But is it making the choices that will be to your benefit?

by Thayer Robins

Your brain is constantly “remodeling” itself, making choices about who you are and what you’ll be capable of. To influence these choices, it helps to understand a core principle of brain management: efficiency. My last column mentioned one expression of brain efficiency : how the brain builds a neural pathway to execute one task, then reuses it wherever possible it to execute other tasks.

A key reason for this brain efficiency is to conserve resources. Maintaining a neural pathway in the brain is expensive, and your brain is already a resource hog, using over 25 percent of assimilated oxygen and nutrients, while supplying a mere 2 percent of your weight.

Building a dedicated neural pathway for every task and maintaining it indefinitely would mean more pathways, more neurons, more supporting tissues, and so on. All this additional tissue would not only consume more resources but also take up more space, requiring a bigger skull — one too heavy for our existing necks to bear.

To keep size and resource use within manageable limits, the brain employs “negative learning.” That simply means it shuts down pathways containing learning it believes you no longer need or are better off without. Some of this is beneficial: for example, pruning unneeded sensory input that makes it more difficult to complete a task. Where this works against us is when our brain erases learning we need to live a full life.

Often this happens because of choices we make, not with the intention of dumbing down our brain but simply because we never got the instruction manual. Here are a few examples:

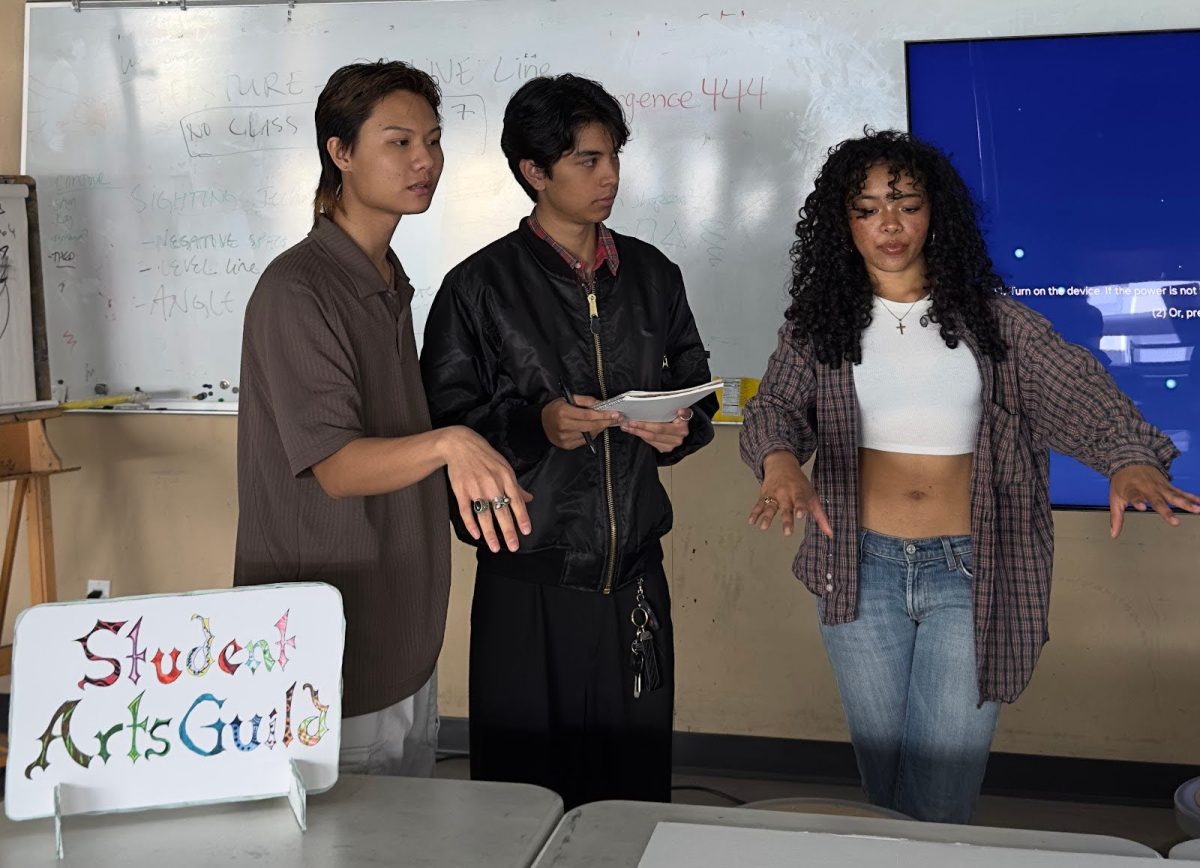

- Ari spends most of his day working on small screens. His brain decides to prioritize tight focus and reduce peripheral and distance vision.

- Tula doesn’t like straining to hear soft dialog in films and videos, so she turns up the volume or uses earbuds. Her brain shuts down pathways needed to hear lower volume and differentiate it from background noise.

- Mia decides that to avoid spraining her ankle again, she’ll walk cautiously and stick to sidewalks. Her brain limits her balance function to what’s needed for smooth level surfaces.

Our brain is designed to accommodate the choices we make. Through our choices, we can communicate our wishes and get the brain revved up for learning.

The clearest guidelines I’ve found on doing so come from movement expert Anat Baniel. My next column will discuss what we’ve learned from her and others about how to supercharge your brain. For a preview, check her webpage on The Nine Essentials, or her pdf “The Nine Essentials of Neuromovement” or watch “Anat Baniel: The Nine Essentials.”

Thayer Robins is a Tower staff writer. You can reach her at bavx-at-daytree.net.