Even after resettlement, abused refugee women still find themselves on the verge of homelessness

By Alison Stapp

It was an exceptionally frigid winter in the south of Russia that year.

The temperature clocked in at below zero. Alana (no last name) stood at the foot of the bed she shared with her husband. She was naked and shivering. He had ripped off her clothes and was snuggling comfortably under fur blankets, his eyes coldly roving up and down her naked body. When she couldn’t stand it, she’d plunge underneath the covers, only to be met with his furious fists. The added humiliation of his angry stares would leave bigger scars than the battering around her arms and torso.

No one could see her bruises. That’s how she wanted it. After all, it was her fault. The reason — a strange man had smiled at her while she and her husband were riding the bus home.

The idea that the abused is to blame for violent outbursts by her abuser is just one reason a woman tolerates said abuse.

Her husband’s abusive behavior was often preceded by a night of drinking amongst his friends. She thought that if they moved, he wouldn’t have his drinking buddies and the violence would stop.

Alana, her husband, and their 14-year-old son came to Oakland four years ago. They decided that coming to America would offer a better future for their son. He has just graduated high school, is working two jobs and studying to become an engineer.

Alana has studied over the years and her English is excellent. She trained to become a medical assistant and is now employed.

Other women may be infuriated by why a woman stays with her abuser, but Alana is an excellent example of why the cycle of abuse is so complex.

But the next time we ask a woman why she stays, we might first consider that we are shaming the victim by questioning her motives. We are putting the onus of the responsibility on the woman. We need to consider cultural reasons why she stays in the same situation.

Some may be infuriated by why a woman stays with her abuser, but Alana is an excellent example of why the cycle of abuse is so complex.

