How to do intentionally what kids do instinctively

by Thayer Robins

A key goal of this column is to help eradicate an old, thoroughly disproven idea: that our brain stops changing by the time we reach adulthood. This idea has caused much harm — unintentional but real — as folks with treatable brain injury are told nothing can be done.

Yet it’s not hard to understand how this idea took hold. After all, there are obvious differences between the brain of a growing child and that of an adult — especially when it comes to learning.

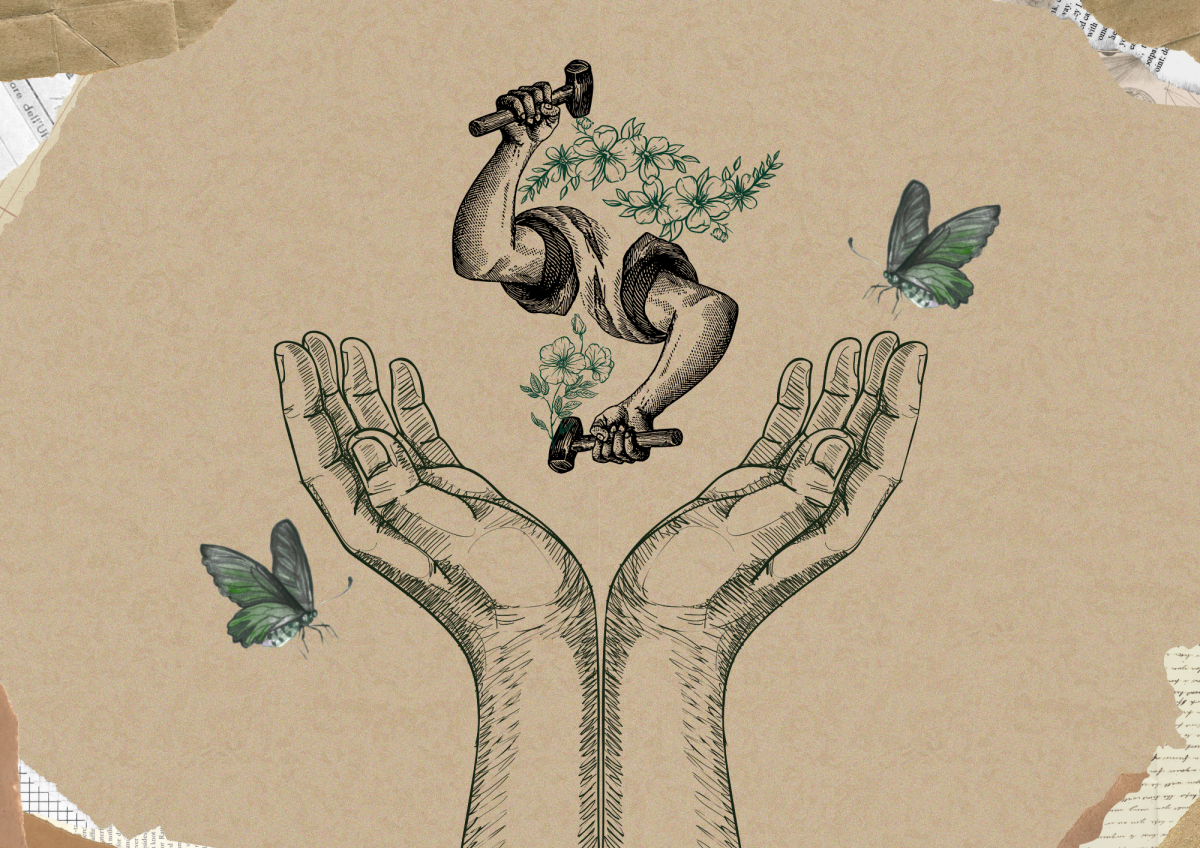

Kids are born with brains in full-on learning mode. The world surrounding them is brand new, and they eagerly absorb it all. They stare, listen, touch, taste — exploring and experimenting constantly — always pushing the boundaries of what they and their world can do.

And while they’re busy moving and testing and sensing, their brains are collecting data and using this data to build increasingly complex neural networks.

It’s not that adults can’t learn like kids learn. We can. But we have to know how.

As we grow in knowledge and competence, our brains turn from absorbing knowledge to knowing, and from playful, all-consuming exploration to the mindless replay of learned skills.

It’s not that adults can’t learn like kids learn. We can. The difference is that the mechanisms that turn kids into little learning machines are not triggered automatically in adults. We can turn them on, but we have to know how.

To that end, here’s my quick guide to creating a learning-friendly brain.

Step #1: Put your brain in learning mode.

To understand learning mode, it helps to look first at its opposite. To shut down learning, simply decide that what you already know is enough. This tells your brain you want it to rerun existing pathways and not create new ones. Always aiming to please, your brain will oblige, and learning will stop.

We’ve all done this at one time or another — effectively closed our minds to something new. The good news is, we never lose the ability to turn learning back on. To do so, we must seek out and embrace new knowledge, new ideas, new sensations, new experiences. The more we engage with what’s new and surprising, the more we excite our brains and get them ready and eager to learn.

Step #2: Tell your brain what you want it to learn.

The key here is intent. When we start a learning task by stating precisely what we want to achieve, our brain prepares the necessary pathways, making them ready to receive and process incoming data.

Step #3: Give your brain good data.

Everything that comes in through your senses, or is created by the mind through imagination, is raw data for your brain, and the quality of that data really matters.

“Garbage in, garbage out” applies here. When you give your brain data that are fuzzy, confused, or unimportant (because you don’t seem to care), you frustrate your brain and virtually guarantee a disappointing result.

Speed also matters. When you do something fast, your brain only has time to do what it already knows.

Sending your brain good data means setting an appropriate pace and focusing your attention.

Your brain likes detail, variety, and especially, differences. The more you slow down and pay attention — perceiving with as many senses as possible — the clearer and richer the data and the more your brain can accomplish.

Step #4: Hit the ‘save’ button.

How does your brain know what to save and what to toss? Pleasure. When we are pleased with an accomplishment, the brain calls it a success and makes it repeatable.

In fact, the brain learns best through a series of small successes, with each building on the next. You can set big ambitious goals. But to maximize success, you must tackle goals in small, achievable steps, and pat yourself on the back as each step is mastered.

The above offers a brief introduction and overview to a rich and exciting opportunity. To learn more, see books by Anat Baniel (Move Into Life, Kids Beyond Limits) and Michael Merzenich (Soft-Wired), or check out these free, online resources:

- Anat Baniel is a protogee of movement-pioneer Moshe Feldenkrais. She has done more than anyone I know to illuminate how we can stimulate our brains to learn. She describes her approach on her website, in the PDF The Nine Essentials of NeuroMovement, and in this video: Anat Baniel – The Nine Essentials.

- Michael Merzenich is a San-Francisco-based neuroscientist whose groundbreaking work has caused some to call him the “father of neuroplasticity.” Many of his TedTalks and other lectures for the general public are available on youtube, including his talk, How Kids Learn.

- Marisa Peer is a British psychotherapist who uses brain science to help her clients transform their lives. To hear her speak about her work, watch her TedxTalk To reach beyond your limits by training your mind.

- Josh Kaufman is an author who figured out how to learn a new skill in 20 hours. Find out how he did it in How to Learn Anything … Fast.

Thayer Robins is a Tower staff writer.