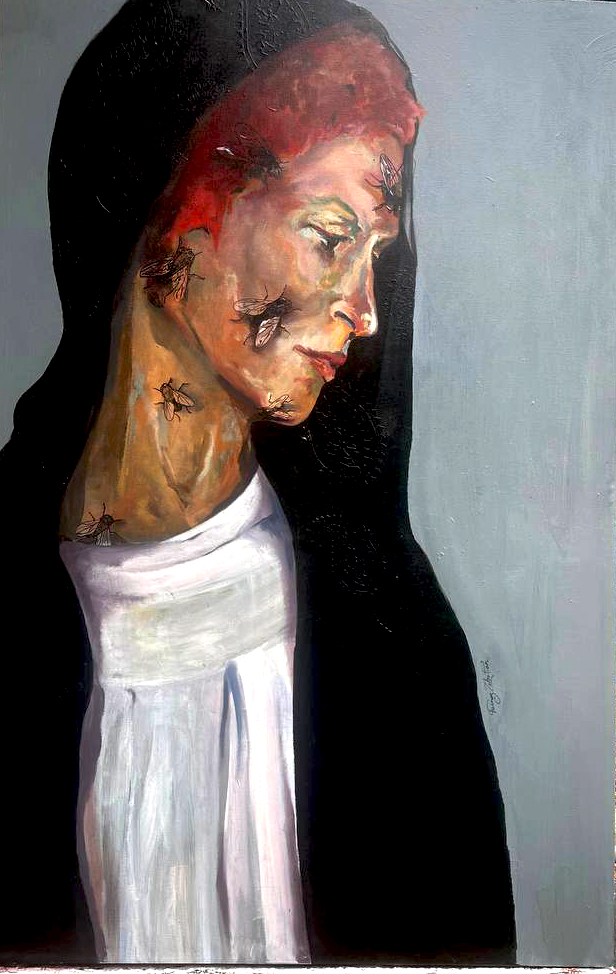

Correction 4/20/2023: The original version of this article misattributed an art piece by Farnaz Zabetian to Nazanin Parviz. The error has since been rectified.

Hair, an art exhibit curated by Iranian-American artist Farnaz Zabetian, held its closing reception at Laney College’s Jane Steingart Gallery on April 5, 2023. Hair addresses the issues facing women in Iran.

Along with Zabetian, featured artists Nasib Elahimehr, Maryam Farahzadi, Sora Kheiry, Nazanin Parviz, Maggie Parvaneh and Golnaz Shahmirzadi came together in solidarity with women in Iran who are protesting the death Mahsa Amini, a young woman who was detained by the Iranian Guidance Patrol – commonly called the “morality police” – who enforce compulsory hijab in public for Iranian women.

Hijab refers to the act of covering the head with a headscarf or other veil-like garment common among women in Islamic societies. It also refers to the garments themselves.

June Steingart Gallery at Laney College is directed by Robert Abrams, a faculty member of the Laney College Art Department. Abrams also owns Abrams Claghorn Gallery in Albany, CA, where he had previously featured some of Zabetian’s art, before inviting her to curate Hair.

The exhibit was originally organized to coincide with Women’s History Month in March, but the reception was pushed back to accommodate Laney’s Spring Break. The art pieces from this exhibit are available for purchase on the Abrams Claghorn Gallery site.

The reception opened with music by Rosa Los Santos and Peta Robles. Refreshments and pastries were provided through the Laney College Culinary Arts department. The reception was sponsored by the Laney Professional Development Committee.

At the conclusion of the reception, The Citizen interviewed Zabetian about her life and career, and the experience of curating Hair.

Featured Works

When choosing the featured artists in Hair, Zabetian was able to reach out to a tightly-knit network of Iranian artists based in the United States and Canada. Some of their featured works are described here.

Forbidden Beauty

Shahmirzadi’s work “Forbidden Beauty” consisted of color photographs of a fully covered woman set against a cold, gray foggy landscape. The blue of her garments suggests the color of the sky on a clear day, even as the model appears crouched down in cold water in one photo; in another, she stands tall in a wind gust that whips her garment like a flag, and covers the curves of her body almost like a burial shroud.

Severance

In a framed ceramic sculpture, “Severance,” Nazanin Parviz evokes the symbolism of women cutting their hair short in defiance of the way enforced hijab strips away women’s autonomy and their right to choose how they appear in public.

Goddesses

Nasib Elahimehr’s ceramic sculpture installation “Goddesses” consists of three jade-colored statuettes representing Woman, Life, and Freedom. It’s inspired by the current women’s protest movement taking place in her homeland.

