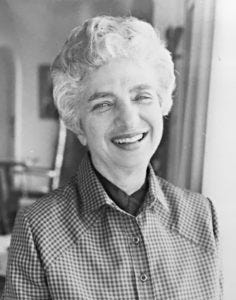

March 18, 1920 — Aug 26, 2016

Gilda Feller, a remarkable figure on the Berkeley political stage, gifted raconteur and beloved friend and family member, passed away after a brief illness on August 26.

Gilda served two terms on the Berkeley City Council from May 1977 to November 1984. Prior to that she was President of the Berkeley Albany League of Women Voters.

With her keen ear for humorous detail, she was the go-to source for journalists seeking quotes on political stories. She marveled that with all the serious issues at hand the most frequent request from callers around the nation was for updates on the Naked Man story.

Gilda handled her civic duties with gusto. During her tenure the city took a novel approach to cleaning up the red light district on lower University. Sex workers were left alone but their customers were ticketed. Civilians took down their license plates. Gilda walked the streets herself in the company of one or another of her teenage sons and wrote down license numbers.

Always gracious to her political foes as well as to her friends, she formed a special bond with Florence MacDonald, her counterpart on the opposition ticket. Florence was the mother of Country Joe, of Country Joe and the Fish.

Gilda also had a son named Joe. She loved to tell how Florence leaned over the council table one day and asked if Gilda had also named her son Joe after Joseph Stalin.

Gilda got a special kick out of this story because she had spent an unhappy year in Soviet Russia as a child. Her mother, Clara, had been part of the revolutionary effort against the Czar, and as a sixteen-year-old had smuggled dynamite under her skirts from Finland.

Full of nostalgia for her youthful exploits, Clara thought that Russia under Stalin would be a workers’ paradise. Seven-year-old Gilda and her older sister were packed off to Russia, where they were meant to settle, and confined to a farmhouse while Clara went out politicking.

After a year of this Clara was persuaded to return to the U.S. Gilda, who always said that stories improve with invention, told the story of what prompted their return in two ways. In one version it was her aunt, the highly placed Dora Lazurkina, who warned Clara that if she stayed any longer and talked any more she would get herself in trouble.

But in the other version it was Gilda herself who got through to her mother. They had gone to see Maurice Maeterlinck’s “The Blue Bird of Happiness.” At the end, after the brother and sister wander away from home seeking happiness only to realize that happiness is at home, Gilda leaned over and whispered in Clara’s ear: “That’s just like us.”

And shortly after that they packed up and returned to Boston.

Gilda was modest about her triumphs. She lived at home and commuted to the local college, but she never mentioned that the local college was Radcliff.

And she was matter-of-fact about her misfortunes.

Toward the end of her life she used to say, “I’m past my shelf-life.”

No one else thought so.

Gilda read all day and exchanged books and articles with kindred spirits.

She discussed politics with whoever dropped by to chat, always savoring the most ridiculous details and eager to hear more.

She will be greatly missed.

Gilda is survived by her sons Fred, Dan and Jon Feller, granddaughters Rebecca, Sophie and Daisy Feller, her daughters-in-law Alice, Claudia and Mercy Feller, and her grandson-in-law Jeremy Cunningham.

A memorial will be held on Sept. 18, 2016 at 11:00 a.m, in the Brazilian Room in Tilden Park.