In 1966, two Merritt College students, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, founded the Black Panther Party. It became one of the largest Black Liberation Movements in the United States. The Party’s far-reaching influence and 10-point program would play a major role in the Black liberation movement throughout the U.S., providing purpose, community, protection and resources to the oppressed.

With the sun sitting low in the sky, and his 10-year-old twins napping in the backseat, David Johnson sits parked at Merritt College, overlooking views of the Pacific Ocean and Golden Gate Bridge. As President of Merritt since 2020, he has been an avid supporter of preserving the Party’s legacy on campus.

Keeping his voice low so as to not wake his children, Johnson takes a moment to chat with me about his past and Merritt’s future.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

T: Where are your grandparents and parents from?

Johnson: My father was born in Austin, Texas where his parents, my paternal grandparents, are from as well, and he came to San Francisco right around when he was a teenager, so he experienced segregated schools and all that stuff. My grandfather was in the Navy, so he got stationed at Treasure Island. That’s what brought him out here during that period.

My mother was born at Fisk University Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee. My grandmother at the time was a student at Fisk and my grandfather was a student at Tennessee State, I believe.

T: What did your parents value growing up?

Johnson: Well, I’ll just start with education. Neither one of my parents actually went to college.

My grandmother, who was at Fisk, valued education. And then my father’s mother and father – education was very big with them. But my parents kind of grew up in the Cooley High period. Motown. So parties, and going to work right out of high school.

My father was very proud of the fact that he had a nicer car at 18 than my grandfather had. So he was making grown-up money at 18 with his ‘66 GTO and all that. But he definitely put an onus on hard work. My father probably worked 35 years at the post office, and actually, my mother worked for Peralta for a little bit. Just blue collar folk, and just kind of poured into me,“You need to go to school yourself.” They were big, “Don’t do as I do, do as I say” people.

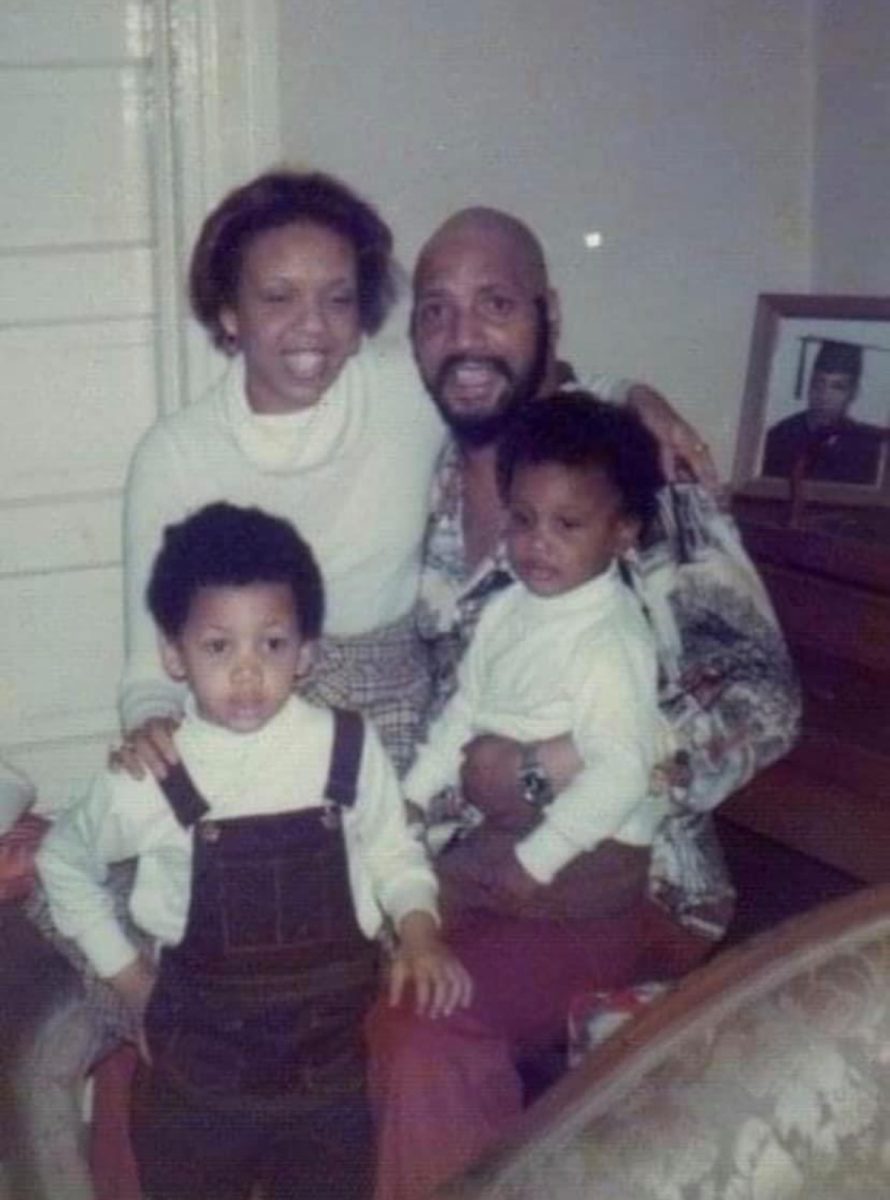

Gallery: David Johnson through the years

T: What’s a favorite childhood memory?

Johnson: Oh, wow. I would say from the time I was seven to the time I was maybe 14 my grandfather was a deacon at Third Baptist Church in San Francisco and every summer he would have these Baptist conventions. And they would always typically be on the East Coast, these national conventions.

