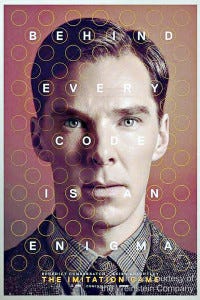

Cumberbatch and Knightley star in WWII espionage drama with splashes of comedy

British mathematician Alan Turing posed a simple question: “Can machines think?”

Set primarily in Southern England during World War II, Morten Tyldum’s “The Imitation Game” sets out to explore this brilliant mathematician and code breaker whose ideas were essential to ending

the war. The film features Keira Knightley (of “Pirates of the Caribbean” fame) as Turing’s confidante and shortlived fiancée and Benedict Cumberbatch (Sherlock) as Alan Turing, the enigmatic

but brilliant beyond measure cryptologist.

Cumberbatch is stunning in his role as a socially ill-equipped genius, capturing the tics and mannerisms associated with individuals with severe mental problems — although in real life Turing

was apparently far more willing to accept criticism and assistance. The film examines several interesting themes: morality, war, skepticism of new technology and, ultimately, change in general.

Turing was the man who created and programed the “Bombe” and decoded the Nazi German “Enigma” machine, a cryptographic typewriter that was the key to encrypting Axis radio communication throughout the war.

Turing’s background was in advanced-level mathematics and cryptography, and before the war had gotten his undergraduate degree at Cambridge University and his Ph.D. at Princeton. Between these scholastic ventures, he wrote a paper detailing his theory of “Universal Machines” — machines that could “compute any mathematical formula if that formula is presented as an algorithm”.

These machines, now known as “universal turning machines,” are the basis for the central idea of computing today — the very same computers that this article was written on, this newspaper was designed on, and that you likely carry around in your pocket with you at all times.

The crux of the film was set out to examine fear through the parable of Turing (having either changed or left out much of the actual history of the events) — fear of war, bombs and bullets. There was also fear of death, homosexuality, of being different. Fear was all around, with constant threat of bombings in the short term and Fascist takeover in the long term.

The film also heavily emphasizes the relationships of Turing, the ostensibly narcissistic prodigy. He is ultimately revealed to be not egotistic in the traditional sense, full of grandeur and machismo, but merely pragmatically aware of his abilities and unconcerned with social pleasantries and customs to get his point across, arcane though it may be.

Turing is faced with a terrible dilemma once the machine is built — whether to act on the sensitive intelligence at once (and save 500 innocent souls) or use statistics and probability to decide

which message to act upon and which to ignore. The decision was to keep the fact that they’ve cracked the code out of Fascist earshot (and would remain a classified British military secret for

the next 50 years).

The code breakers use this “bloodsoaked calculus” for the next two years until the end of the war, careful not to overstep their bounds and be exposed (and risk the Germans changing their machine, rendering four years of work useless), playing God as they decided who would live and die, not with the usual cigar-smoking brass pushing model boats around a paper ocean with

a craps stick, but with algorithms and statistics. The theme of ostracization and persecution of the unknown, unfortunately, follow the film to the credits, as it did Turing to the grave

as he committed suicide at the age of 41, a year after being sentenced to chemical castration for the charge of “indecency” (the euphemistic legal term for homosexuality, which was illegal in the UK until 1967 and in many U.S. states until 2003).

Despite the shadow cast over his later years, Turing’s contributions to mathematics, science and philosophy are undeniable. Without him computers, the concept of artificial intelligence would not exist. World War II might have been lost, as well, and even if we had still won, the death toll would have been exponentially higher.