Tanforan Racetrack was site for Japanese internment

Close to 100 people gathered outside of the San Bruno BART Station late Halloween morning. They were not protesting or shopping at the bordering Tanforan Mall but had instead assembled to begin a fund-raising campaign for a permanent memorial to the thousands of people that endured confinement there, without due process, during WWII for the sole reason of being of Japanese decent.

In February of 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order №9066 evicting, stripping of property, and mass incarcerating approximately 120,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast.

Those in the Bay Area were given less than three months to uproot their lives completely and sell off homes, businesses, and any valuables that could not be carried and to report to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, CA. Most buyers knew that the Japanese had no other choice and only offered pennies on the dollar for possessions.

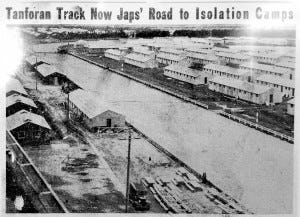

None of the 7,816 individuals who lived at Tanforan had any idea of where they would go or how long they would be gone for. In 1942 Tanforan was a racetrack and grandstand. Detainees lived in horse stalls and make-shift shelters on the infield for three months while permanent interment camps were hastily built in remote locations in the country’s interior.

A fire in 1964 destroyed the racetrack and now the Tanforan Mall exists there. In the 1980s all the temporary detention sites in California were designated as historic sites but the only mention of the past Tanforan Assembly Center lays unobtrusively on a plaque nearby one of the mall entrances.

Among those in the crowd and speaking included members of the Tanforan Assembly Center Memorial Committee, the mayors of South San Francisco and San Bruno, BART Board President Thomas Block, Congresswoman Jackie Speier, State Senator Jerry Hill, a representative from the Japanese Consulate, Pulitzer Prize winning photographer Paul Kitagaki Jr., poet, playwright, and actor Hiroshi Kashiwagi, and television personality Wendy Hanamura who M.C.ed the event with energy and an impressive knowledge of many people present.

Hanamura’s father served in the 100th/442 Regimental Combat Team, a segregated Japanese-American combat unit which fought in Europe during World War II and is the most decorated unit in the history of the US military. Several dozen Japanese Americans that lived through Tanforan 73 years ago were also present alongside their friends and family.  The Tanforan Assembly Center Memorial Committee (TACMC) is a 501(c)3 non-profit is attempting to raise $900,000 to implement a permanent memorial to “ensure that this tragic and illegal action in US history with never be forgotten”. The proposed memorial with feature a statue with the likeness of two children envisioned from the iconic Dorothea Lange photograph of the Mochida family of Hayward as the center piece.

The Tanforan Assembly Center Memorial Committee (TACMC) is a 501(c)3 non-profit is attempting to raise $900,000 to implement a permanent memorial to “ensure that this tragic and illegal action in US history with never be forgotten”. The proposed memorial with feature a statue with the likeness of two children envisioned from the iconic Dorothea Lange photograph of the Mochida family of Hayward as the center piece.

A matching memorial grove and replica of the horse stalls where many incarcerees were held has been designed by the landscape architecture firm of Roysten, Hanamoto, Alley, and Abey (RHAA) in honor of two of their founders who were also incarcerees of the interment camps.

“This memorial will serve as a warning and a caution” declared Congresswoman Jackie Speier, “of repeated actions against those who’s families come from countries that the US is at war against.”

Paul Kitagaki’s father, grandparents and aunt had their photos taken by renowned documentary photographer Dorothea Lange in 1942 while waiting in Oakland for a bus that would transport them to Tanforan. In 2004 Kitagaki started searching for others, largely unidentified, who had their photos for the War Relocation Authority.

He has tracked down several dozen of those who were incarcerated at assembly centers and interment camps and has shared stories of their lives since then. Kitagaki still searches for survivors, many of whom are in their 70s, 80s, and 90s, by showing photos from the National Archives around churches and community events hoping that someone will recognize a friend or family member for him to make contact with. His nationally lauded photo exhibition titled “They Wore Their Best:

The Japanese American Evacuation and After” will be featured in the proposed memorial. This photo exhibit has been on public display inside of the San Bruno BART Station for two years with great reception.

Over two-thirds of the people of Japanese ethnicity interned — almost 70,000 — were American citizens. Many of the rest had lived in the country between 20 and 40 years. Most Japanese Americans, particularly the first generation born in the United States (the nisei), considered themselves loyal to the United States of America. No Japanese American citizen or Japanese national residing in the United States was ever found guilty of sabotage or espionage.

In 1988 the US government formally apologized, concluding that the incarceration of Japanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity and that the decision to incarcerate was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership”.

“Let this memorial serve as a reminder, to all of America, that this cannot and shall not happen again,” finished Steve Okamoto, TACMC Committeeman.

More information can be found at tanforanmemorial.org