Every summer, five of us would jump into a Caprice Classic, my grandparents, my younger brother, and me, and we would drive cross country. We would leave super early in the morning and then have breakfast in Reno, spend the first night in Salt Lake City, second night in North Platte, Nebraska, third night in Knoxville, Tennessee, and by the fourth day, make it to DC. And then on the way back, we would spend two weeks in Austin, Texas with my folks.

I got to see a lot of the country that way. That was a very good cultural experience in terms of some of the things that we got to see while we were on those trips, and then also being able to spend a little time in the South every summer on the way back.

T: I understand that you have a long history in Oakland. You mentioned that your mother worked at Peralta?

Johnson: My earliest memory of what a college even was [was that] my father knew somebody who had the keys to the gym at Merritt. And so on Saturdays, we would go up there and I might have been like four or five years old. And we would play basketball in the gym while I’d be on the side watching my dad.

My mother, when working for Kaiser and not being able to get a raise and watching people she trained surpass her because she didn’t have a piece of paper, part of her journey was, “Hey, I just need to get an [Associate’s Degree].” Her decision to do that and attend Merritt was a game changer for our family. She was able to move up professionally and do things for our family financially that we hadn’t been able to do before.

I learned how to drive at Merritt in the Merritt parking lot. Merritt is just very near and dear to me. I won’t tell you some of the other things we were doing in high school coming up to Merritt [chuckles].

I started off at Berkeley City College in terms of my journey in Peralta, but to have the opportunity to come to Merritt College as the Vice President of Instruction in January 2019 and become the permanent president in May of 2020. [That was] just full circle for me.

T: I heard you were possibly considering an HBCU satellite at Merritt. Could you speak a little bit on whether that is true?

Johnson: Just like colleges are HSIs, Hispanic-Serving Institutions, now the state legislature just passed legislation to create this [Black Serving Institution] designation. We’re really excited about that.

We also entered into an agreement with Sacramento State as part of what’s called the Black Honors College, which essentially says that if students maintain a certain GPA at Merritt and if they explicitly communicate and demonstrate a desire to be part of an authentic and genuine community that is going to put the accent and emphasis on a positive Black experience,then they can be guaranteed admission to Sacramento State into the Black Honors College, which is kind of like a school within a school.

T: In your educational career, you received a B.A. and Master’s degree in Communications. You eventually shifted to teaching African-American studies at BCC. What steered you in this new direction?

Johnson: At Howard [University], I was a communications major, and so I just kind of continued that when I got to [UC Berkeley]. I found that all of my projects at Cal, even though I was doing communications, always had something to do with African American history. Same thing at the University of Washington.

After working a couple of years as an Admissions Officer at the University of Washington, I said to myself, rather than just continuing to make forays into the field of African American history, why don’t I make a commitment to stay long enough to help cultivate that field? And so I applied to the history Ph.D. program. I got into Berkeley, which at the time was the number one history program in the country, and got to work with someone who I was actually talking about earlier today. His name was Leon Litwack, probably had the single greatest impact on me as an educator.

T: When you find the time, what are some things you enjoy? What are some of your hobbies?

Johnson: I watch a lot of sports. I mean, I don’t play as much as I used to, but sports would probably be my passion. I’m looking forward to the beginning of the basketball season particularly because now Gary Payton is coaching at College of Alameda.

And I listen to a lot of music and expose my twins to old school music. We’re listening to Cameo right now on the radio, trying to give them a sense of the culture and the music, just like my parents did me, with Motown.

T: As President of Merritt College, you recently changed the mascot from a thunderbird to a panther. What prompted you to change? And what does the panther mean to you? How have students responded to the change?

Johnson: We had been the Thunderbirds for several decades. That went back into the 50s and 60s. I found that many of our students didn’t know what our mascot was or didn’t really identify with it. I thought it was fitting given the legacy of Merritt College.

It’s funny that when I asked people who did not know what the mascot for Merritt College was, I said, “Well, what do you think it would be?” They just would automatically go, “Oh, it’s not the panther?”

The delicate dance I was trying to do was not appropriate the imagery. The strict imagery of the Black Panther that we all know, the iconic image of the kind of springing out, to not do that, but to still pay homage to our history and legacy. So far I think we’ve been able to do that. I think we needed a rebranding anyway. I was thinking of it like, as Jay-Z would say, “Allow us to reintroduce ourselves.” It’s been very, very positive.

I see people walking around campus rocking the shirts. Again, we were very intentional about the actual image that we did use to incorporate the school colors. I don’t know if you’ve been to our gym, but to see that panther in the middle of that floor, it’s been good.

T: Why do you believe the Black Panther Party legacy is one worth preserving?

Johnson: I think because in many ways it dramatizes the strength, the intelligence, the beauty of Black folk, what’s possible and the resiliency of facing what the party was taking on and trying to do. It foreshadows so much of what’s going on even 60 years later with the police brutality and all of that. To take that on and be able to effectively put into action this idea of revolutionary nationalism. To be able to achieve some of those things to some degree and even still be around despite some very deliberate efforts to neutralize them, and in some cases we’re talking about, you know, flat-out murder.

T: Where do you see yourself in five to ten years?

Johnson: Hopefully still President of a Merritt College that’s even better than we are right now. That has more resources. That has even deeper connections to the community.

We’re trying to really underscore this notion of not being just the college in your community but your community college. Trying to let folks know that even though we’re up on the hill, the college belongs to you too. I mean there are folks in the flats that don’t even know Merritt exists. It’s like come up here and get the education you deserve. You can look at those million dollar views from the parking lot just like everybody else can. This campus belongs to you.

So that would be my goal: to be presiding over a college that’s as vibrant and exciting, that goes back to being the intellectual and cultural locus like it used to be in the 60s. So if I could still be doing this 10 years from now but, just bigger and better.