Burning Hijab, Courage, Cutting Hair, Rebel Girl

Independent Filmmaker Maryam Farahzadi contributed a video piece, titled “Burning Hijab, Courage, Cutting Hair, Rebel Girl,” to the show. The video looped through several short animations of women. In one, a woman cuts her hair; in another, a woman is shot in one eye, but a rose blooms from the wound.

Utie

The Dallas-based Maggie Parvaneh featured two works. “Adrift,” a video presentation of the artist herself as a model, hooded and unveiled in a white bedsheet-like garment, functions like a screen on which video images of explosions and the violence of war are cast from an unseen projector. In the color photograph portrait, “Utie,” a nearly nude woman clad only in a black lingerie bottom sits on a garden planter-box, her back to the camera with her head turned to look over her shoulder. A small sliver of her bosom is exposed under her left arm, and a small shock of red hair curling out from under the black veil.

Interview with Hair curator Farnaz Zabetian

Zabetian, a 47-year-old Iranian-American who lives and works in Walnut Creek, began studying art at Honarestane Azadegan, a high school for the arts in Tehran. She attended the Tehran University of Art where she earned a Master’s in Fine Arts. At the age of 22, Zabetian had her first solo show, “Big Women in Little Frames,” an exhibition of 12 paintings at the Barg Gallery in Tehran in 1998. She has worked as an arts instructor at three universities in Iran.

After accepting an invitation to show her work in the United States, Zabetian decided to stay. She explained that if she had returned to Iran, she might face serious consequences.

She was assisted in getting settled in the United States by family members and the tightly-knit community of Iranian artists in America. Soon after she emigrated, Zabetian began exhibiting her work nationally, with shows in galleries and museums in New York, Los Angeles, and the Bay Area.

Zabetian had not considered herself a curator before Abrams invited her to curate Hair in conjunction with Women’s History Month in March. She said she accepted the invitation because she felt compelled to do something with other artists on behalf of women in her home country.

“In Iran, there is a revolution of women,” she explained. “Women are being blinded by pellet guns, being harassed in jail.”

Zabetian noted that Iranian men, too, are suffering for supporting women in their protests.

Zabetian told us she had three goals for curating the Steingart Gallery show. First, that people will understand the current problems and unrest in Iran through art. Second, to support the featured artists in their efforts to be commercially successful. And finally, to generate news about Iranian artists, and especially Iranian women artists.

Zabetian sees similarities between the extreme situation of women in Iran, and what she reads in local, national, and world news about the ways governments of all kinds try to control women.

“I’m worried for my daughter; I’m worried for all women.”

Zabetian spoke of her affinity for the “Me Too” movement’s ability to shine a light on harassment of women by powerful men, and how it speaks to her as an Iranian-American. She explained that in Iranian society, women that don’t cover their bodies are blamed for harassment.

“A woman has to think, ‘If I don’t cover, everyone will eat me!’”

When asked to describe her proudest moment as an artist, Zabetian recalled a moment from a 2017 show at the Peninsula Museum of Art in Burlingame (now located in San Bruno). She recalled that two women who attended the show’s reception approached her and discussed the emotions they felt from her piece, “Memory’s Fog.”

“The two American women said that the black veil, in particular, made them understand the struggles of Iranian women and the fact that marriage, in Iran, is sometimes similar to experiencing death.”

She confessed that her fear upon coming to the United States was that people outside Iran wouldn’t really understand or relate to her work.

“I felt so happy,” Zabetian said, as she recalled the conversation. “I didn’t know until then that my work was universal.”

Zabetian acknowledges that her art deals with very dark subjects – not always the kind of things people want displayed in their homes or personal spaces. When asked who the target market for her art is, Zabetian replied jokingly, “Intellectual people!”

She also explained that not all of what she creates is for sale – “Some are for me.”

She gestured to her right, where her oil-on-canvas portrait “Not Every Window Has a Beautiful View” was displayed on the Steingart gallery wall. The piece depicts a woman with outlines of large black house flies up her neck and across her face.

“I’m keeping this for my daughter.”

Not all of the work displayed in “Hair” contained the images of oppression conveyed by war, black flies, and fully covered women. Some of the paintings and video installations included beautiful renderings of monarch and mission blue butterflies scattered over women’s faces and bodies. We asked Zabetian what a butterfly symbolized to her.

“They are strong,” she explained. “A butterfly is born in one place, and flies in one direction to the place where it will die.”

“Like me,” she added.