allowed prisoner access to this evidence after conviction. The first forensic lab was unable to find a match for the fingerprint evidence.

The second lab, Next Generation Identification (NGI), was able to match the fingerprint to a new suspect in 2014. But this was not allowed to be used as evidence until 2019, at which time it was used to prove Williams innocent, and he was released.

The print that NGI submitted to the database identified a known individual named Stephen Forbes. Forbes had been arrested in June of 1986 for attempted rape, two miles away from where Williams had been wrongly arrested. After his arrest, Forbes confessed to four other rapes between 1985 and 1986. Forbes died in 1996 without ever being questioned about the attack that Williams was spending his life in prison for.

To add to being falsely imprisoned and having forensic evidence ignored by the legal system, Williams was placed in solitary confinement from 1997 until his release in 2019. Williams said he believes this was retribution by the warden, Burl Cain, who resented him for leaving the champion boxing program inside Angola.

On the torture that is living within solitary confinement Williams said, “I believe freedom is of the mind, that is how I was able to endure what I was able to endure — I’m not going to help you destroy me.” Williams said he has strong faith in God, trusting that everything has happened for a reason, and he is now where he is intended to be.

This mindset could explain how Williams came to find himself enrolled full time at Laney College.

With family in the Bay Area, Williams says he is “all California now,” and Louisiana is in the past. William has continued playing music. He started playing music at age 12, singing R&B songs with a band at local night clubs. “I was the little Michael Jackson,” Williams remembered. He is currently enrolled in a piano class and a voice class at Laney.

Since his release, Williams has been to perform at the Apollo Theater in New York City. He looks forward to returning to the Apollo Theater to perform. When he spoke of his performance, a large smile lit up his face, and scrolling rapidly through his phone, he shared a picture of his first visit there — his name illuminated on the marquee.

It has taken 36 years to get Archie Williams where he belongs.