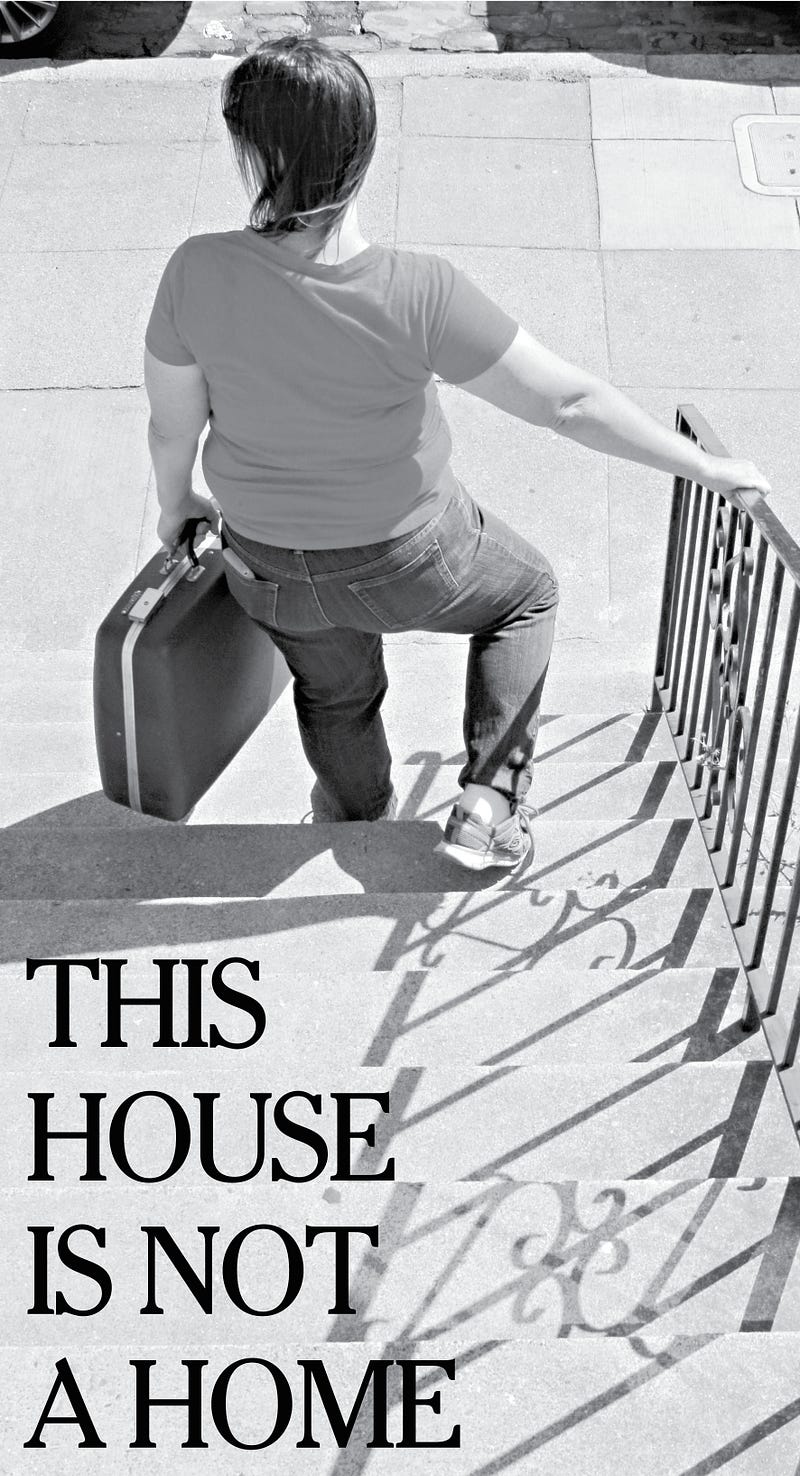

Without a set plan to leave, a women suffering abuse will stay at home because the fear of homelessness is real and overwhelming. Already, Alana has been held up at gunpoint twice while walking from a BART station to their downtown Oakland apartment, once for her phone, once for her purse. Their son was also robbed for his phone. The streets are terrifying.

Stressors that build up in a relationship and result in violence are often internalized. Violence against women is not unusual but is still a source of shame.

She stays because of the children. But Alana shows no sign of leaving, even though the children are no longer an issue. They are ready to be on their own.

Abuse is a matter of course — even embraced by society. A woman may internalize these attitudes toward abuse and thus the move here would include a hope that staying in the relationship would also mean an end to her suffering.

Once here, Alana went to her church. This is the first line of safety for many immigrant women. Churches offer networks of people who want to help. Most importantly, they are culturally sensitive.

The church she attends is Russian Orthodox, and people understand each other. Still, she hasn’t mentioned her husband’s behavior to anyone but this reporter.

In a new country there is little difference between leaving and staying; they are both equally fraught with danger.

I was her teacher when she first arrived, and we have a close and loving relationship. She trusts that I will say nothing about her life to anyone, and I will honor that bond between us.

In a new country there is little difference between leaving and staying; they are both equally fraught with danger. If the abuser senses that the partner might leave, and he fears police intervention because of the behavior witnessed in the home country, he will use his power to manipulate along with threats to keep her hopeless. Once she has tried and failed, not finding a suitable place to live, an immigrant woman would be hard pressed to make it on her own.

As in any country, couples stay together “for the children.” In many cases, this might mean intervention so severe as to have the children taken away by Child Protective Services.

The woman also often fears that moving out would traumatize their children even further. Very seldom does the woman consider that witnessing the parents’ combative relationship traumatizes the child.

Alana is still dependent on her abusive partner. Her $16 an-hour job doesn’t begin to pay for first and last month’s rent plus security deposit. Often an immigrant woman may depend on her abuser for her standing as an American citizen or to prevent her deportation. That is always a fear.

The imbalance of power in a relationship leaves an abused person open for manipulation and controlling by her partner, so moving out just doesn’t present is in itself not an option. Many immigrant women have to take into consideration their support system and the shelter she will need if she moves out.

Our culture doesn’t believe survivors. Survivors often do not find support within their group of friends or family, let alone the justice system when they attempt to protect themselves legally. When police answer domestic violence calls, (as I’ve urged Alana to do), they often ask the abused — in front of the husband and children — whether they’ve been hurt. Emotional abuse isn’t seriously considered in court.

A visit to a shelter is often a step back after finally breaking through the barriers that finally brought them to this country.

Often the abuser will find support in the social and legal system. The stigma in their own community is often greater for immigrants. Their community does not often have enough room for another person in their already crowded homes and apartments. And in Oakland, the problem is increasing as families are forced out due to rapidly rising rents.

Last, but not least, a woman who’s being abused may still love her abusive partner. Alana has often told me that she still loves him, even after I’ve done a body scan to detect any blows. Violence often starts after love has crystallized in the relationship. Love is an intense emotional bond, not easily broken. Even after being abused, Alana still loves and trusts her husband.

Abused women coming to this country have little recourse.

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) is not often available as a chance for renewal for women. After much vetting and approximately a two-year waiting list, the federal government will refer a woman to the IRC, and give her $1,000 to start a new life. The volunteer interviewed did not want to be named, but said that they are frustrated because the money does not begin to cover costs needed to help a woman reestablish herself.

The Family Justice Center has many rules and regulations, including extensive vetting. For people who are traumatized, it is almost like becoming re-traumatized. They are most often told “No, no, no,” even after breaking through the shame to the other side and asking for help.

Shelters are not an option for most women seeking homes. A visit to a shelter is often a step back after finally breaking through the barriers that finally brought them to this country.

Building Opportunities for Self-Sufficiency (BOSS) in Berkeley offers help with housing with Affordable Housing listings from the California Department of Housing and Community Development and HUD’s Affordable Apartment Search, but the waiting list can be up to two years.